Gooseberries have always seemed so British. Over there, no fruit lover would be without a gooseberry bush. Enthusiasts go one step further, joining gooseberry clubs and entering shows to see who can grow the largest berry. Contestants have been known to prepare by carefully thinning excess fruits from the bushes, and using such esoteric practices as “suckling” promising berries (perching a saucer of water beneath a berry just high enough to wet only its far end), and encouraging chickweed growth to increase humidity.

Here in America, however, gooseberries are not well known. But this has not always been the case. Early settlers brought European varieties to the New World, eventually hybridizing them with native American species.

The first hybrid, ‘Houghton’, debuted at the 1847 meeting of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society. Other varieties with American “blood” soon followed, and gooseberry growing and breeding in America was on the rise. The promising career of the gooseberry here was abruptly halted early in the 20th century when the plant was implicated in the spreading of a disease that also attacks white pines.

The popularity of this wonderful fruit is again on the upswing. This is thanks, in part, to the efforts of the International Ribes Association in spreading the word about gooseberries. Also, specialty nurseries have begun offering better-tasting varieties.

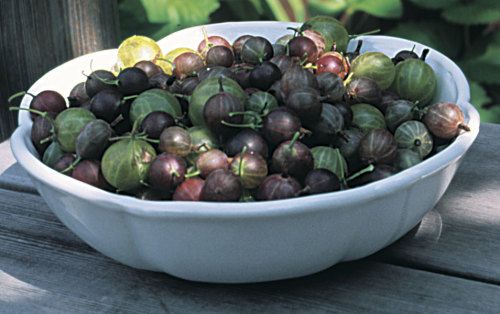

Gooseberries come in many flavors and colors

A fully ripened dessert variety of gooseberry is as luscious as the best apple, strawberry, or grape. In fact, the flavor of gooseberry was considered much like that of grapes in 17th century England, to the extent that gooseberries were raised commercially for fermenting into a delicate summer wine.

| Sources for gooseberries Raintree Nursery 391 Butts Rd. Morton, WA 98356 360/496-6400 www.raintreenursery.com Southmeadow Fruit Gardens |

|

Over the years, I have grown more than 40 varieties. Some, such as ‘Pixwell’ and ‘Mt. Ennis’, were tough and nothing more than sour. The ones I have kept are those whose tender skins envelope an aromatic, tasty pulp. These include ‘Hinnomaki Yellow’, which is fairly disease resistant, with berries that taste somewhat like apricot; ‘Achilles’, a large berry, mostly green with a blush of red and the taste of a well-ripened dessert grape, but with large thorns and high susceptibility to mildew disease; ‘Captivator’, a disease-resistant and almost thornless plant, with small to medium berries that have purplish-pink skin and good flavor; ‘Black Satin’, a disease-resistant, spreading bush, with small to medium fruit that is dark and has sweet, grapelike flavor; ‘Poorman’, a large upright bush that is disease resistant, with small to medium fruit that is pear shaped, reddish, and has good sweet-tart flavor; and ‘Red Jacket’, a large, upright, disease-resistant bush with medium-size, red fruit that has sweet-tart flavor.

The gooseberry bush itself has arching branches that give it a height and spread of 3 to 5 feet. The flowers are self-fertile and open early in the season, but are inconspicuous. Best production is on stems 1 to 4 years old. Gooseberries can be accommodated throughout much of the northern half of the United States if plants are mulched heavily to keep their roots cool, given some shade where summers are torrid, and irrigated where natural rainfall is deficient.

| Gooseberry recipes:

• Gooseberry and Sweet Cicely Cheescake |

|

Gooseberries are less finicky than most other small fruits about soil acidity and tolerate a wide range of soil types, except those that are waterlogged. Where summers are hot, bushes grow better and produce better fruit in heavier soils, which retain more moisture and stay cooler.

Plant gooseberry bushes 4 to 6 feet apart, the precise distance depending on the vigor of the variety and the richness of your soil. Since gooseberry plants are impatient to grow in spring, I set bare-root plants in the ground either in the fall, using plenty of mulch, or as early as possible in spring.

[[[PAGE]]]

Prune to keep 1-, 2-, and 3-year-old shoots

The usual way to grow gooseberries is as a “stool,” a huddle of stems that arise from the ground. New shoots come up annually, and the oldest ones are regularly cut to the ground. You’ll recognize them because the bark begins to peel on older stems, which also are thicker than younger ones. During the winter following the plant’s first season in the ground, begin training the plant by cutting away all but six of the previous season’s shoots. Do the same after the second winter, so that the bush has six 1-year-old and six 2-year-old shoots. Following the third winter’s pruning, the bush will have six each of 1-, 2-, and 3-year-old stems, the status you want to maintain.

|

|

| Gooseberry bushes can have a height and spread of 3 to 5 feet. When pruning, keep all 1-, 2-, and 3-year-old shoots and cut out anything older than 3 years. | |

In the fourth and subsequent winters, pruning consists of cutting down all 4-year-old shoots and all but six of the most vigorous, upright new shoots that grew from ground level the previous season. Also, shorten lanky shoots, if necessary.

Another way of growing a gooseberry plant is as a standard, or small tree. Standards look tidy, are decorative, and keep fruits off the ground. There is, however, the risk of losing a whole plant should its single trunk be damaged.

Train a standard by allowing only one stem to develop on a young plant, then staking this trunk-to-be upright. Nip out the tip of this stem when it reaches 2 to 3 feet in height, and side branches will form just below your cut. Prune the multibranched “head” of your mature standard as if it were a stool or let permanent side branches develop and periodically cut back stems arising from these, to maintain a constant supply of younger, fruitful wood.

White patches mean trouble

|

|

|

|

|

|

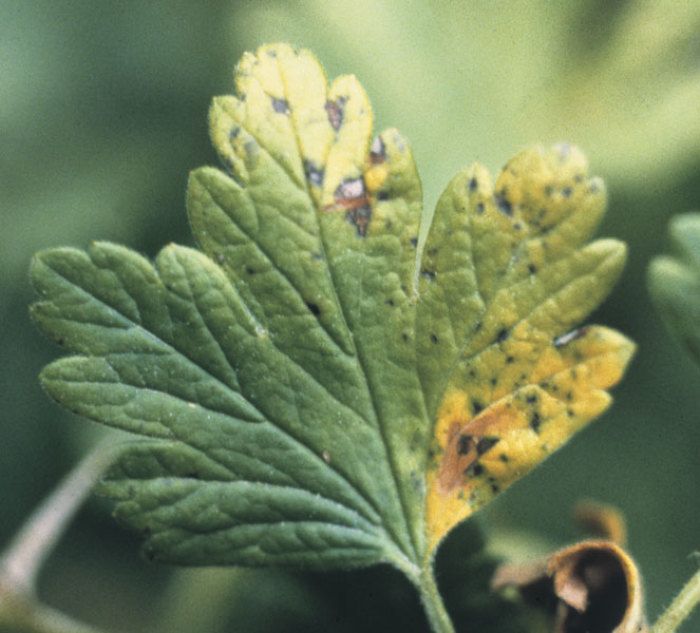

| Gooseberries are vulnarable to several diseases and pests, including powdery mildew (top), leaf spot (middle), and gooseberry fruitworm (above). Choosing disease-resistant varieties can heop minimize damage to a crop. | |

Powdery mildew is the most serious disease of gooseberries, ruining the fruit overnight on susceptible plants when days are clear, nights are cool, and spores are present. Powdery white patches, which eventually turn dark gray, develop on leaves and fruits. Much of the effort in gooseberry breeding in the 20th century has been directed, and successfully, toward developing mildew-resistant varieties.

I control disease on susceptible varieties in a few ways. Weekly sprayings of baking soda and summer oil—one tablespoon of each per quart of water—are supposed to be effective, though I haven’t found them to be dramatically so for me. I’ve had more success experimenting with a light mineral oil spray called Stylet-Oil, also applied weekly or biweekly.

I have also effectively eliminated mildew by cutting dormant plants to the ground, cleaning up all traces of leaves and stems, then moving the plants to a new site far from any infected gooseberries. (Rose and lilac powdery mildews are not threats because they are caused by different fungi.)

Leaf spot, which causes spotting, then loss of leaves, also can hit gooseberries. Fortunately, leaf loss usually occurs late enough in the season that I can ignore the disease, with no great harm done to my plants. Applications of Bordeaux mixture, beginning just after the leaves appear, are reputedly effective in controlling leaf spot, and lime-sulfur sprays are to a lesser degree. Varieties differ in their susceptibility to leaf spot diseases, and those previously mentioned as resistant to mildew are also resistant to leaf spot.

Two insect pests that require attention are the imported currantworm and the gooseberry fruitworm. I grew gooseberries for almost two decades without seeing either pest, or even mildew. But all three problems eventually found their way into my garden as I brought in new plants from around the country.

Currantworms begin their work just as leaves expand in spring, chewing at and quickly stripping the leaves. An organic insecticide, such as rotenone, applied as soon as damage is evident controls the currantworm, although subsequent sprays may be needed if the second or third generation becomes a problem.

Gooseberry fruitworm damages berries rather than leaves. Just before fruits ripen, these insects burrow into the berries, eat the pulp, then exit and spin a silken webbing joining fruits and sometimes leaves together. Damaged fruits color prematurely. A microbial insecticide containing Bacillus thuringiensis, such as Dipel or Thuricide, applied as soon as the webbing is evident, controls the fruitworm.

Two ways to propagate gooseberries

The ease with which gooseberries propagate from cuttings depends on the variety. Generally, American varieties are easier to propagate than European ones. Take hardwood cuttings in early fall, even before all the leaves have fallen from the plants. The presence of a few leaves actually enhances rooting. Make cuttings about a foot long, but do not include tip growth, and bury them so that only the top bud is exposed. Mulch after the ground freezes, then remove the mulch in early spring.

For easier propagation of just a few plants, try tip layering. Bend a stem tip to the ground in spring, cover it with a little soil, and anchor it with a rock. Roots will form where the stem touches soil, and a small plant will be ready for transplanting either by that first fall or, with difficult-to-root varieties, the following fall.

Watch out for the thorns

|

|

| To harvest gooseberries, hold a branch back with one hand, and carefully pick with the other to avoid the numerous and vicious thorns. | |

In my garden in New Paltz, New York, I begin harvesting around the first week of July. I find it easiest to pick gooseberries in quantity by holding up a branch with one leather-gloved hand while I strip fruit with my other, ungloved, hand. Gooseberries are one of the few fruits usually picked underripe and then cooked.

But don’t let this overshadow the pleasure of eating the fully ripened fruit right from the plant. Once you gain appreciation for the fresh, ripe fruit, the goal becomes to seek perfection in flavor. Though opinions differ on whether ripe gooseberries taste best early in the morning, still cool from the night air, or at noon after being warmed by the sun, the fresh fruit is at its best plucked straight from the bush and tossed into your mouth. As Edward Bunyard said in The Anatomy of Dessert in 1934, “the Gooseberry is of course the fruit par excellence for ambulant consumption.”

October 2000

from Kitchen Gardener, issue #29

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

Corona High Performance Orchard Loppers

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

A.M. Leonard Deluxe Soil Knife & Leather Sheath Combo

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Berry & Bird Rabbiting Spade, Trenching Shovel

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in