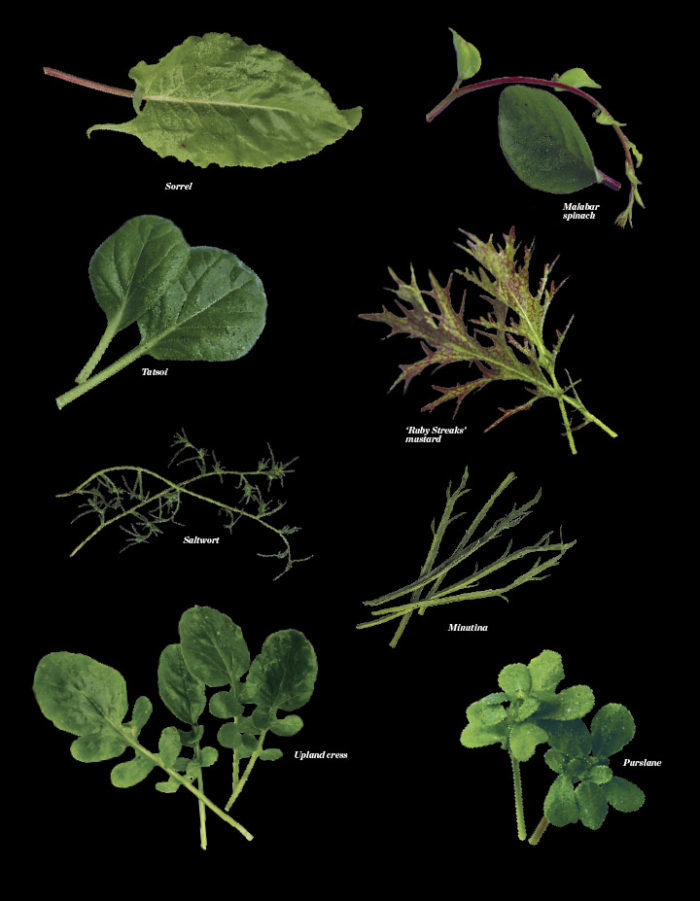

Beyond the Basic Greens

If your salad bowl just isn’t exciting enough, grow these unusual options

Fresh-picked salad greens are among the most rewarding vegetables that a gardener can grow. What else yields tasty baby leaves in just 30 days from a few seeds sown in a container or an empty corner in the garden? The salads of my youth were simple: lettuce, tomatoes, and maybe some cucumber slices or grated carrots. These days, seed catalogs offer a tasty, tantalizing cornucopia of new possibilities. There are heat-tolerant greens that produce through the “dog days of summer,” when temperatures soar above 90°F, and there are also cold-hardy varieties that bring diversity to the winter table. So you can look forward to eating fresh salad every day.

I still grow a variety of lettuces year-round in my garden, but it is the unusual greens that add the diversity in taste, color, and texture that I crave. If you are ready to explore new looks and tastes beyond lettuces, spinach, and arugula or if you want to have fresh greens for more days of the year, here are some extraordinary varieties to enliven your garden and your salad bowl.

Malabar spinach is a hot-weather stand-in for regular spinach

Name: Basella alba and B. rubra

Type: Warm season

How to grow it: This South Asian perennial vine is a heat-loving, frost-sensitive green that prefers full sun but will grow larger leaves in partial shade. Like most plants, Malabar spinach prefers rich soil, but it tolerates a range of conditions, including less-well-drained soils. Its vines start slowly but eventually need a sturdy trellis on which to grow. Harvest the young shiny leaves and shoot as needed.

How it tastes: The leaves and young shoots are popular in Asian, Indian, and African cuisines for use in soups, stir-fries, and curries. Here in North America, it’s usually grown as a replacement for regular spinach during the heat of mid- to late summer. It can be substituted for spinach in soups, curries, omelets, and soufflés. Be careful not to overcook it; if you do, you might find that your fresh greens become a mucilaginous mess. You can store the leaves for up to four days by keeping them refrigerated in a ziplock bag with a moist paper towel.

Tatsoi is mild tasting and easy to grow

Name: Brassica rapa (Narinosa group)

Type: All season

How to grow it: This is an easy-to-grow, cold-hardy member of the mustard family. Its spoon-shaped, shiny, dark green leaves grow in rosettes close to the ground in cool weather. If you keep a row cover on tatsoi, you can have greens all winter in USDA Hardiness Zones 6 and warmer. Or you can grow it in a cold frame or greenhouse in Zones 3 to 5. Succession-plant tatsoi from early spring through midfall. It bolts easily in hot weather, so you will only get baby leaves. Tatsoi can be grown in a range of soils, but it appreciates moisture, organic material, and nitrogen. Start your harvest with thinnings. Young plants are ready to eat in three to four weeks, while full-size plants take six to eight weeks.

How it tastes: Tatsoi’s mild, sweet taste and crisp stalks make it one of the most popular mustard salad greens. Its creamy texture and subtle yet distinct taste when cooked makes it taste closer to spinach than other mustards.

Upland cress is like watercress with an extra kick

Name: Barbarea verna

Type: Cool season

How to grow it: This biennial plant grows in rosettes of lobed, glossy, dark green leaves. It tolerates a wide range of soils—even heavy clay if the soil is well-drained—though it performs best in a slightly acidic soil that’s rich in organic matter. Shade upland cress during hot weather. Harvest it in fall through early spring, but stop harvesting once it flowers before the leaves turn tough and bitter.

How it tastes: Upland cress has a zesty, spicy, peppery flavor like watercress but a little stronger. It’s traditionally eaten as a cooked green, like spinach or kale, often with a bit of bacon or salt pork. It’s now commonly added to mixed salads and sandwiches in upscale restaurants for its shiny, dark green leaves and nutritional value. It’s full of antioxidants and high in lutein, vitamins A and C, iron, and calcium.

‘Ruby Streaks’ mustard adds a pretty, peppery element to salads

Name: Brassica juncea ‘Ruby Streaks’

Type: All season

How to grow it: This attractive plant looks good in both edible landscapes and containers. The leaves are, perhaps, the most beautiful of all the baby mustards: dark green to maroon, lacy, and finely serrated. Cold weather intensifies the purple color. The flavor of ‘Ruby Streaks’ is best when the plant is raised in rich, well-drained soil with a steady supply of moisture for brisk growth.

How it tastes: ‘Ruby Streaks’ mustard adds color, lift, and a pleasant mustard flavor to salad mixes. It has just the right kind of spiciness with a hint of wasabi. Sautéed or braised, the leaves taste mellow and blend with the flavor of butter or garlic, just like spinach, kale, and collards.

Purslane is a weed to fall in love with

Name: Portulaca oleracea ssp. sativa

Type: Warm season

How to grow it: This is a fast-growing annual succulent. The wild version is labeled a noxious weed in the West by the USDA, but it is considered a beneficial weed by some because its deep roots bring up water and nutrients for other plants. The cultivated variety is more upright than wild purslane. Harvest the tender young leaves and side shoots as needed. Pick in the early morning or in the evening to preserve the leaves’ juiciness. Purslane can be aggressive, so pinch it back often to prevent self-sowing.

How it tastes: As a succulent, purslane is crunchy with a mild, slightly sour, citrusy flavor. Besides salads, purslane can be used to thicken soups and stews because of its high level of pectin. Purslane is amazingly high in omega-3 fatty acids. It also offers lots of vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants.

Sorrel is a vigorous plant with piquant flavor

Name: Rumex acetosa

Type: All season

How to grow it: This cold-hardy plant gives us some of our earliest spring greens. Sorrel is a perennial, but many gardeners grow it as an annual because, after a few seasons, the plants look kind of tattered and (some say) the taste gets too acidic. Sorrel can be started from seed, root divisions, or transplants. Harvest side leaves until the plant is well established, then cut the whole plant right above the crown. Established sorrel plants can be divided in spring or fall; dividing plants keeps them from getting tough and developing a strong taste. For the best-quality summer leaves, grow sorrel in partial shade and keep the seed stalks cut back.

How it tastes: Sorrel has crisp stems and leaves with a tart, lemony flavor. It’s high in oxalic acid, so use it sparingly raw, mixed with other greens in salads, and more generously in soups and sauces. Because of the oxalic acid, your food will have better color if you avoid cooking in unlined aluminum or cast-iron pots.

Minutina is dainty and distinctive

Name: Plantago coronopus

Type: Cool season

How to grow it: This frost-hardy native to Eurasia and Africa has been grown in North America since Colonial times, when it was thought to be good medicine for fevers. It provides mild, tasty greens all winter, especially if you succession-plant from late summer to midfall. In most areas, it will overwinter if you provide a row cover, a cold frame, or an unheated greenhouse. Minutina germinates easily; the seedlings look like blades of grass. For the best quality and taste, especially in warm weather, succession-plant every two to four weeks.

How it tastes: Minutina is prized for its mild flavor and crunchy texture. Its narrow leaves grow in small rosettes and have distinctive horns on the ends as they mature, making this green a decorative salad addition. You can eat the flower buds, too. Minutina works well for cut-and-come-again harvesting if you don’t mind its slow regrowth.

Saltwort can be eaten raw or lightly cooked

Name: Salsola komarovii

Type: All season

How to grow it: There are different plants known as saltwort in various parts of the world. The one that I grow for greens is the Japanese type (okahijiki) with its succulent, seaweed-like green leaves. Saltwort is a marsh plant, so provides consistent moisture for germination and growth. I get the best results by watering every day until seedlings emerge. Hot-weather sowings can have spotty and slow germination. Harvest it young to avoid woody stems and prickly leaf tips.

How it tastes: Eat saltwort rolled up in sushi, added to salads, or served lightly steamed. It provides great texture and a subtle flavor. It doesn’t taste salty to me, but it might if it were fresh-picked from a salt marsh. It’s not often cooked in American kitchens, but it holds its crunchy texture, so it offers a good bed for fancy meat or fish dishes.

Greens for every season

Most greens are cool-weather plants that prefer the mild temperatures of spring and fall. But there are a few options that either revel in the heat or that can grow during both cool and warm seasons. Here is a breakdown of the three types of greens discussed in this article.

Cool-season greens

These greens, which include upland cress and minutina, can stand some frost and can extend the growing season through winter and into early spring—even as far north as Maine when protected from extreme cold. They are best started in late summer or early fall. These greens like warm soil for germination but grow best in cool temperatures; in cool regions, you can plant them in spring, as well. Cool-season greens are usually winter hardy unprotected in Zones 7 to 9; in colder areas, grow them under a row cover or in a cold frame.

Warm-season greens

When the thermometer hits 90°F, traditional lettuce, spinach, and kale turn bitter and bolt. But this is just when Malabar spinach and purslane are hitting their stride. These are heat-loving, frost-sensitive plants. Both need warm temperatures for germination, and they thrive in hot-summer weather. Transplant seedlings or direct-sow seeds in late spring to early summer when the soil is warm, or start either crop indoors six weeks before the last frost.

All-season greens

Most of these greens are actually cool-season plants that can be grown successfully through summer in most locations because they are slow to bolt (saltwort and sorrel) or can be harvested as tasty baby leaves with succession plantings (tatsoi and ‘Ruby Streaks’ mustard). Start saltwort and sorrel indoors in late winter to early spring, or direct-sow seed in late spring to early fall; direct-sow tatsoi and ‘Ruby Streaks’ mustard. Succession-plant from early spring to early fall. Use a row cover to control flea beetles in these and other mustards.

Ira Wallace is a co-owner of the Southern Exposure Seed Exchange in Mineral, Virginia, and the author of The Timber Press Guide to Vegetable Gardening in the Southeast.

Sources

The following mail-order seed sellers offer the widest selection of the greens featured:

• Fedco Seeds, Waterville, Maine; 207-426-9900; fedcoseeds.com

• Johnny’s Selected Seeds, Albion, Maine; 877-564-6697; johnnyseeds.com

• Southern Exposure Seed Exchange, Mineral, Va.; 540-894-9480; southernexposure.com

Photos, except where noted: Michelle Gervais, Carol Collins, Maxine Adcock/gapphotos.com, Maderibeyza/courtesy of commons.wikimedia.org, Victoria Firmston/gapphotos.com

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

Burpee Organic Coconut Coir Concentrated Seed Starting Mix, 16 Quart

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Gardener's Log Book from NYBG

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

A.M. Leonard Deluxe Soil Knife & Leather Sheath Combo

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in