Companion planting is the long-standing practice of partnering two or more plants in hopes of achieving a new benefit. Information on which plants to use in companion planting has been passed around among gardeners for generations, but those suggestions aren’t always based on sound science. We’ve all probably heard that “roses love garlic” or something similar. However, recent research from universities and agricultural facilities around the world is looking at companion planting in a new light. Many of these studies point toward a whole new way to companion plant—a way that approaches the garden as an ecosystem comprised of many different and complex layers of organisms, all of which are interconnected in a massive web of life.

Companion planting has other names

In the scientific community, you won’t often find the term “companion planting” being used, perhaps for fear of the long-standing folklore-oriented reputation of the practice. When looking over the many credible studies that explore mutualistic relationships among multiple plants in field studies, you’ll find terms such as the following being used instead.

- Polyculture. This is an agriculture system in which multiple plants are planted in the same space to mimic the diversity found in a natural ecosystem. Polycultures create stable environments where pests and diseases don’t spread as easily as they do in a monoculture.

- Intercropping. This is the practice of growing multiple crops in the same field area in order to encourage beneficial results, such as reducing disease, limiting pests, or improving soil.

- Interplanting. Essentially the small-scale equivalent of intercropping, interplanting involves the mixing of multiple types of plants in the same space in search of positive results.

All three of these practices involve combining multiple plants to achieve a positive result—which is, of course, the definition of companion planting. Regardless of which term is used, they all translate to the same thing: maximizing plant diversity in hopes of achieving one or more benefits. Companion planting is intercropping or interplanting but typically on the smaller scale of a home garden. And a polyculture is the result. Though in many ways we are only beginning to understand the complexities of these interactions, we can already use our current knowledge to become better gardeners and to build healthier, more productive gardens. Companion planting can provide many benefits; here are just a few of the most helpful ones

Benefit 1: Soil improvement

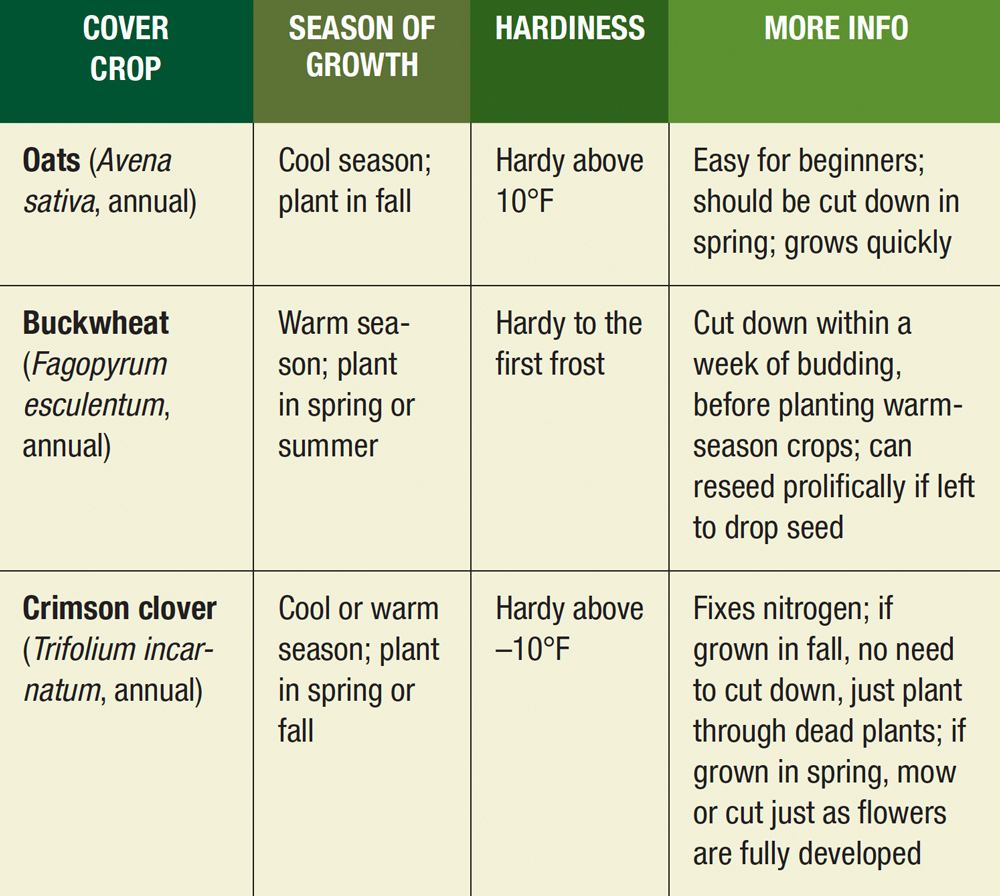

One way in which companion plants can be used to improve soil is through the use of cover crops. Typically, cover crops are annuals that are not harvested and are planted when the garden is fallow and devoid of harvestable crops. They can then be turned into the soil a few weeks before the bed is ready to be planted, or they can be mowed down and planted through. Using cover crops before or after growing your harvestable crop provides multiple benefits. They can aerate the soil, provide organic matter to decomposers, and allow nutrients to become available to the next round of veggies. Cover crops are not only useful to farmers; the benefits can be achieved even by home gardeners.

When to plant and cut down cover crops

The time to sow seed depends on the type of cover crop you’re planting. There are two main types.

- Cool-season cover crops are typically planted in the late summer or early fall, after your veggies have been harvested. They should be planted early enough to germinate and grow before winter but not to set seed. Some will survive the winter and then regrow in spring, while others will be killed by freezing temperatures.

- Warm-season cover crops are planted in spring or summer, either before a vegetable crop or in place of one in a fallow area.

|

|

Regardless of which type of cover crop you grow, timing the cut-down process is critical. Mow or cut down cover crops just after they come into flower. Leave the trimmings in the garden, where they can help block weed growth as they decompose. If you mow too early, the cover crop will regrow and try to bloom again. If you wait too late, the plant will set seed prolifically and become a nuisance. As with the rest of gardening, good timing is everything.

Benefit 2: Weed management

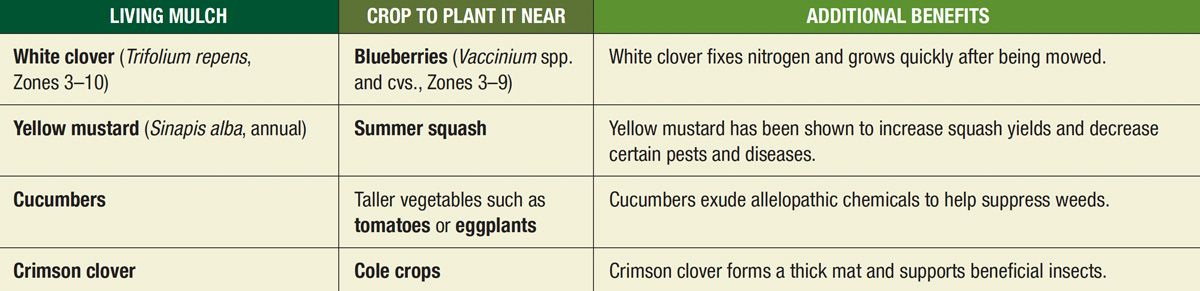

If you are looking for companion plants that help manage weeds, look no further than living mulches. Living mulches are low-growing companion plants that are planted beneath and around taller harvestable crops. Much like cover crops, living mulches aren’t planted to be harvested (though some of them can be); instead, they help crowd or shade out competing weeds around desired crops.

Use perennial living mulches around perennial vegetables or fruits, and annual living mulches around annual crops. If necessary, living mulches can be mowed down a few times throughout the season to keep their growth in check.

Keep in mind that living mulches can compete with desired plants for resources, so maintaining their growth definitely involves a careful balance. However, plants don’t live alone in nature; they live in tight quarters with many other plants, and that’s how it should be in the vegetable garden too. In some cases, companion plants actually help each other, rather than compete, in a process called resource sharing.

Here are a few great plant partnerships for weed management to get you started.

|

|

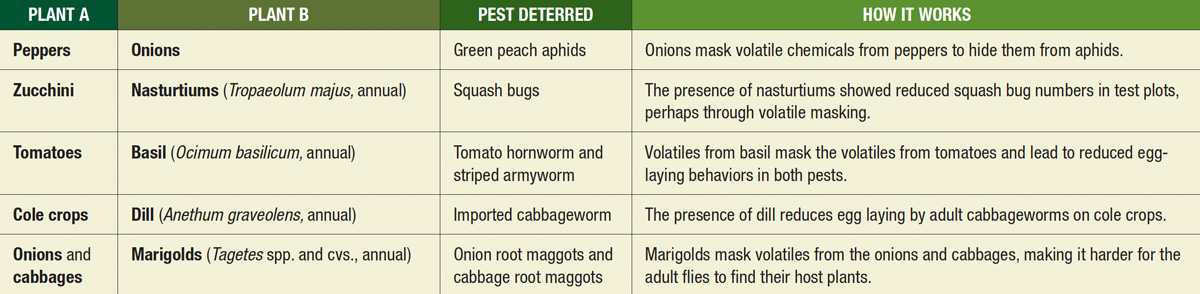

Benefit 3: Pest management

Pest management is one of the most popular goals of companion planting, and there are several ways in which it can work. Companion planting can disrupt insect feeding by masking or hiding volatile chemicals (chemicals that allow insects to recognize a plant) emitted by host plants. It can also interfere with pest egg-laying behaviors by masking host plants. And creating a general polyculture makes it more difficult for pests to find their host plants.

While a quick internet search will yield a tremendous number of lists of companion plants that supposedly perform one of these services, few of them are backed by research. Here are some that are.

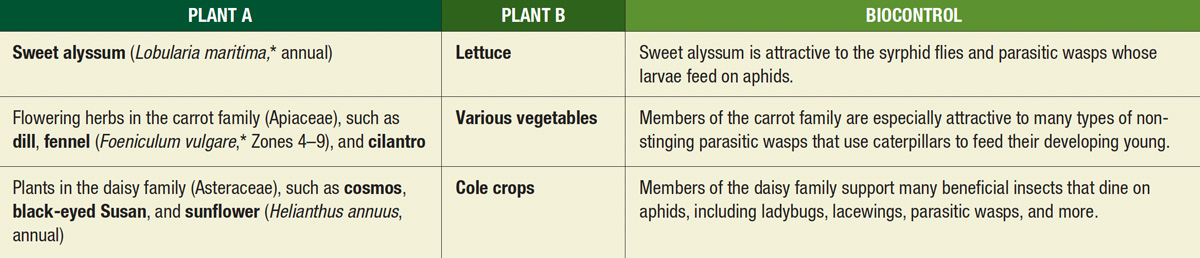

Benefit 4: Enhanced biological control

Biological control (or biocontrol) is the science of using one living organism to help control the population of another. Encouraging beneficial insects in your garden can prove very helpful in controlling pests. Beneficial insects provide natural pest control either by directly eating pest insects (predators) or by using those insects to house and feed their own developing young (parasitoids). They return an important balance back to the garden and reduce the need for pesticides and other pest-management strategies.

Most beneficial insects need three things to thrive: a pesticide-free habitat, the carbohydrates found in nectar, and prey insects to eat or lay eggs on. Companion planting can provide all three of these resources for beneficial insects, encouraging them to take up residence in your vegetable garden and do their good work. Here are a few companion plant partnerships to enhance biological control.

Find more Plants to Attract Beneficial Insects

*See invasive alert below

Benefit 5: Improved pollination

Companion planting can be used to enhance the pollination rates in your vegetable garden. Including a diversity of flowering plants in close proximity to your veggies will increase the number and diversity of pollinators, raising your chances of pollination success.

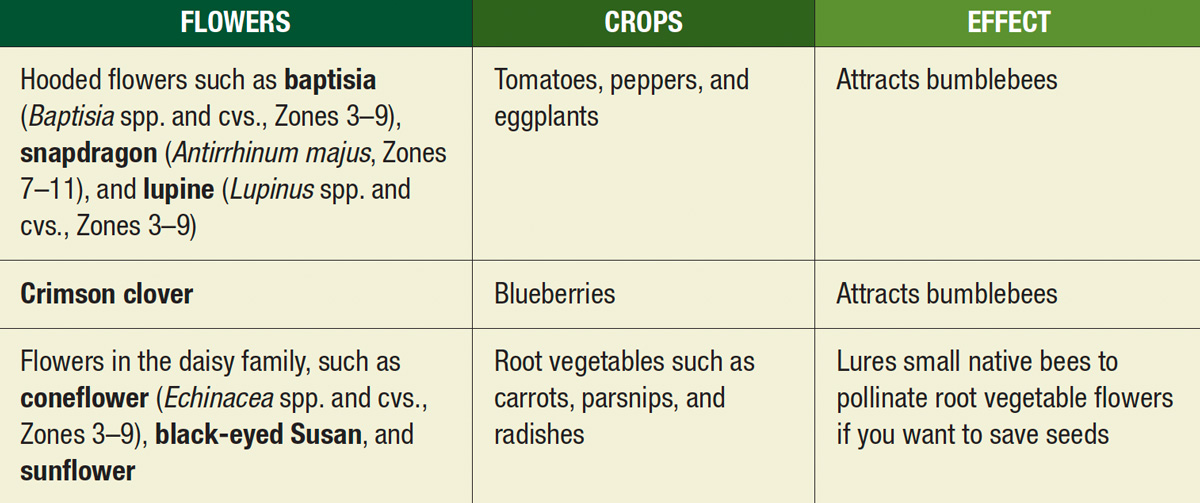

Plant these flowers and crops near each other to improve pollination.

*Invasive Alert:

Sweet fennel (Foeniculum vulgare)

This plant is considered invasive in CA, OR, WA, and WV.

Sweet alyssum (Lobularia maritima)

This plant is considered invasive in CA.

Please visit invasiveplantatlas.org for more information.

Jessica Walliser is a horticulturist, award-winning author of seven garden books, and a cofounder of SavvyGardening.com. For more information on companion planting, see her book Plant Partners: Science-Based Companion Strategies for the Vegetable Garden.

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

ARS Telescoping Long Reach Pruner

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

The Regenerative Landscaper: Design and Build Landscapes That Repair the Environment

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in