Years ago I remember telling a landscape architect friend that I wanted to put together a talk about everything I’ve done wrong (in gardening rather than my personal life—that saga might be more of a novel). My friend was amused and said that nobody wanted to talk about, much less hear about, mistakes and failures. I don’t know if it was hubris or foolishness, but I went on to give classes and talks on exactly that subject. And people loved them.

My career in horticulture started when I was 19 and evolved into a landscape design practice. A cornerstone of that business is a 14-acre farm in Chester County, Pennsylvania, where my studio is located. This property has become an invaluable laboratory where my team and I experiment and study as naturalistic designers and horticulturists. Much of my growth and expertise has come from the sheer excitement of learning from failures and from the many years of watching our landscape design evolve. Establishing a garden based on an initial plan (perhaps one even scribbled on paper) is a great place to start, but as plants, the setting, conditions, our knowledge, and our tastes change, so should our designs.

Uncontrollable changes in a garden are inevitable and wonderful opportunities. During my three decades of experience, I’ve developed pain-saving design strategies and helpful pivots to get the greatest visual impact from a landscape over a long stretch of time. I hope you’ll be able to learn from my mistakes to achieve the garden of your dreams.

A high-impact—not high-maintenance—design

As this landscape extends farther away from the studio and out toward the natural meadow-like surroundings, the plantings become looser and less refined. They do not lose any visual impact, however, thanks to the plant choices and placement.

- Barn

- Entry drive garden

- Perennial gardens

- Terrace

- Farmhouse studio/office

- Front gardens

- Woodland garden

- Meadow gardens

1. Compose with plants of equally competitive natures

An important aspect of designing with plants is assessing their competitive nature in any given setting. Plants that spread freely and even aggressively through seed dispersal or another method can be very helpful in developing long-term resilience within a garden. But these sorts of species don’t come without challenges. Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum and cvs., Zones 3–9), orange coneflower (Rudbeckia fulgida, Zones 3–9), and baptisia (Baptisia spp. and cvs., Zones 5–8) are all long-lived, reliable performers that add impact to a design. They are also known to expand robustly and set plenty of seed in various types of soil. In order to get the visual punch I want but the balance every space needs, I have paired certain vigorous species with similarly competitive companions (photo above).

Learn more

Learn more

Get the planting plan

See which plants are used in this garden

Plants that go well together

Some of the author’s favorite plant pairings

I initially combined switchgrass with fairly competitive plants such as smooth aster (Aster laevis, Zones 4–8) and eastern bluestar (Amsonia tabernaemontana, Zones 3–9). In about four years the switchgrass had sown dozens of beefy seedlings that surrounded and engulfed the adjacent plants. A prairie fire can help keep switchgrass in check, but I’m not sure how your neighbors or the local fire department would respond. My neighbors responded with lawn chairs and a six-pack. If you’re not inclined to take on prescribed burns, you can pivot to a less aggressive cultivar of switchgrass such as ‘Shenandoah’. The tamer form, however, still makes for highly dynamic, long-lasting plantings (photo below). Be aware, however, that just when you’re feeling like you have perfected the balance between competitive plants, stressors (like wet springs that can rot seedlings) may leave you scratching your head.

Baptisia and orange coneflower (photo below), among several others, have been very successful at replicating themselves and are wonderful, high-impact plants that go the distance—in the right context. I began my career by using these highly competitive plants in mass plantings to create more with less. They push and pull against each other, as seasonal stressors affect them differently.

2. Work with the site challenges, not against them

It’s not only the plants that present challenges to a high-impact design; the site itself can pose a significant challenge. When I begin any garden design, I always consider the local pressures. Things like wind exposure, water-flow issues, deer and rabbit browsing, or poor soil structure can have negative impacts over time—even on the most expertly designed garden. It’s best to try and mitigate these potential problems in advance of planting.

For instance, in one of our landscape projects we noticed that an array of invasive plants had infiltrated the topsoil we were meant to shape into a garden. In addition, a penetrometer showed that the site consisted of heavily compacted soil. Could we have simply forged ahead and executed our planting plan? Yes, but that would have created a nightmare maintenance scenario down the road. Instead, we took the time to properly work and amend the soil, installed some larger woody plants (to penetrate the hard-packed soil), and capped the beds with shredded bark. We purposefully irrigated the borders to force the dormant weed seeds to germinate; the resulting seedlings were easy to remove because we weren’t working around 20,000 perennials that had been installed prematurely.

We had intended to start this planting months earlier and were forced to maintain a large number of plants in our nursery while we waited for the site to be ready. Slowing down the project didn’t create a perfectly sterile setting, but it did help us create a much more ideal environment to begin a new garden. Identifying potential pressure like this before planting and then developing a program to prevent or reduce future pressure can make a huge contribution toward creating a successful garden that looks great for many years.

3. Embrace changes, reassess needs, and pivot

If you want a dynamic, multiseason garden, you will need to make savvy decisions about editing, which is one of the more difficult lessons I’ve had to learn and teach. All too often I’ve come upon gardeners horrified by the ruthlessness that is sometimes necessary for eradicating what appear to be perfectly beautiful plants. But if your goal is high impact over the long haul, you must edit to keep things in balance.

A good example of this in my own garden is where I intermingled ‘Firetail’ mountain fleece (Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Firetail’, Zones 4–7) and wild bee balm (Monarda fistulosa, Zones 3–9) with coastal plain Joe Pye weed (Eupatorium dubium, Zones 3–9). It proved to be a stunning combination. Within three years, though, the wild bee balm and massive clumps of Joe Pye weed were seeding into all parts of the garden. ‘Phantom’ Joe Pye weed (E. maculatum ‘Phantom’, Zones 3–9) and ‘Purple Rooster’ bee balm (M. didyma ‘Purple Rooster’, Zones 4–9) proved to be much less aggressive. The bee balm does spread into heavy clumps, however, so I’ve had to reduce these plants every few years by either clipping back part of the mass or digging out an entire section to open views between the plantings. I tend to be overworked and don’t like to dig large sections out of the garden, but in a few seconds I can reduce the diameter of these clumps from 4 feet to 2 feet with just a small pair of clippers.

The undesirable aspects of this planting gave way to joy and exploration. It didn’t require a wholesale change, nor could it even be classified as a failure. It simply presented a chance to be in the garden, explore new approaches, and edit. Change happens every day, in life and in our gardens. But by embracing certain strategies at the start and being willing to pivot later, you can achieve a perfectly imperfect, high-impact design.

You May Also Like:

- Survival strategies – How to use plant competition to your advantage

- Work with your site – See plants that are easy to grow in challenging conditions

Donald Pell is an award-winning landscape designer in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania.

Photos, except where noted: courtesy of Donald Pell

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

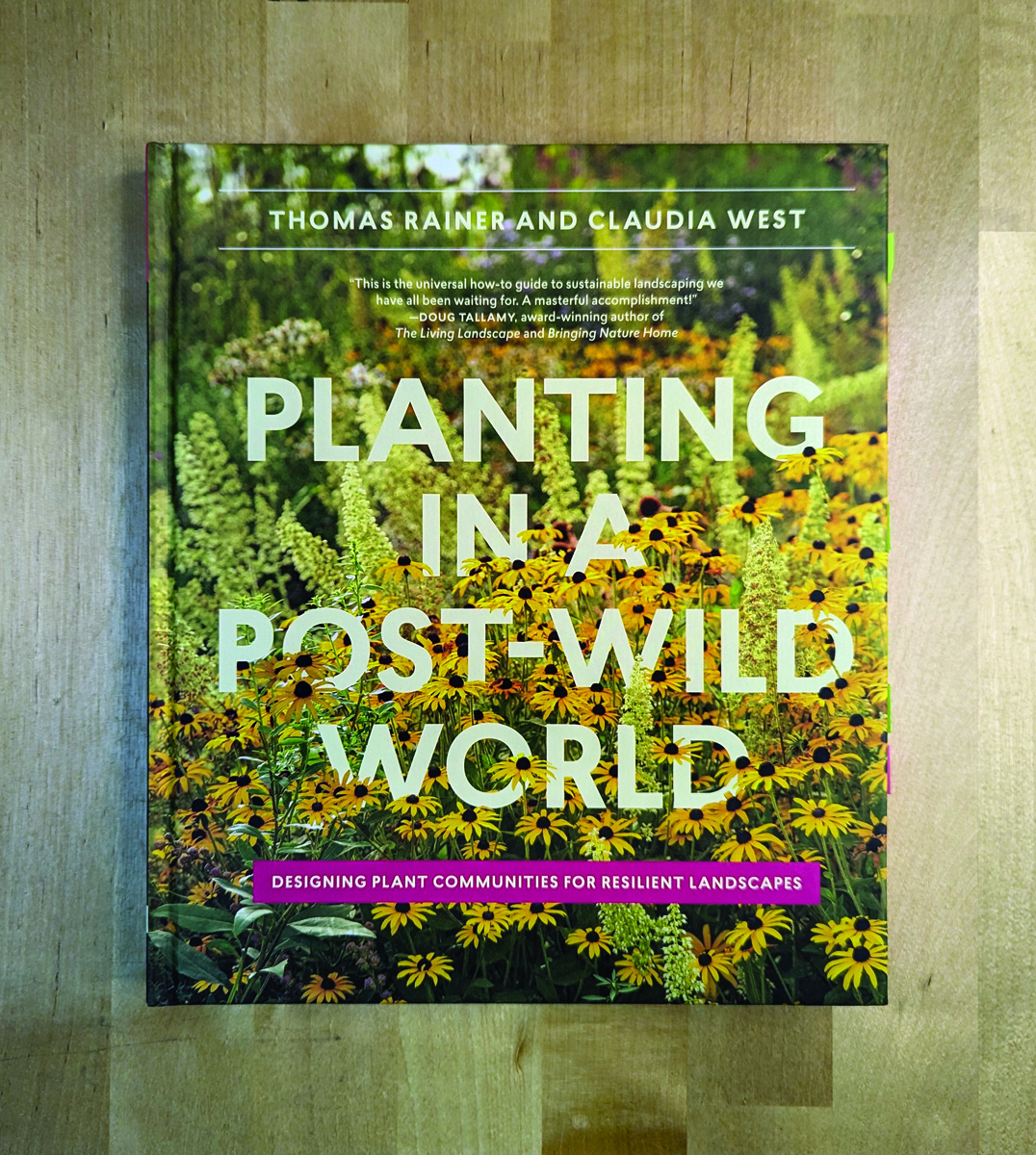

Planting in a Post-Wild World: Designing Plant Communities for Resilient Landscapes

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

ARS Telescoping Long Reach Pruner

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in