For many years, persicarias—also known as knotweeds—inhabited the periphery for me. I saw them but mostly looked past them, thinking of them as filler more than thriller. My first genuine appreciation came nearly 20 years ago after spotting a commanding swath of crimson-spired ‘Firetail’ nestled in a sea of palm sedge (Carex muskingumensis, Zones 4–9) in a new display garden at the Chicago Botanic Garden. Stylized meadows of this sort, championed by the landscape architects at Oehme van Sweden, are the perfect showcase for bold yet uncomplicated perennials like persicaria. With my interest piqued and eyes now wide open, my persicaria sightings became more frequent and satisfying. A trial to get to know them better was on my mind for years, but it took one notorious persicaria to finally make it happen.

Persicarias At a Glance:Persicaria spp. and cvs. Zones: 4–9 |

Reasonable concern over the potential rambunctious nature of persicarias is justifiable, but a movement to banish all persicarias from our gardens was worrisome. Yes, the garden value of persicarias stacked against their potential invasiveness is a “knotty” subject. A closer look, though, shows that they’re not all thuggish; in fact, there are many garden-worthy persicarias.

Top performers worth planting

‘Firetail’ mountain persicaria

‘Firetail’ mountain persicaria (P. amplexicaulis ‘Firetail’) is pretty easy to like: a seemingly endless bloom of vivid crimson spikes sit atop bushy plants from late spring to early fall. The flower color is particularly vibrant on crisp autumn days. A dash of red accents appears in midsummer, and the medium green, arrowlike leaves lighten a bit as summer wanes. ‘Firetail’ proved similar to ‘Atrosanguineum’ in its bushy habit and size, but I liked the richer flower color of ‘Firetail’ more. All things being equal, ‘Firetail’ would have been top rated, but a bit of crown injury in multiple winters cost it a star.

‘Rosea’ mountain persicaria

The pale pink flowers of long-blooming ‘Rosea’ mountain persicaria (P. amplexicaulis ‘Rosea’) rise generously above dark green leaves from midsummer to late midfall. While ‘Rosea’ presents quite a good flower show, I never found the soft pink as satisfying as the vivid reds of ‘Firetail’ or ‘Summer Dance’. The tiny flowers opened randomly along tapered spikes up to 7 inches long and were busy with bees for weeks on end. Stout ‘Rosea’ formed big bushy mounds reaching nearly 5 feet tall and wide by the end of summer. Unlike a few similar persicaria, ‘Rosea’ was fully winter hardy but was not aggressive or weedy.

‘Summer Dance’ mountain persicaria

Mountain persicaria tends to be a rounded clumping plant with large pointed leaves and slender floral spires in shades of red, pink, purple, or white. ‘Summer Dance’ mountain persicaria (P. amplexicaulis ‘Summer Dance’) embodied all the best attributes of this species and was the standard whereby others were judged. You can expect a beautiful profusion of uniquely bright coral-red flowers that dance above lime-green leaves for three full months. At 5 feet tall and wide, ‘Summer Dance’ has bragging rights for being the largest and most vigorous of the mountain persicarias in the trial. If you’ve got the room, give ‘Summer Dance’ a whirl.

‘Golden Arrow’ mountain persicaria

Golden-yellow leaves can be a tough sell—some gardeners have probably already tuned out—but ‘Golden Arrow’ mountain persicaria (P. amplexicaulis ‘Golden Arrow’) is worth a closer look. Radiant gold in spring, the leaves cool to soft yellow-green for the summer, although they are still vibrant enough to glow under the rosy pink flowers. This dramatic color combination is so stunning that you might not notice that the flower spikes are only 3 inches long. ‘Golden Arrow’ is diminutive compared to other cultivars, featuring smaller, fine-textured arrow-shaped leaves and a low, mounded habit just 26 inches tall. Too much sunlight bleaches the leaves white, so ‘Golden Arrow’ is best grown in partial shade.

‘Border Jewel’

There is no mistaking the kinship of ‘Border Jewel’ (P. affinis ‘Border Jewel’) to other persicarias, but rather than being mounded and bushy, it is a ground-hugging spreader. Tiny pink blossoms burst from vibrant pink buds, then age to pinky orange before finally turning burnt orange to russet. Due to the long bloom period, all flower stages and colors are present at the same time. Green leaves accented with red and orange add to the kaleidoscopic effect throughout the season; leaves hold russet for the winter, so fussy gardeners may want to do some spring cleanup. ‘Border Jewel’ can spread widely but was not aggressive—it moved into ‘Dimity’ but didn’t seem willing or able to compete with larger neighbors.

Giant fleeceflower

Giant fleeceflower (P. polymorpha) is a gentle giant—bold enough to knock your socks off in bloom but mild-mannered enough to shake the stigma of being thuggish. Even before the flowers appeared, I loved the uniformity and uprightness of its clumping habit: it formed right out of the ground in spring as perfect balls. Its hulking shrublike habit may give pause, but its size is only a problem in small gardens. You don’t have to wait long for the big show, because the teeny white blossoms gathered in large frothy plumes open in late spring and go on for weeks. My evaluators differed greatly in describing the fragrance: from a light, pleasant scent to a disagreeable odor. I’ll let you break the tie. Shear it when the first blooms pass for a second flower display.

Uncommon gems to search out

‘Fat Domino’ mountain persicaria

A number of wonderful persicarias have come from Belgian plantsperson Chris Ghyselen, and while not exactly new, they aren’t as well known. Among them is ‘Fat Domino’ mountain persicaria (P. amplexicaulis ‘Fat Domino’), which was outstanding in its first year. Describing the intensity of the flower color is tricky—it’s dark orange-purple up close but sultry red-purple a short distance away. ‘Fat Domino’ was not shy to flower, pushing up chubby spikes one after another well into late fall. This plant’s striking color delighted me, as did its vigor. From tiny plants in late spring, ‘Fat Domino’ flourished, reaching 30 inches tall and wide by early fall, and 20 inches to the top of the green leaves. It looks like it will be brawny, more akin to ‘Firetail’. The fact that it thrived despite repeated deer browsing all summer is a testament to an indomitable spirit.

‘Orangefield’ mountain persicaria

‘Orangefield’ mountain persicaria (P. amplexicaulis ‘Orangefield’) has a unique chameleonlike flower color—paradoxically, the two-toned reddish and very pale pink (almost white) flowers look pink in shady light but decidedly orange in full sun. Its green leaves are narrower than those of other cultivars, giving it a more refined look, and are ringed in dark burgundy in fall. ‘Orangefield’ reached half its ultimate size of 3 feet tall and wide the first year in the trial, which reflects its vigor.

‘Blackfield’ mountain persicaria

‘Blackfield’ mountain persicaria (P. amplexicaulis ‘Blackfield’) is a dusky beauty, with dark purple-red flowers that caught and held my attention at first glance. The nearly black buds and deeply hued flowers were the darkest in the trial, although there is one out there called ‘Black Adder’ that allegedly is even darker. The fine-textured, lance-shaped leaves were significantly smaller in scale than those of other persicarias, but perhaps this was just a first-year thing. ‘Blackfield’ was 18 inches tall and 20 inches wide last summer, and like ‘Orangefield’, it feels petite compared to other cultivars, although it too is expected to be 3 feet square. Truth be told, I grew ‘Blackfield’ several years ago, but it didn’t make it through a winter. I definitely waited too long to try it again.

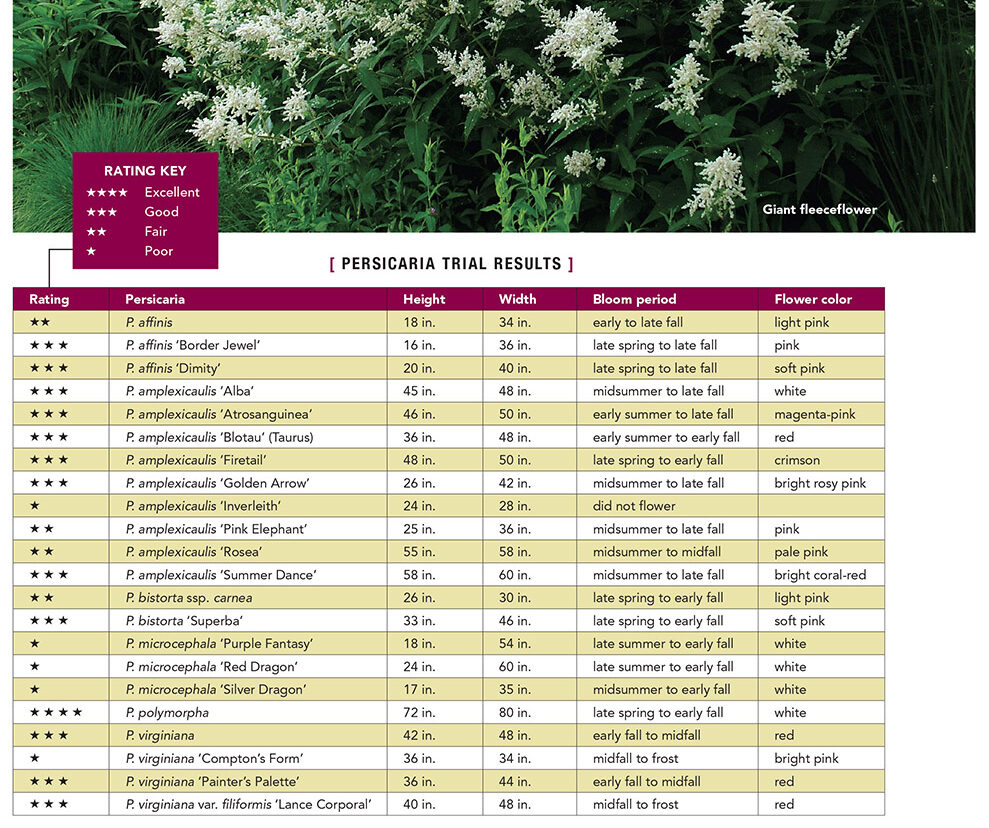

Trial parametersThe Chicago Botanic Garden is evaluating 30 different persicarias in ongoing comparative trials. In 2011, a previous trial ran afoul of an errant bulldozer during garden renovations, so we started over again in 2012. Participants mainly included selections of Persicaria spp. and Fallopia japonica; numerous nomenclatural changes over the years have complicated the classification of these two groups. Duration: 7 years Zone: 5b Conditions: Full sun; well-drained, alkaline, clay-loam soil Care: We provided minimal care, allowing the plants to thrive or fail under natural conditions. Besides observing their ornamental traits, we monitored the plants to see how well they grew and adapted to environmental and soil conditions while keeping a close eye on any disease or pest problems and assessing plant injury or losses over winter. |

Persicaria: Friend or foe?

You might be asking yourself at this point, “Isn’t the horribly invasive Japanese knotweed a persicaria?” The answer is yes—and no. Although formerly designated to the genus Persicaria, Japanese knotweed is now Fallopia japonica. Japanese knotweed is perhaps the archetype of an invasive plant, and its status as a noxious weed is universally recognized: it’s on the list of the world’s worst 100 invasive species. Despite all this, a few “ornamental” varieties of Japanese knotweed are readily sold to the gardening public. Knowing this, we decided to do a trial of Japanese knotweeds at the same time as our persicaria trial.

Note: The straight species is not a desired plant, so it wasn’t obtained for the study.

Characteristics

Japanese knotweed is an upright shrubby perennial with stout bamboolike stems reaching to 15 feet tall. The large green leaves—to 6 inches long—are broadly egg-shaped with pointed tips. Sprays of white flowers crown the plants in late summer. Variegated and shorter variations also exist.

How they spread

As startling as knotweeds are above ground, it’s what’s going on underground that is more troublesome. A vast network of thick rhizomes can travel up to 60 feet from the plant’s nexus. Japanese knotweed spreads rapidly, forming dense thickets that shade and crowd out native plants, thus threatening natural ecosystems, species diversity, and wildlife habitat. Once established, it is extremely persistent and difficult to eradicate. Shoots can sprout from small rhizome fragments buried up to several feet deep and can punch through asphalt.

Reports from other sources note that seeds are produced but are rarely viable, yet seed dispersed by wind, water, animals, humans, or in soil is cited as a primary mode of spreading.

Trial participants

- F. japonica var. compacta

- F. japonica var. compacta ‘Variegata’

- F. japonica ‘Crimson Beauty’

- F. japonica ‘Devon Cream’

Length of trial: 6 years

Hardiness

While listed as cold hardy to USDA Zone 5, the fact that it has naturalized in northern states, Alaska, and most of Canada implies its adaptability to extreme climates. In other words, no place is safe.

Names

Japanese knotweed may be labeled as Polygonum cuspidatum or Reynoutria japonica. In fact, the many names and synonyms of knotweeds—Polygonum, Reynoutria, Tovara, Fallopia, and Persicaria—muddy the water and may call into question what plant you’re actually getting.

Trial findings

Potential invasiveness was measured by the vigorous rhizomatous habit rather than seedlings, which were never discovered. The vigor of these selections was obvious from the start, and none contained themselves to their given space after several years. ‘Devon Cream’ was by far the scariest of the Japanese knotweeds, spreading over 20 feet in all directions and into the turf by the fourth year. And its vigor and flower production only increased when the taupe-speckled variegation began to be overrun by reverted green-leaved stems.

Mitigation

With the trial now over, I fear the titan we’ve unleashed. The question remains how long it will take to remove these plants from our garden. We’ve begun by manually digging out rhizomes, but we will likely have to pair this practice with some chemical treatments. Japanese knotweed and all its selections have been firmly placed on our “Do not plant” list.

Richard Hawke is plant evaluation manager for the Chicago Botanic Garden in Glencoe, Illinois.

Sources:

- Digging Dog Nursery, Albion, CA, 707-937-1130, diggingdog.com

- Far Reaches Farm, Port Townsend, WA, 360-385-5114, farreachesfarm.com

- Plant Delights Nursery, Raleigh, NC, 919-772-4794, plantdelights.com

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

A.M. Leonard Deluxe Soil Knife & Leather Sheath Combo

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Gardener's Log Book from NYBG

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Buffalo-Style Gardens: Create a Quirky, One-of-a-Kind Private Garden with Eye-Catching Designs

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in