Haters have been around for a long, long time. They existed well before the late great legend of hip-hop the Notorious B.I.G. helped popularize the term to the mainstream in the 1990s. One might even argue that the first hater was a farmer named Cain who killed his brother Abel. In the case of Charles Edgar Dickinson, Jr., the first Black person admitted into the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA), haters were there at the start of his career, but his legacy has eclipsed them all.

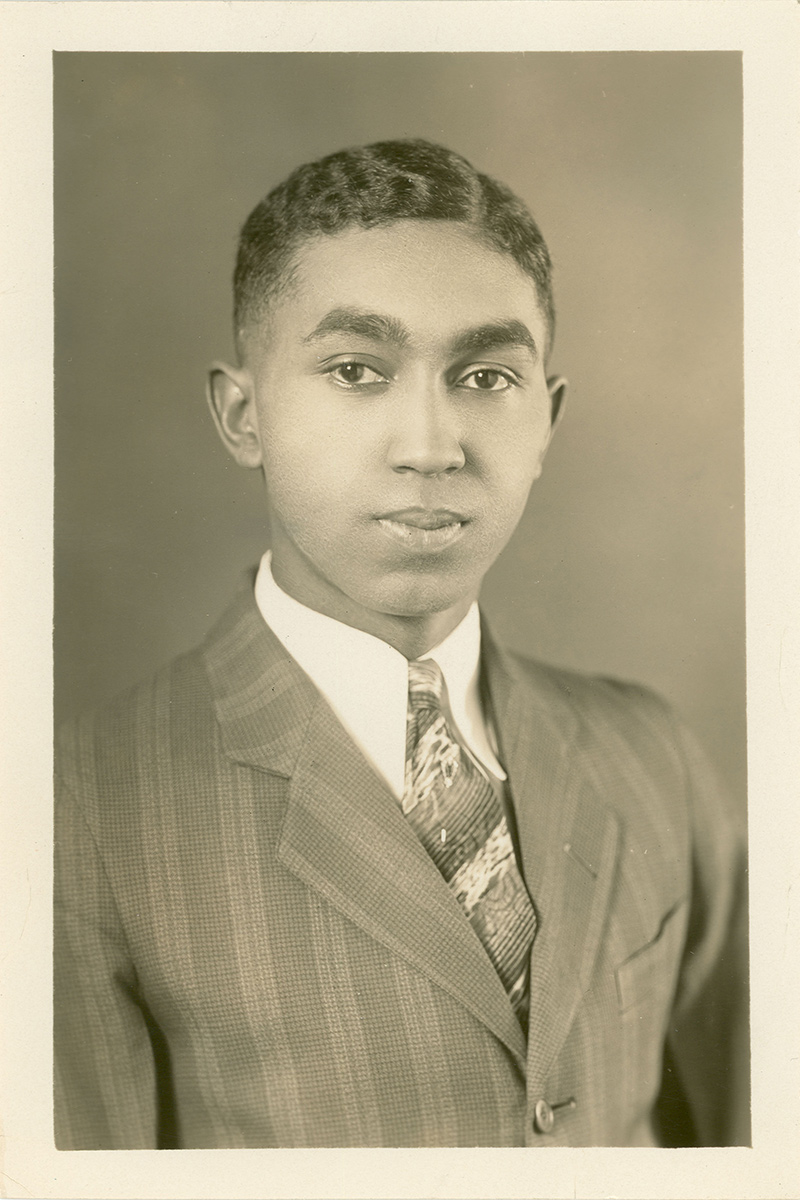

Dickinson was the youngest member of his class at The Ohio State University, and his friends and professors discouraged him from pursuing landscape architecture as a profession. They could not see a path to success for the aspiring designer. Yet by the time he graduated in 1930, Dickinson had proved to the haters what he himself knew to be true: Success was his destiny. While none of his classmates received employment offers upon graduation, Dickinson received multiple.

Horticulture and natural design were part of his pedigree

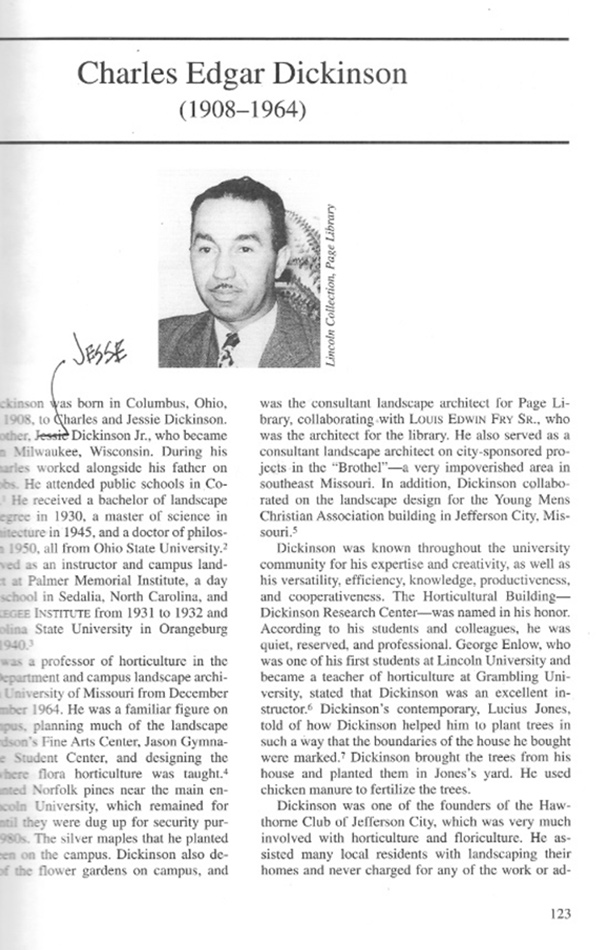

Dickinson was born into the nature lifestyle and into a prominent family, and there was little reason to ever doubt he would excel. His father, a professional gardener, owned and operated a landscape company in Dickinson’s hometown of Columbus, Ohio. Dickinson accompanied him on landscape jobs, and it was through this upbringing that the son learned “a wealth of practical experience.”

But he didn’t just learn the beauty of nature from his father. Dickinson’s mother was known for her exceptional entertaining skills—which included decorating the inside of their home with elements from nature. The interior of their residence often was draped with pink, red, and yellow gladioli, palms, ferns, snapdragons, and roses.

Embracing plants as a profession and a hobby

After graduating from college, Dickinson accepted an appointment at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, where he was tasked with landscaping the campus and teaching botany. He also worked as an assistant to the greatest “plant doctor” in the world—George Washington Carver.

After leaving Tuskegee, Dickinson moved on to teach at other schools, including two historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). The first was South Carolina State University, where he was a professor of horticulture and landscape architecture. Then in 1940 he joined Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri, a school founded for free and formerly enslaved people by Black soldiers who fought in the Civil War. Dickinson spent 24 years as a prominent member of the Lincoln faculty and left a lasting impact on the community.

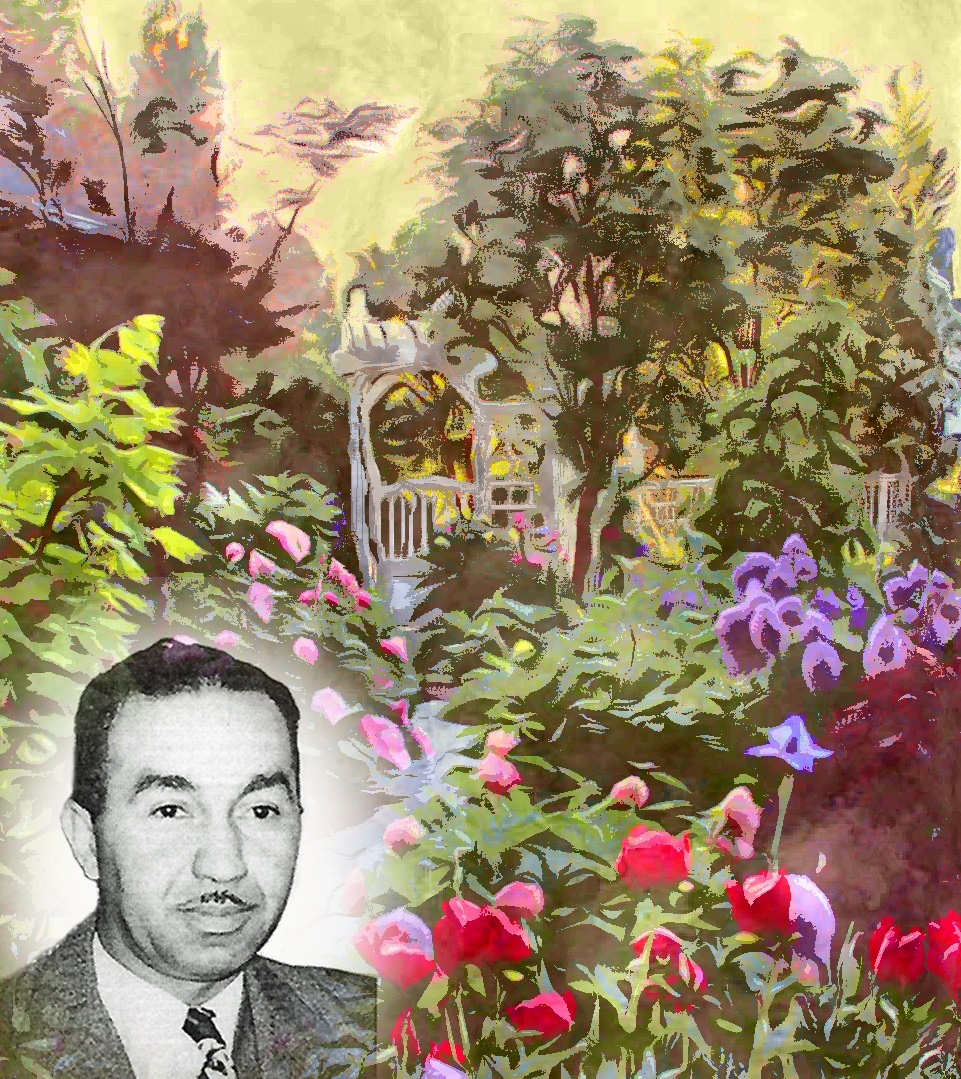

As a professor in the department of agriculture, Dickinson developed a program of courses in landscape architecture, ornamental horticulture, agriculture, floriculture, turfgrass management, and weed science to balance out the school’s curriculum. He planned much of the university’s landscaping, laid out the flower beds throughout the campus, and conducted studies on perennials such as chrysanthemums. The university greenhouses were designed by Dickinson; in them he grew poinsettias, which he gifted to colleagues every holiday season.

Dickinson saw the shortage of landscape architects and the surplus of work as an opportunity for his people.

Plants weren’t just Dickinson’s profession; they were also his hobby. He loved flowers and was an active member of the Men’s Garden Clubs of America, now known as The Gardeners of America. Through his private practice he often helped install gardens for plant lovers and friends at no charge. Dickinson also made regular appearances before garden clubs in Jefferson City, giving hints on better landscaping and plant care as well as hosting a weekly garden program at a local radio station. Beyond the world of horticulture, Dickinson’s talent extended to art. Several of his watercolor drawings were displayed at various places in his native Columbus.

A lasting legacy in and out of the classroom

As a man of the moment, perhaps inspired by crossing paths with American civil rights leaders in his childhood, Dickinson is credited as a trailblazer in changing the interests of students from the popular career choices at the time–medicine, law, and theology–to landscape architecture. He became a vocal advocate for the discipline, and he saw the shortage of landscape architects and the surplus of work as an opportunity for his people.

And Dickinson knew a thing or two about opportunity, because throughout his lifetime it came in abundance. A triple Buckeye, he returned to his alma mater to earn a master’s degree in horticulture and a PhD in floriculture. As one of the few Black landscape architects of his day, he stayed booked and blessed. Dickinson’s services were in such demand that he was able to turn down design work and jobs regularly.

While his landscape architecture classmates and professors may be long forgotten, Dickinson’s legacy will continue to stand solid for generations to come. The Dickinson Research Facility in the College of Agriculture, Environmental, and Human Sciences at Lincoln University is named in his honor. It’s a lasting tribute to a man who demonstrated that haters can be your ultimate motivators.

—Abra Lee is a southern horticulturist and author of the forthcoming book Conquer the Soil: Black America and the Untold Stories of Our Country’s Gardeners, Farmers, and Growers.

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

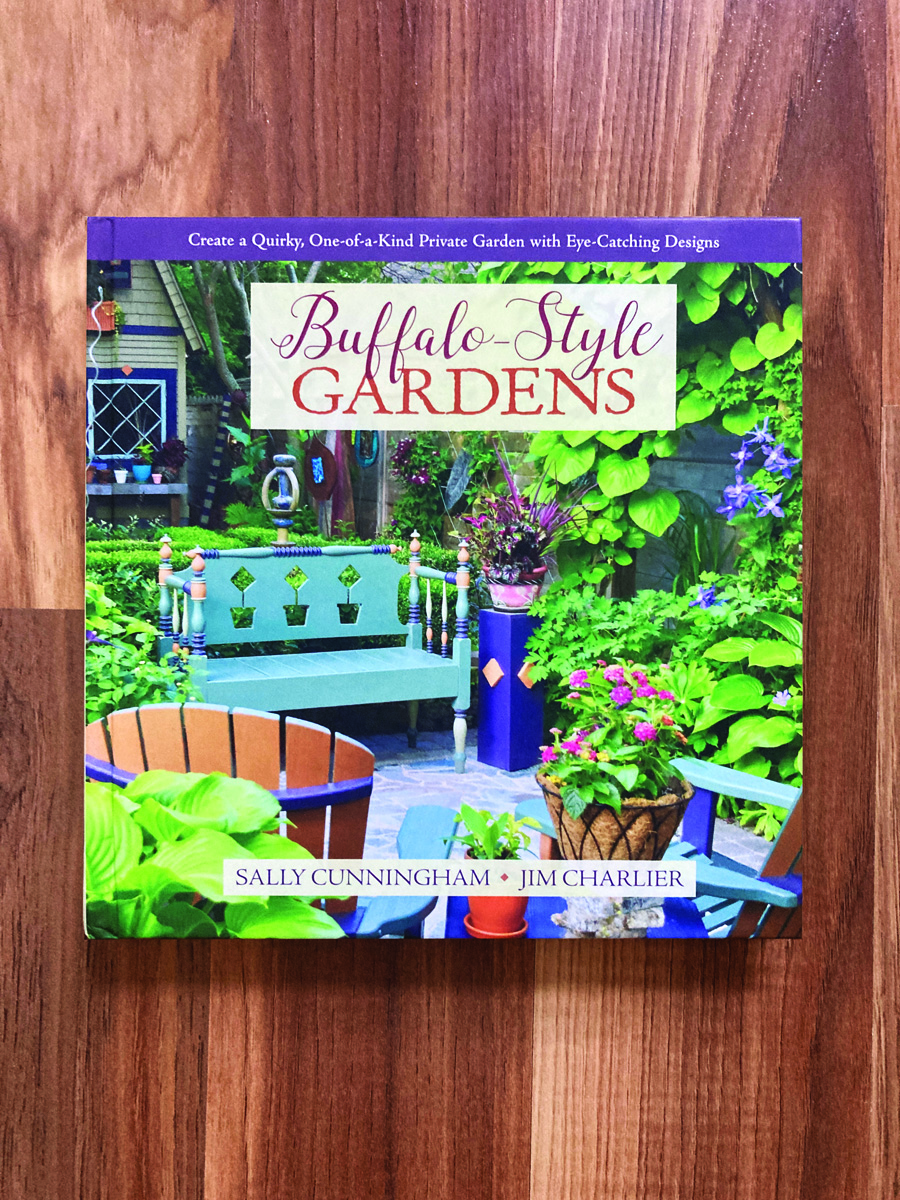

Buffalo-Style Gardens: Create a Quirky, One-of-a-Kind Private Garden with Eye-Catching Designs

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Gardener's Log Book from NYBG

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

When Charles Edgar Dickinson was born on 8 May 1881, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, his father, George Clark Dickinson, was 40 and his mother, Eleanor Lowry, was 27. He had at least 1 daughter with Consuelo Carolina Baillie. He died in 1955, in his hometown, at the age of 74. stumble guys online

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in