In 2005 I killed my front lawn. It wasn’t negligence or ignorance. It was premeditated, cold-spirited, calculated murder. It’s not that I don’t appreciate turf grass. It most certainly has its benefits, both visually and functionally. But there were too many downsides for me. It required considerable water during the heat of summer, which was both impractical and expensive here in Fort Collins, Colorado, where annual rainfall averages a meager 15 inches. My front lawn was also susceptible to fungal diseases, fairy ring in particular. It collected dead spots where passing dogs had mistakenly marked it as their territory. And it required loud and obnoxious weekly mowing, which upset the serenity of a neighborhood tucked peacefully against the Rocky Mountain foothills.

What I really wanted was to create a unique community focal point juxtaposed against the bland sea of the neighborhood’s ubiquitous Kentucky bluegrass. I wanted something that would provide wildlife habitat; minimize water, fossil fuel, fertilizer, and pesticide use; and eliminate air and noise pollution. However, the cliché xeriscape—a front yard filled with an array of cacti and ornamental grasses placed on a garish blanket of lava rock—would not be in keeping with neighborhood aesthetics or expectations. What I needed was a very lush look, but one that didn’t use 100,000 gallons of water every time the earth took a lap around the sun.

Kill the turf and rethink the water

Getting rid of my lawn took some doing. I found that the best time to tackle such a task is during the hot days of summer. First, turn off the water (no irrigation, sprinklers, or hand watering—at all) for a month. From there, focus on killing the roots below the surface. Methods to accomplish this include spraying with glyphosate, smothering with newspaper/cardboard, solarizing with plastic, or removing either by hand with a spade or mechanically with a sod cutter. Whatever method is used, it’s best to disturb the soil as little as possible to avoid activating weeds. I decided to leave the dead turf in place. It’s the easiest thing to do, and dead turf is an excellent weed barrier, helps retain soil moisture, and provides much needed organic matter as it slowly decomposes over five to six years. You may still need to do a bit of hand weeding for the remainder of the growing season when the occasional patch of stubborn grass decides to come back from the dead, but that should be it for the removal step. I killed the turf and let it sit all summer and winter. I didn’t plant or do anything else until the following spring, which is when I dug into the dead turf and installed an array of drought-tolerant plants.

The idea that a water-wise garden needs no water is false. It needs responsible amounts of water to establish the plants at first, and then periodic water later during periods of drought. So my next step was to retrofit my watering system. If your lawn has an existing underground irrigation system, you can easily convert it to a drip system using the existing spray valves and zones. The first step is to locate and change the spray valves in each zone to drip valves, which operate at a substantially lower water pressure. Next, starting at each valve, snake a drip line throughout the spray zone area. The drip lines can be installed directly on top of the dead turf. Punch emitters directly into the drip line, and run feeder tubes to the planting areas. Selecting the correct gallon-per-hour emitters will minimize water use (1 gallon-per-hour for perennials).

What’s going on below the surface

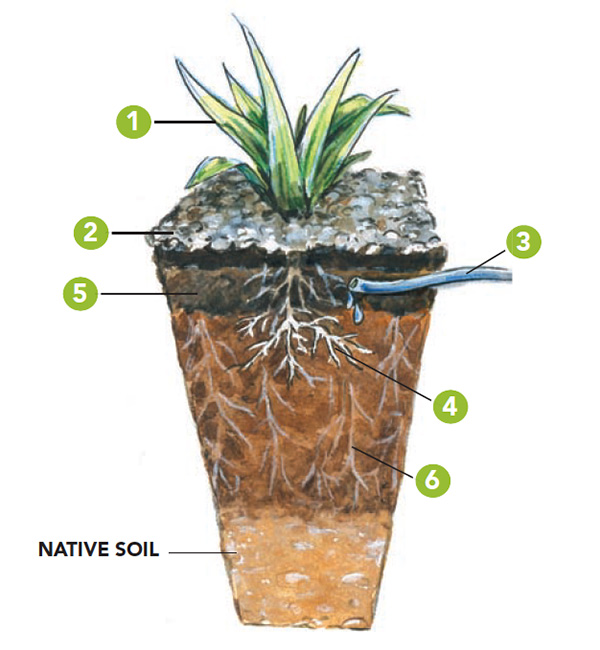

Here is how the dead lawn, gravel mulch, drip lines, and plants all form a symbiotic relationship.

1. New plant: Placed in dead turf

2. Gravel mulch: Helps retain moisture and deter weeds

3. Drip tubes: Useful for initially establishing plants

4. New plant roots: Reach through dead turf into soil

5. Dead turf: Provides organic matter as it slowly decomposes

6. Dead turf roots: Slowly decompose into existing soil

In addition to saving water, drip tubes minimize weed growth versus overhead watering. Drip irrigation is useful for both establishing plants during the first few growing seasons and supplying additional water on an as-needed basis during particularly hot, dry, and windy weather. If you don’t already have an irrigation system, you can purchase a relatively inexpensive one at local home stores. They’re easy to install and provide the same low-usage, high-efficiency watering. Soaker hoses are also a cheap and easy way to go.

Add a layer of untraditional mulch

If my neighbors thought I was crazy when I killed my entire front lawn, they surely would have thought I had lost it if I had just left the dead turf as it was. It’s important to mulch the dead turf, plants, and drip lines with pea gravel to a depth of 3 inches, which is not difficult to walk on; in fact, it provides a stable cushion underfoot. Do not use a fabric weed barrier, as it will interfere with plants spreading and reseeding. The pea gravel will help retain ground moisture and permit extensive reseeding of desirable plants as it collects solar heat during the day and subsequently releases it in the evening. Weeds may seed in, too, but they can be detected easily and extracted from the gravel with an asparagus knife.

Over time, as plants fill in and self-sow, the pea gravel becomes less and less noticeable. The gravel produces a hard, moonscape look initially, but then it gradually fades into a neutral background as time and natural elements weather it. You might wonder why I didn’t just mulch with shredded bark. After all, it is a less backbreaking material to work with. Initially, I did use bark mulch, but I found that it compacted over time and did not allow enough air and moisture to permeate the soil for the plantings to thrive. It also prevented nearly all self-sowing.

Plant choice is based on year-round texture and color

The thing that most folks like about lawns is that they are ever present. Sure, they may die in winter, but they still have a familiar texture that lets us know, “There’s a lawn here!” When you ditch the lawn for a garden, you need to be especially selective with your plant palette. I find that the most challenging seasons to sustain visual interest are late summer and winter. For winter, I made sure to pick ornamental grasses, dwarf conifers, and shrubs with interesting bark, such as redtwig dogwood (Cornus sericea, Zones 3–8). With few exceptions, I stuck to plants that stayed under 3 feet tall so they wouldn’t block the view to or from the house. Mossy rock boulders and weathered wood stumps and limbs also add visual interest. The grasses may get pushed down and broken by snow at some point, but they can be quite resilient. My favorite plant for winter that does well in xeriscape conditions is heath (Erica carnea and E. × darleyensis, Zones 4–7), an evergreen with needlelike leaves and small flowers.

Simple ideas for late summer include coneflowers (Echinacea spp. and cvs., Zones 5–9), ‘Blue Mist’ bluebeard (Caryopteris × clandonensis ‘Blue Mist’, Zones 6–9), and Russian sage (Perovskia atriplicifolia and cvs., Zones 4–9). My initial decisions of what to plant next to each other were made with the help of garden designer Lauren Springer. She taught me how to base pairings on contrasting textures, colors, and forms. As plants spread and self-sowed, I allowed my aesthetic intuition to guide decisions around what to keep in place and what to remove. I’ve always encouraged self-sowing and naturalizing through plant and bulb selection, which helps fill any potential gaps in the garden. I do come through and edit occasionally when things get unwieldy. When plants die and something new needs to be added, I try to pick something that goes well from a color, texture, and form standpoint but that also attracts wildlife and pollinators. One of my initial goals in getting rid of my lawn was to provide something more beneficial to the surrounding ecosystem.

I have found this garden to require less effort and expense, and to be more enjoyable and rewarding, than maintaining turf grass. But most importantly, I have found that countless passersby have been deeply touched by it and often take a moment to stop and express appreciation for my no-lawn front yard.

Hard lessons learned

When I first started this project, I figured I’d simply kill the lawn and plant some drought-tolerant varieties. Over the years, I have learned several things I wish I had known before I started.

Tree selection matters most

Finding the right trees for a front landscape is critical. Consider site characteristics and what plants will be able to coexist with the trees as they grow to maturity. When an existing tree died in the front yard, I replaced it with an Austrian pine (Pinus nigra, Zones 4–9). Even though this choice was drought tolerant and blended in well with the adjacent foothills, it is now too large for the site (photo above). It creates too much shade, severely limits the amount of water received by the surrounding plants, and drops an enormous volume of pine needles that need to be gathered up.

Pay extra attention to winter

This is the time of year that exposes the garden’s under lying structure. As the saying goes, “Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.” The first winter, when all the perennials died back to the ground, there wasn’t much left to look at except for some boulders and junipers. Weaving dwarf conifers throughout the landscape provided an interesting solution to this problem and now offers a year-round structure to reference and build from.

Don’t underestimate the visual impact of accent plants

Accent plants have unusual and remarkably striking foliage textures or colors that immediately draw the eye. These types of plants are best used sparingly and in the same manner you’d add a spicy-hot sauce to an exotic culinary dish. They create a vibrancy, sparkle, and delight that will be noticed immediately. I didn’t have any accent plants the first five years—just some tried-and-true perennials and a mix of drought-tolerant shrubs. Immediately after I introduced accent plants into the garden, passersby started to stop, stare, and take pictures.

Great accent plants

Patrick Quadrel maintains his water-wise garden, and a dozen rambunctious hops plants, in Fort Collins, Colorado.

Photos, except where noted: Danielle Sherry

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

Razor-Back Potato/Refuse Hook

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Morvat Heavy Duty Brass Y-Valve

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

- Fitted with US Standard NH 3/4" threads for use with most water source fittings

- Screw the 2 way splitter adapter by hand or wrench with the updated hexagonal top connection. The 360° rotatable swivel connection attaches to any water source.

Planting in a Post-Wild World: Designing Plant Communities for Resilient Landscapes

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Ditching the lawn was a great idea. Your yard is beautiful. If I was retired and had help, I would join you. :-) Thanks for sharing. Keep up the great work.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in