It took about five years and two road trips through England before Anne Campodonico was ready to start her garden. True, the Kentfield, California, mother of three wasn’t in a rush because she had her hands full chasing small children and renovating a 1930 chalet-style home that needed lots of work. But, as Anne tells it, she would satisfy her green thumb by reading a plethora of gardening books, watching the sun to study the yard’s exposure, and thoughtfully deciding what elements she’d eventually want in the landscape—and where she would put them. When the time finally came to stick her shovel into the ground, she was more than ready to create a unique garden style, one that had all the elegance of the English estates she saw in all those gardening books and magazines, but with the warmth of a family-friendly sanctuary. I sat down with her to find out how she was able to reconcile such divergent styles.

Did you set out to create a landscape of garden rooms?

Anne Campodonico: Yes, I did. I fell in love with English gardens early on and thought our house looked English in a way. I bought a number of coffee-table books on English gardens and kept telling my husband, Tony, “Don’t worry—it will save us a lot of money in the long run.” Mind you, we would not really begin to landscape for about five more years when I was making these purchases. After I had a vague idea of the elements I wanted in our garden, we decided to go to England to drive the countryside and visit some of those inspirational spots—Sissinghurst, first and foremost. I combed the grounds for ideas and left with the notion that its design ensured that there were always beautiful sights at every turn.

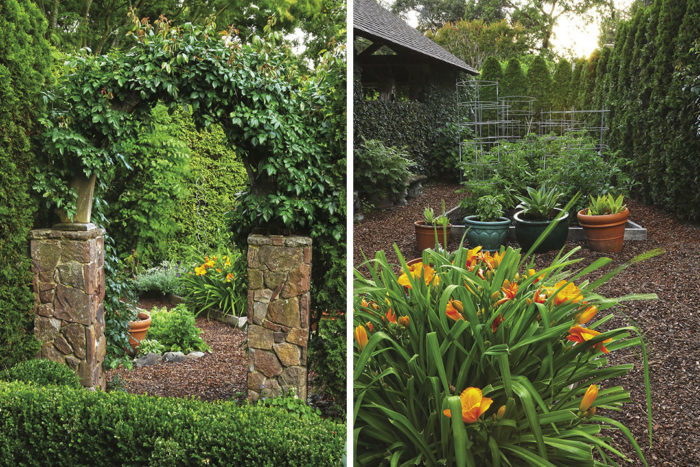

This became the main goal of my garden’s design. I have a relatively small area (when compared to an English estate). I didn’t want to limit myself, though, so I just made things smaller in scale. But much like those estate gardens, there is always a focal point to draw the eye, no matter where you stand. That makes things look bigger as you always have a reason to look beyond what’s right in front of you.

How did you choose what to use as dividers between the various areas of the garden?

AC: There are a couple of stone walls to give me a touch of England, but the rest I did with hedges, as they are easier to install and less costly.

Did you worry the garden would feel too formal with so many hedges?

AC: I wanted it to be formal. The irony was that in the rest of my life, I am not at all formal, nor with my children was I a strict disciplinarian. It’s laughable that I get so much pleasure of making the hedges so straight and perfect. It must be something subconscious.

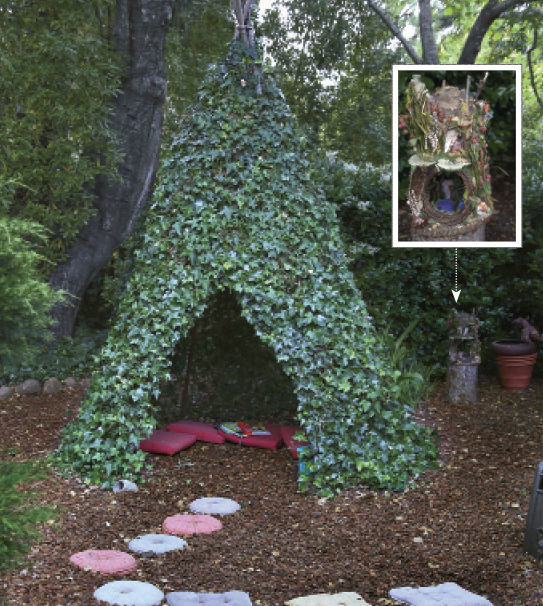

But even though my garden is formal, I think I have enough whimsy throughout to bring the formality down a notch. Take the area I created for my grandchildren—it has a tepee and fairy houses. My garden is—and always has been—a place for my friends and family to come and enjoy. So when the kids set up a volleyball court next to the perennial bed, I wasn’t a stickler. My choice of plants lends a note of informality, too. Yes, I have formal-feeling privets (Ligustrum spp. and cvs., USDA Hardiness Zones 3–10) and English laurels (Prunus laurocerasus, Zones 6–9), but I also have an array of less formal plants, like agapanthus (Agapanthus spp. and cvs., Zones 6–11) and ferns.

What do you consider the “bones” of your garden?

AC: We are lucky to have seven large oaks growing around the perimeter of the back lot, and they are the biggest backbone. Those and one small magnolia (Magnolia cv., Zones 3–9) are all that was salvageable on the property when we bought it. It was a rotten apple-tree orchard that had been severely neglected with 6-foot masses of brambles and poison oak. There was even cement poured down the hollows of the trees. I consider the oaks, the hedges, and the few stone walls the backbones because they are really the only things that are here for the long haul. The rest is ever-changing fluff, and that is where the fun comes in.

What was the biggest challenge of creating this garden?

AC: Communicating my visions to someone who would work well with me. Obviously, there were aspects of creating this landscape that required outside help. I hired a landscape architectural firm but was in tears after the meeting to view the schematics. They didn’t listen to me at all—it was their plan entirely! I then made a decision to use the architect who had done some remodeling on our house because he had done a great job of adhering to the house’s historical essence. I had the basic locations and elements of the landscape mapped out, but he helped with the layout, the elevations, irrigation, and hardscapes—leaving all the plants to me.

And that was the second-biggest challenge: At the time, I wasn’t a master gardener, and I really didn’t know much. My husband had a van then, so when it wasn’t filled with little leaguers, I would go out and visit every nursery I could to collect plants I liked. It was fun and a tremendous learning experience. It took me about two years to fill in the beds.

How did you manage to get so many plants into your foundation beds—which is very English in execution—without them seeming squished?

AC: Planting is my favorite part of gardening. I often plant too much knowing I’ll likely need to edit as the plants fill in. At that time, I can choose which I like the most, which ones don’t really work for me, or which ones need to be lovingly moved to another part of the garden. I have done many variations of plantings in this area. It’s not that I pull everything out and start over; it’s that I make small changes every year and after, say, five years, I’ll look back at photos I’ve taken, and the whole bed looks completely different. My garden is never stagnant because I feel that plants are like furniture—you can move them about until you find the perfect place, or you can give them away if you find you don’t like or need them anymore.

How do you balance the distinctly shaped shrubs/hedging with the more free-flowing shapes of the perennials?

AC: To achieve the proper visual balance, I’m always switching things up. I love a variety of shapes—whether it’s a plant’s form, flowers, or foliage—and I’m always thinking of that balance when I put one plant next to another. Often, my placement works until the plant gets bigger, and then I have to re-evaluate. It’s always an ongoing process. I took a class about 25 years ago on editing your garden—probably the most memorable class I’ve ever taken and the one I took most to heart.

Why did you enclose the veggie garden in a hedged room, and what effect does that have on the space once you’re inside?

AC: There is no reason for me to have a big vegetable garden. We have many wonderful farmers’ markets around here, and I can get all the great produce I need very easily. Besides, cooking is not another passion of mine. So I mostly concentrate on herbs and tomatoes, which I can never get enough of. I also have flowers for cutting in that area. Since the space is more utilitarian and much less formal than the rest of the garden, it seemed natural to section it off on its own. That room is my favorite space, however. It’s the place I go to get away from it all and be surrounded by beauty. And if I get hungry, I have plenty to eat!

Orange is not typically a hue associated with English gardens. What role does that color play in your space?

AC: There was a time when my garden was all pinks and purples, and then all of a sudden, I found myself planting only plants that bloomed yellow, red, or mostly orange. Not only the flowers but many bigger shrubs were replaced to reflect my new color scheme, too. I didn’t realize what was happening until I found I was doing the same color editing in my closet. I finally put two and two together: I had started having hot flashes, and unlike most women I know, I actually love the warmth. I was just expressing my pleasure at finally being warm. Besides, there are so many wonderful plants that bloom in varying shades of orange—it ended up being a blessing in disguise. Maybe not very English, but still a blessing.

Rules for Garden Separations

Although Anne and Tony Campodonico’s garden is divided into many various garden rooms, you never feel hemmed in or claustrophobic while walking through it. Here are a few tips on making sure that if you section off your space, it will still feel welcoming.

1. Use more than one material

Don’t rely only on hedges, stone walls, or wooden fences to section off parts of the garden—use them all. Installing an array of different materials adds interest and texture to the overall landscape and can help keep costs in check. When you’re mixing materials, try to make sure that no one material is much more prevalent than another in a given area. This helps keep the landscape feeling cohesive.

2. Don’t make all the “walls” 15 feet tall

Much like the various other plants in a garden, your hedges and/or walls don’t all have to be the same size. For instance, Anne kept the hedges along the walkways surrounding the house low, so you can see over them while moving through the space. In contrast, the hedges around the children’s play area are over 10 feet tall, creating a completely separate room with a magical secret-garden feel.

3. For instant maturity, rely on vines

Although perfect garden dividers, hedges take time to fill in and get tall. If you want quicker gratification, use a fast-growing vine, like creeping fig (Ficus pumila, Zones 9–11), on a fence or the side of a building to achieve a similar look.

Danielle Sherry is the senior editor.

Photos: Danielle Sherry

Illustration: Elara Tanguy

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

Chapin International 10509 Upside-Down Trigger Sprayer

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

A.M. Leonard Deluxe Soil Knife & Leather Sheath Combo

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in