While an array of plants provide nectar for bees, butterflies, and other beneficial insects, some pollinators require individual host plants to develop from their larval to adult stage. As few experiments have looked into the effectiveness of cultivars as host plants, the straight species are generally preferred. A few of these plants are listed below. See more about whether nativars are OK.

Learn more: Episode 173: Beneficial Host Plants for Pollinators

Milkweed

(Asclepias spp., Zones 2–11)

Famed for their relationship to monarch butterflies, a wide variety of species can serve as sufficient larval host plants for this poster butterfly of national habitat conservation efforts. Take care to select plants with known native provenance to your region. Nonnative tropical milkweed (A. curvassica), in particular, is known to present challenges to monarchs by harboring a potentially deadly protozoan pathogen that results in deformed wings to emerging butterflies. This parasite is reported to be an issue in areas where tropical milkweed does not die back from winter cold. Various milkweed species are reported as present in nearly every county in the United States, and milkweeds are found throughout the Canadian provinces and states of Mexico as well. As host plants, they provide the fuel for the great migration to Mexico’s Sierra Madre oyamel fir forests, and to California’s Monterey pine, Monterey cypress, and eucalyptus groves each winter.

Willow

(Salix spp., Zones 2–12)

There is perhaps no more useful garden plant to wildlife than the lowly but mighty willow. According to my entomologist mentor Doug Tallamy, willows support the third-highest diversity of lepidopteran caterpillars of any plant, with at least 455 species using it as a host plant. Also, willows supply nectar-rich flowers adored by bees and other wildlife.

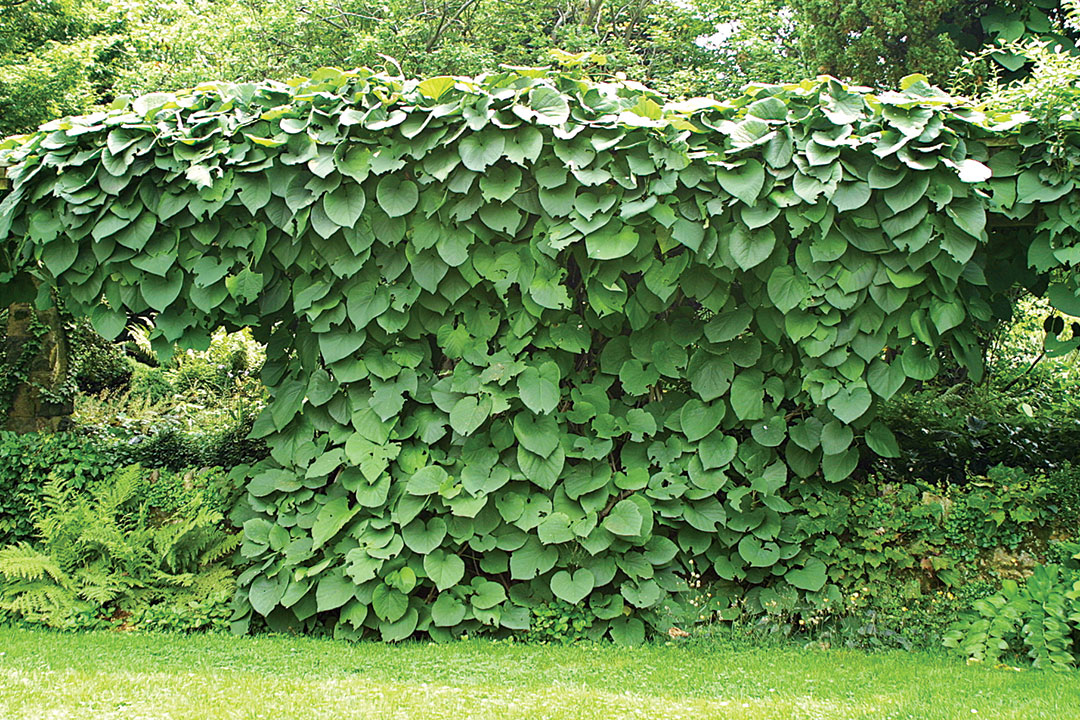

Pipevine

(Aristolochia spp., Zones 5–10)

Several butterfly species have developed a special relationship with pipevine plants, relying on them exclusively as host plants for rearing their caterpillars. The California pipevine swallowtail uses A. californica, while Dutchman’s pipe (A. macrophylla) serves as the larval host for the pipevine swallowtail. Pipevines contain toxins in their leaves that, when ingested by caterpillars, make them unpalatable to predators. Take care to select pipevines native to your region, as problems with butterflies involving nonnative tropical pipevines have been reported.

Pawpaw

(Asimina triloba, Zones 4–9)

The native range of zebra swallowtail butterflies overlaps with the native range of pawpaws from Florida up to southern Ontario, over to the eastern edge of the Great Plains. This is because their caterpillars feed exclusively on young leaves of pawpaw, which contain acetogenins, imparting protection from predators throughout their lifetimes.

Viburnum

(Viburnum spp., Zones 2–12)

Native viburnums are found from southern Florida to northern Maine, and across to the Pacific Northwest. Many serve as larval host plants for butterflies and moths, including arrowwood (V. dentatum), black haw (V. prunifolium), and possumhaw (V. nudum). More than 100 types of lepidopterans are known to feed on viburnum. In addition, the ripe berries are beloved by native birds, with at least 35 bird species devouring them to obtain energy before winter.

Wild buckwheat

(Eriogonum spp., Zones 3–10)

Wild buckwheats thrive in dry spaces from Mexico through Canada. This wide distribution is a wonderful feature, as many serve as host plants for various butterflies, moths, and skippers. Especially well loved by blue and hairstreak butterflies, buckwheats can be the scene of intense competition due to the diversity of species that utilize them for rearing their young. Try redflowered buckwheat (E. grande var. rubescens), ashy-leaved buckwheat (E. cinereum), or California buckwheat (E. fasciculatum) to start, as other species can be difficult to cultivate, even for experienced growers. As a bonus, wild buckwheat provides abundant, excellent nectar for native bees and wasps when in flower too.

Violets

(Viola spp., Zones 3–10)

Great spangled fritillary butterflies are a delight in summer, and their relative abundance is due to the widespread native range of their larval host plants: violets. Whether common blue violet (V. sororia), bird’s foot violet (V. pedata), or another native type, the butterflies lay their eggs near the base of these plants, which provide a ready food source for the young caterpillars. Common blue violets are ubiquitous in lawns throughout eastern North America, so perhaps we should all start seeing them as a helpful presence rather than a nuisance to dig/spray/eradicate.

Keith Nevison is the manager of the Center for Historic Plants at Monticello and the farm operations manager at the Thomas Jefferson Foundation.

This article originally appeared as a sidebar in Are Nativars OK? from Fine Gardening #192.

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

Pruning Simplified: A Step-by-Step Guide to 50 Popular Trees and Shrubs

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Monarch Butterfly Rescue Wildflower Seeds 4 oz.

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

The Nature of Oaks: The Rich Ecology of Our Most Essential Native Trees

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

It's so beautiful! Good information.

Wow! very nice.....it's amazing!

Thanks for sharing this information!

Thanks for giving Information.

Wonderful Article

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in