Few phrases are more likely to discourage a gardener than “designated drainage easement.” Today’s trend toward building large homes on small lots, particularly in congested urban areas, has made that expression an all-too-familiar part of the homeowner’s lexicon. Large-scale grading and the construction of impervious surfaces like terraces, roofs, and driveways drastically alter the natural movement of water across a site. New neighborhoods must then be equipped with networks of catch basins, buried pipes, and open drainage swales that direct runoff away from homes. While these systems address hydrology issues, they create challenges when it comes to landscaping.

Fortunately, there is a solution. A dry streambed—one that has water running in it only in wet weather—can secure the soil and direct rainwater runoff while turning an eyesore into an appealing garden feature.

Common problem, creative solution

In 1993, Barbara and Gordon Robinson asked me to design the landscape for their new home. The site included a drainage area that collected surface water from several adjacent properties in a depression, or swale, across the rear property line, then directed it along the side of the house to a storm sewer at the street. On new homesites nearby, efficient concrete flumes had been constructed to carry the effluent as swiftly as possible. But Barbara, a dedicated gardener, was unwilling to sacrifice plants for plumbing.

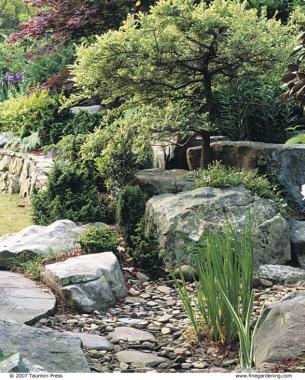

An initial plan to install a French drain buried beneath a pea-gravel path was discarded when the gravel rolled downstream in the first storm. I suggested a dry stream—a shallow swale lined with stone substantial enough to withstand a serious downpour. Large chunks of stone or concrete, termed rip-rap, are sometimes dumped on creek embankments to slow the speed of storm water and to prevent erosion. In a garden, the careful placement of water-worn stone, or river slicks, along a swale is more aesthetically pleasing and also provides an ideal place for plants.

Creating a dry stream that simulates a natural waterway is a job for a genuine craftsman, one who possesses the skill of an engineer and the eye of an artist. I suggested my clients meet with Rodney Clemons and Thomas Rice, whose work with stone in Japanese gardens and in naturalistic water features I had admired for years. After seeing the site, the team assured us they could construct an attractive and functional dry stream within the drainage easement, despite its rather narrow 10-foot average width.

The Robinsons’ builder had correctly set the grade of the site so that, with some fine-tuning by Rodney and Thomas, there was positive flow from a high point behind the residence to the street in front. Runoff is collected along the rear property line, in a shallow swale hidden in a buffer of densely planted evergreens. Wax myrtle (Myrica cerifera) and ‘Nellie R. Stevens’ holly (Ilex ‘Nellie R. Stevens’) are workhorse shrubs that screen this area effectively.

Before starting, Rodney and Thomas carefully laid out all the stone for the project on the adjacent vacant lot. They placed the first large boulders where the swale comes into view at the corner of the property. Then, like fitting together the pieces of an enormous puzzle, they positioned individual stones of various sizes and contours in a serpentine configuration along the side of the house.

Streambeds should meander naturally

Creating a gentle curve in a streambed results in a more natural appearance and serves to reduce the velocity of the water. Additionally, allowing the stream to meander creates areas for major plant groupings. Working with Rodney and Thomas as they placed the stone, I sited these planting areas at critical points: to soften the hard edge of the fence, to conceal Gordon’s outdoor grill, and to provide views from inside. Several groupings are anchored with slender river birches (Betula nigra) to provide overhead screening from a neighboring residence uphill. The trees also visually enclose this space, making this section of the dry stream a rather intimate waterway.

Varying the size of the stone adds drama in key locations. A group of large boulders creates an outcrop, perfect for showcasing special plants. Numerous small planting niches occur among other stones. One particularly dramatic boulder sits directly on the property line, and the bottom of the fence was recut to precisely follow the boulder’s contour. All of these devices effectively disguise the area’s original, corridorlike appearance.

The dry stream is located where there would ordinarily be a passage connecting the front and backyards. A subtle walkway was formed by placing flat stones in the center of the swale. Garden visitors can now safely navigate the dry stream in dry weather, and it is from here that Barbara tends her garden.

After a distance of about 75 feet, the fence along the property line turns to connect with the house. At this point, a gate (required to secure the backyard pool and contain family pets) intersects the dry stream. Rather than installing a solid, rectangular door that would interrupt the dry stream’s visual flow, we opted for a gate of slender vertical posts, curved along the bottom to mimic the profile of the rocks. It gives a tantalizing glimpse into the garden’s private space and marks the transition from dappled shade to full sun as the creekbed comes into public view for the first time. In heavy rains, water flows through the gate.

In front of the house, the dry stream follows the edge of the lawn. A huge planting bed rises along one side and extends to the property line. On this slope, evergreen Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica ‘Yoshino’) and several small shade trees interrupt a view of the adjacent house and provide a backdrop for a mixed border. At several locations, the plantings jump the stream, which helps visually link the lawn to the streamside garden. The result is that the dry stream passes in and out of view as it travels another 75 feet to the street. This disappearing aspect of the dry stream turned out to be critical as we applied, successfully, for approval of the design by the neighborhood homeowners’ association.

Plants secure the banks

With the waterway established, I selected plants to tie it visually into the larger landscape. I wanted the dry stream garden to be attractive year-round, especially that portion open to public view. I arranged trees, shrubs, and perennials in naturalistic layers and placed climbers and espaliered shrubs to soften the fence in the backyard.

Rather than limiting my plant options, the dry stream provides a whole range of growing conditions, depending on the availability of water and sunlight. Close to and actually within the swale is an ideal habitat for what I call “drip-dry” plants, which are tolerant of occasional inundation. These are species equipped with tenacious, rapidly growing root systems that anchor them when a large volume of water is channeled through the landscape. Conversely, the rocks above the water line provide conditions for species that prefer drier sites. Here are places for weeping woody specimens and perennials that trail over stone.

I selected small trees for their adaptability to flooding: river birch (Betula nigra ‘Heritage’), dwarf southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora ‘Little Gem’), and downy serviceberry (Amelanchier × grandiflora ‘Princess Diana’). Versatile native shrubs like anise tree (Illicium parviflorum), inkberry (Ilex glabra), summersweet (Clethra alnifolia), Virginia sweetspire (Itea virginica), and leatherwood (Cyrilla racemiflora) perform beautifully beneath the trees.

In the shaded backyard, Astilbe and Hosta cultivars, sweet flag (Acorus gramineus), and sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis) have established themselves in the swale. Above the rocks, where there is no danger they will float away, grow unusual gingers (Asarum spp.), coral bells (Heuchera spp.), foamflower (Tiarella cordifolia ‘Rambling Tapestry’), and Lenten rose (Helleborus orientalis). Decorative English ivy selections (Hedera helix cvs.), strawberry geranium (Saxifraga stolonlifera), and yellow creeping Jenny (Lysimachia nummularia ‘Aurea’) tumble over the stone and provide year-round interest. Several threadleaf Japanese maples (Acer palmatum var. dissectum) and a variegated Chinese elm (Ulmus parvifolia ‘Frosty’) perch above boulders like living sculpture.

Barbara and Gordon wanted the public portion of the dry-stream garden to be ornamental in all seasons. Here was an opportunity to indulge Barbara’s preference for bold, colorful plants. On the slope I staged such striking foliage specimens as Yucca × floribunda ‘Garland Gold’, Weigela florida ‘Variegata’, and burgundy-leaved barberry (Berberis thunbergii ‘Crimson Pygmy’). Several vertical blue-green conifers, including Sawara cypress (Chamaecyparis pisifera ‘Boulevard’) and juniper (Juniperus communis ‘Hibernica’), punctuate the bed. Sedum and Dianthus cultivars spread atop the rocks.

Perennials thriving close to the sunny streamside include yellow flag iris (Iris pseudacorus), daylilies (Hemerocallis cvs.), salt marsh mallow (Kosteletzkya virginica), cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis), and swamp hibiscus (Hibiscus coccineus).

Dry streams require only occasional maintenance—just the removal of debris that may become wedged among the rocks after a storm. If twigs and fallen leaves are allowed to accumulate they can interfere with the movement of water. A flexible leaf rake is a good tool for flicking plant debris away without disturbing the stonework.

A 150-foot dry stream might seem like an overwhelming element in a garden, especially when the water level rises to a foot or more in a typical rain. Once planted, however, it becomes a secondary feature. Then its importance lies in its ability to visually unite the diverse segments of a complex garden. Winding gently downhill, from shade into full sun, it creates a stunning setting for an ever-changing collection of plants.

The art and craft of laying a streambed

Photo/Illustration: Paula Refi

Photo/Illustration: Paula Refi

Photo/Illustration: Paula Refi

Your goal is a dry streambed that looks natural and timeless. Here are some tips for laying stone that have served us well.

Select a site for your dry streambed where the water will naturally run its course. Let your streambed meander. Curves slow down the water flow and help control erosion.

Choosing stones

Select stones that look natural in your region. Also think about the exposure: shady sites have mossy stones; sunny sites have bare or lichen-covered stones.

Allow the scale of the site to dictate the size of the stones. Small stones in a large, open space will look lost; likewise, huge boulders in a small space can be overbearing. Also, vary the size of your stones. You need a mix of boulders, medium-size stones, and river pebbles.

Create the effect of one large boulder by sandwiching several smaller ones together. Smaller rocks will be easier to move to your site and to manipulate into place. Because several smaller stones typically weigh less than a single large stone, you’ll also lower your cost, as stones are paid for by weight.

Moving and placing boulders

Hire out the heavy work. It’s quicker, easier, less costly, and a lot safer to move large boulders by machinery than by hand. You can supervise the placement.

Handpick any large boulders, avoiding those with large scrapes and nicks. Then make sure they are handled carefully. Chains and buckets on cranes or front-end loaders should be replaced with straps to avoid damaging the stones. (Lichen can take up to 100 years to grow 1 inch on a rock, so it’s nice to save features such as this.)

If you get a jagged chip on the exposed surface of a stone, you’ll need to chisel the stone smooth and touch up the spot with dirt, paint, or concrete stain. If you want to encourage moss growth on your stones, paint them with a concoction of buttermilk, cow manure, moss spores, and water.

Mimic nature. Use large boulders to signify a change in grade—the larger the grade change, the larger the boulder.

Avoid placing boulders in lines. Instead, place them in random groups of three to create an unequal triangle. The top silhouette is the most important; it should be soft and gentle, with no salient features, and it should taper to the ground.

Don’t stand rocks upright. In nature, they would lie on their sides or in a pile, or they would be partially buried. We bury up to two-thirds of a boulder, leaving the most attractive side exposed.

Place larger stones on the lower side of a bend in the streambed to help direct and slow down water flow. (In heavy rains, water will just run over the top of small stones when it reaches a bend.) You can also place a large rock in the center of your streambed; water will flow to either side of it.

Place boulders or large stones first, then gradually work your way down to the river gravel. In nature, the smaller stones tend to tumble downstream and into cracks and crevices. Use them this way in your dry streambed, too.

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

Pruning Simplified: A Step-by-Step Guide to 50 Popular Trees and Shrubs

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

A.M. Leonard Deluxe Soil Knife & Leather Sheath Combo

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Great ideas! I want to do a dry creek bed to separate a side driveway from the front yard.

Beautiful plants and design. I wish they would have said what the names of the colorful plants were in the main picture. The yellows and pinks and even the small blue one. This is why I wanted to read the article! Any help would be appreciated. I know the main one is a euphorbia.

Show a picture, name some of those plants. Not as interested in plant names that aren't shown.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in