Gertrude Jekyll, the doyenne of early-20th-century British gardening and mother of the modern mixed border, was ever the optimist. On at least one occasion in her later years, however, she admitted that building a garden takes up about a third of one’s time on earth—in learning and putting that knowledge into practice.

After a third of a century of creating, tweaking, and fine tuning, my garden of mixed borders is no exception. It continues to evolve and change. One of the biggest changes occurred after a trip to England to visit Great Dixter, the world-class garden and manor house of Christopher Lloyd, built in 1460. After our trip overseas, I announced to my wife, Peggy, that I wanted to tear up our (then) 18-year-old garden and reinvent it to mimic the idyllic English garden feel of Great Dixter.

My own “Tennessee Dixter,” a modest emulation of Great Dixter, is still a work in progress. This long border (actually a series of borders) is not only an oasis but also an ever-changing project, which shows that a garden doesn’t have to continue to follow one style started years ago. It can—and should—grow and evolve with you. I use three points to build and maintain continuity and beauty in my ever-changing long border: distinct areas within each border, repetition of key elements, and gradual transitions between borders.

Create diversity without distraction

Whether you’re planning a small bed or one big border, start with a strategy. Otherwise, you may end up with a disjointed, visually unappealing series of plants. Incorporate these elements to create unity within an existing border and to maintain cohesiveness through any future additions.

1. Distinct areas within the border

A formal evergreen container, surrounded by a large grouping of pink phlox constitutes a distinct area within this lengthy stretch of border.

2. Repetition of key elements

The pink of the phlox appears throughout the border in the same or similar plants, leading the eye effortlessly along.

3. Gradual transitions

This arbor, in combination with the climbing vines, provides a smooth segue from one garden area to another.

Defy monotony by maintaining distinct areas within the border

When designing a border garden—whether you complete it in one fell swoop or, like I have, take years to add and re-create sections of border—it is important to establish distinct areas within each section to give it life. Diversity, of course, can easily lead to distraction when there is too much of it. The plant collector’s mania always fights with the designer’s restraint, with the plant collector often winning. It’s all about establishing balance.

Many of the British and other European gardens that I admire are planted exuberantly with masses of informal flowers within formal frameworks, but because the beginnings of my garden were started with informality, I reversed this theme to incorporate distinct formal areas within an informal layout. I establish these formal areas by mixing in yews, box hedges, and stone walls. Pruned into balls, cones, or clouds, boxwoods prove to be valuable in winter when most perennials dissipate. After leaf fall, the boxwoods seem to jump out of their surroundings. Distinct formal areas are also established by the inclusion of urns, large pots, and topiaries. On the face of it, this reversal to formal within informal, rather than vice versa, would seem incoherent. Surprisingly, however, it works.

Large groupings of the same or similar plants also create distinct areas that defy monotony. I depend on summer phloxes, for instance, to pull this off during their season. Big groups of phloxes of the same color dominate in July and August, but they do not overwhelm because, nearby, there is such a plethora of foliage and other colors.

The parts of the border, however, should always be in direct relation to the whole. One way I attempt to avoid the perception of “too much” is to leave a couple of areas in the front of borders for annuals. These are always in one color per location, and the color is one that will blend with perennials of the season. I follow cool-season annuals (violas, pansies, and dianthus) with summer annuals (impatiens, vinca, and wax begonias). These annual plantings produce an effect almost year-round.

Create unity with repetition

Repetition within a border establishes continuity, which is an essential part of every garden. It leads the eye, drawing you seamlessly from one section of border to the next. When done well, you barely notice that it’s happening.

An easy way to establish repetition is through plant selection. I am enamored with large, bold plants in my borders, and use numerous cannas (Canna spp. and cvs., USDA Hardiness Zones 8–11), large coleus (Solenostemon scutellarioides cvs., Zone 11), hostas (Hosta spp. and cvs., Zones 3–9), and hardy begonias (Begonia grandis subsp. evansiana, Zones 6–9).

The key to successful repetition with plants is to remember that repeating something doesn’t mean that each feature is identical. I use cannas, for instance, in my borders to provide a contrast to fine-foliage plants. But the cannas are different varieties, heights, and leaf shapes. They constitute repetition but not to the point of boredom.

And, no, the repetition does not have to be of bold plants, either; simple plants can be just as effective. I use liriope (Liriope spp. and cvs., Zones 6–10) in my rock-wall border but in a variety of group sizes and mixed colors.

Color is a great means of repetition, and my borders are all color coded to a certain extent. Most of them are pastel, possibly due to reading too much British-gardening literature. Pastels in the southern United States do have a tendency to wash out, though, which explains why I started a red border in the 1990s. I pull off this bold move from pastels to bright reds using transitional elements.

Fuse borders using gradual transitions

Once repetition is established, it’s important in borders like mine—where the long border is actually numerous small gardens joined together—to create a gradual transition from one section of border to another. For gradual transitions, I have found that one of the best ways to blend one group of more prominent perennials with another is with the use of climbers or other plants that weave among their neighbors.

I especially like using perennial geraniums, my favorite among them being hardy geranium (Geranium sanguineum var. striatum, Zones 3–8). These geraniums, standing alone, will top out at 8 inches but easily climb to 18 inches when combined with and allowed to grow into neighboring perennials or shrubs.

My borders also have distinct dividing points that help provide a transition from one section of border to the next, though these are minimal. One border is broken from another, for instance, by a cross path and an arbor with climbing vines. Another arbor joins two other sections of border. Similar colors at adjoining ends of borders soften any change and keep the transition from being too abrupt.

There is one exception to these examples: A 12-foot-wide swath of lawn separates a shaded section of pastels (mostly self-seeded impatiens in summer and fall) and the red border in full sun. In this case, the transition is more dramatic, and I will say, in all modesty, that some visitors have audibly gasped when turning suddenly from the soft shade colors to the brilliant reds and oranges in full sun. Even here, however, continuity is achieved by using stone mowing strips, pillars, and matching containers to provide a transition from the final pastel border to this hot-colored section of border.

In the grand scheme of things, a third of a century isn’t a long time to create and work with a garden you love. With a little know-how, you can easily continue to change and expand your garden year after year. Don’t be daunted by the fact that it might take years to build. Start planting. After all, once you start, at least there will be something there the next day.

Lengthen your garden’s performance

I am disappointed if I do not get at least 10 months of attractiveness from most of my mixed borders. I usually pull this off by following a few simple steps.

Don’t skimp on bulbs and blooms

If you do some research and planning to get the timing right, you can have blooms from late winter right into summer. Most years, I have hundreds of crocuses, early daffodils, and snowdrops on the move by the end of January.

Use evergreens to extend the season

Spring and summer are a garden’s prime time, but shrubs and small trees keep the border going late into the gardening season. Many ornamental grasses also last well into winter, carrying on until after Christmas in our climate.

Put in some hours

Regular deadheading and trimming are a prerequisite to season-long appearance—this garden is no low-maintenance wonder. I will even pull some midsummer derelict that has decided to decline and plop in a stop-gap annual or shrub.

Jimmy Williams, garden columnist for The Paris Post-Intelligencer, gardens at his home in Paris, Tennessee.

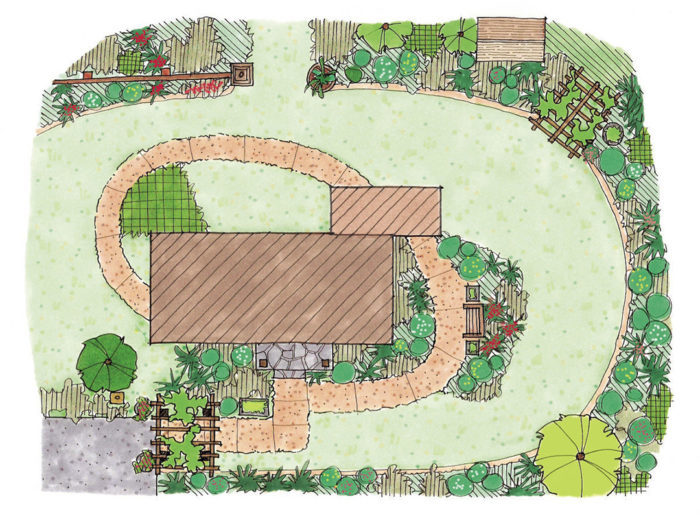

Photos, except where noted: Steve Aitken. Site plan: Martha Garstang Hill.

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

Buffalo-Style Gardens: Create a Quirky, One-of-a-Kind Private Garden with Eye-Catching Designs

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

A.M. Leonard Deluxe Soil Knife & Leather Sheath Combo

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

The Crevice Garden: How to make the perfect home for plants from rocky places

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

These are all such lovely ideas and I'd love to incorporate them into my rather pizazz-less border, but there's one obstacle. Money. The conifers I can afford will not contribute much in the near future. A stone wall would be lovely, and I'm digging them up as fast as I can, but I'm not sure the one I build will be so nice. I do repeat elements, all of them, because my primary means of obtaining new plants is dividing the old ones.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in