Healthy soil provides a building block for healthy plants, so wouldn’t it be great if plants could give something back? In some cases, they do. That’s the purpose of cover crops: plants grown specifically to benefit the soil and plants subsequently grown in that soil.

Cover crops improve soil on a number of levels. As their coarse and fine roots push through the soil, they shove some particles apart and release glues that bind other particles together, creating a network of pores that help air and water move into and through the soil.

Cover crops also protect soil by protecting the surface against wind erosion and softening the impact of raindrops. The deep roots of most cover crops can also latch onto nutrients leached down beyond the reach of other roots and bring them up to the surface for the next crop to benefit from. And the dense growth of a cover crop can keep weeds at bay by starving them for light.

What remains after a cover crop dies is as important as its living components. These remains contribute organic matter, which releases nutrients during decomposition, improves assimilation of nutrients already in the soil, and feeds microorganisms to create a healthy soil web.

Cover crops can do wonderful things for soil. Here are a few of the top cover-crop options, how to plant them, and how to get rid of them to make room for more plants.

Each cover crop has its own benefits

Grasses and legumes are the plants most commonly used as cover crops. Grasses—plants such as rye, wheat, and oats—are valued for their extensive root systems. Legumes—which include clover, beans, and peas—are most valued for their ability to grab and use nitrogen from the air (which is about 80 percent nitrogen) rather than taking it from the soil. Nitrogen incorporated into the living legume plant becomes available as these plants decompose to feed subsequent garden plants, replacing the need to apply nitrogen fertilizer.

Mustard and buckwheat, neither of which is a grass or a legume, are sometimes used as specialty cover crops. During decomposition, mustard releases chemicals into the soil that suppress certain weeds and soil-borne pests. Buckwheat’s strengths are making phosphorus more available to plants and smothering weeds.

Although cover crops require space to grow, there are plenty of growing options that will give you all the benefits without sacrificing too much garden real estate. One possibility is to mix in cover crops among other plants. This works for cover crops that aren’t overly competitive. Crimson clover, a legume bearing lollipop like red flower heads, is an excellent option because it’s attractive even as it improves the soil.

Another planting option is to squeeze in a cover crop either before or after a vegetable crop because many vegetables are not in the ground from the beginning to the end of the growing season. Even a chilly USDA Hardiness Zone 5 garden allows plenty of time for a cool-season cover crop, such as oats, to follow summer vegetables, such as cucumbers and squash. I’ll plant oats or barley up to the end of September. Rye grain, another option, grows well in fall, goes dormant in winter, then resumes growth in early spring. It’s a perfect cover crop to precede tomatoes, which can’t be planted in spring until after the last frost.

Removing a cover crop is as simple as you make it

Once a cover crop has done its job, you can replace it with other plants. The trouble is that cover crops don’t always die at the right time, and you’ll have to find some way of removing them.

Fact:In 1937, a soil scientist found that a single rye plant growing in a cubic foot of soil had grown 385 miles of roots and 6,600 miles of root hairs after only four months. |

Cover crops are most commonly either rototilled or hand-dug into the ground. Two potential problems exist with this method. First, you can’t dig or rototill until the soil is in good condition (not too wet or too dry). A cover crop, such as rye grain, is going like gangbusters by the time you’re ready to kill it in spring, making mixing it into the soil difficult. Second, digging negates many of the cover crop’s benefits, disrupting soil structure and soil organisms and charging the soil with so much air that organic matter is burned up.

To avoid disrupting the soil, you can kill cover crops by mowing. Mowing just as the cover crop is beginning to flower generally kills it, but if you miss this window, two or three mowings at other times will also work. Leave mowings on the ground, or if soil warming needs to be hastened, rake up the cuttings and use them for mulch.

I use the easiest technique to kill cover crops: I plant a cover crop that grows well in cold weather but doesn’t survive a snowy New York winter. Three such cover crops—oats, barley, and field peas—thrive in fall’s cool weather but are dead by February. Come spring, I can leave it where it is or use a rake to roll it up like a bedroll.

One of my favorite things about cover crops is the lush green carpet they form over the ground. It’s much prettier than bare soil, and it’s nice to know that all that green is working for a good cause.

There’re more than one cover crop

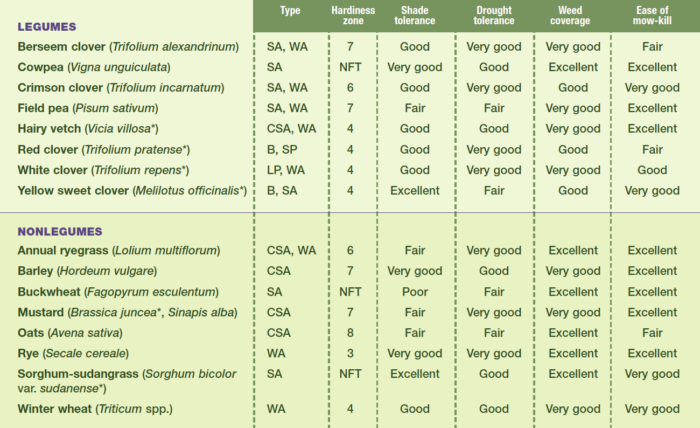

Don’t pick just any cover crop, pick one that works best for you. Need something for a shady corner? Want to squeeze out weeds? Use the chart below to help guide you toward your perfect match.

| Key

B = Biennial: A plant with a twoyear life cycle, flowering during its second year CSA = Cool-season annual: An annual that prefers cool growing conditions LP = Long-lived perennial: A perennial that typically lasts more than five years NFT = Not frost tolerant SA = Summer annual: An annual that prefers/ tolerates warm, dry growing conditions SP = Short-lived perennial: A perennial that typically lives for three to five years WA = Winter annual: A cold-tolerant annual that requires a cold period or freezing temperatures to set seed |

Lee Reich is a soil scientist in New Paltz, New York.

Photos, except where noted: Lee Reich

Sources:

- Johnny’s Selected Seeds, Winslow, Maine; 877-564-6697; johnnyseeds.com

- Peaceful Valley Farm Supply, Grass Valley, Calif.; 888-784-1722

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

The Regenerative Landscaper: Design and Build Landscapes That Repair the Environment

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

A.M. Leonard Deluxe Soil Knife & Leather Sheath Combo

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Ho-Mi Digger - Korean Triangle Blade

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in