As information about growing native plants becomes more available to home gardeners, it’s hard to find a reason not to grow them. I talked to Leslie French about propagating native plants in the Mid-Atlantic. Leslie leads the propagation team at Mt. Cuba Center in Hockessin, Delaware. She explained the benefits of growing natives in the home garden, the best propagation techniques, and her favorite plants to grow.

Advantages of growing natives

Leslie believes that a great advantage of growing natives is the ability to focus on local ecotypes. For example, plants growing in our area are better suited for our climate and adapted to the Piedmont region, where the Mid-Atlantic resides. She refers to renowned local entomologist Doug Tallamy, whose research aims to better understand the ways insects interact with plants and how these interactions create the diversity of ecosystems. Plants that are endemic to this region provide food for insects, which in turn provide food for local species of birds and animals.

In Leslie’s personal experience, she’s seen at least a dozen more species of insects and birds after adding more native plants to her home garden. For example, she recommends pussy willow (Salix discolor, Zones 4–8) as a valuable plant for supporting native wildlife and providing a continuous supply of food and shelter for local species. This willow is one of the season’s first sources of nectar for pollinators after winter.

Different propagation techniques

Many gardeners tend to be a bit intimidated by propagating their own perennials and woody plants, but Leslie advises them to think of propagation as an experiment. If you’re not successful the first time around, do not think of it as a failure.

The various methods of growing your own plants include seed sowing, taking cuttings from existing plants, and dividing plants in the garden. However, since Leslie is a self-proclaimed “seed-aholic,” she loves the diversity of sowing native plants from seed and preserving their genetic diversity that way. Below are some of her tips for keeping the beginning propagator at ease.

Scarification and stratification

Two of the areas of propagation that may be confusing to gardeners are scarification and stratification, methods that can be used to prepare the seed coat for germination. Stratification involves exposing seeds to constant moisture or a cold period for a certain amount of time to help them germinate. Scarification, the process of nicking or damaging the seed coat, can also help speed up germination for some plant species. Leslie’s tip for figuring out if and how a seed needs to be prepared for germination is to pay attention to how the plant grows in nature and do online research. Watch this video to learn more about scarification and stratification. Leslie also recommends books by plantsman and propagator Bill Cullina, who has written many books on native plants.

When sowing seed, there are four main methods: spreading seeds, direct sowing, sowing in raised beds, and sowing in pots.

Spreading seed

The first method is to simply cut off the seed heads in the fall and spread them around the garden randomly. This may appeal to gardeners who don’t mind waiting to see what appears. This method gives nature a little nudge by choosing a general area you want the plants to grow in.

Direct sowing

You can take it a step further by collecting the seeds but directly sowing them where you want them to grow. This is also an easy, low-maintenance way to grow plants. However, the downside of this method is there will not be consistent moisture on the seeds, since they are sown directly in the garden and must compete with other plants.

Sowing in raised beds

A third and (according to Leslie) great way to start propagating seeds is to sow them in raised beds. This method provides a place for germination without competition for water and nutrients. A raised bed is also a way to sow seeds uniformly and keep moisture levels even.

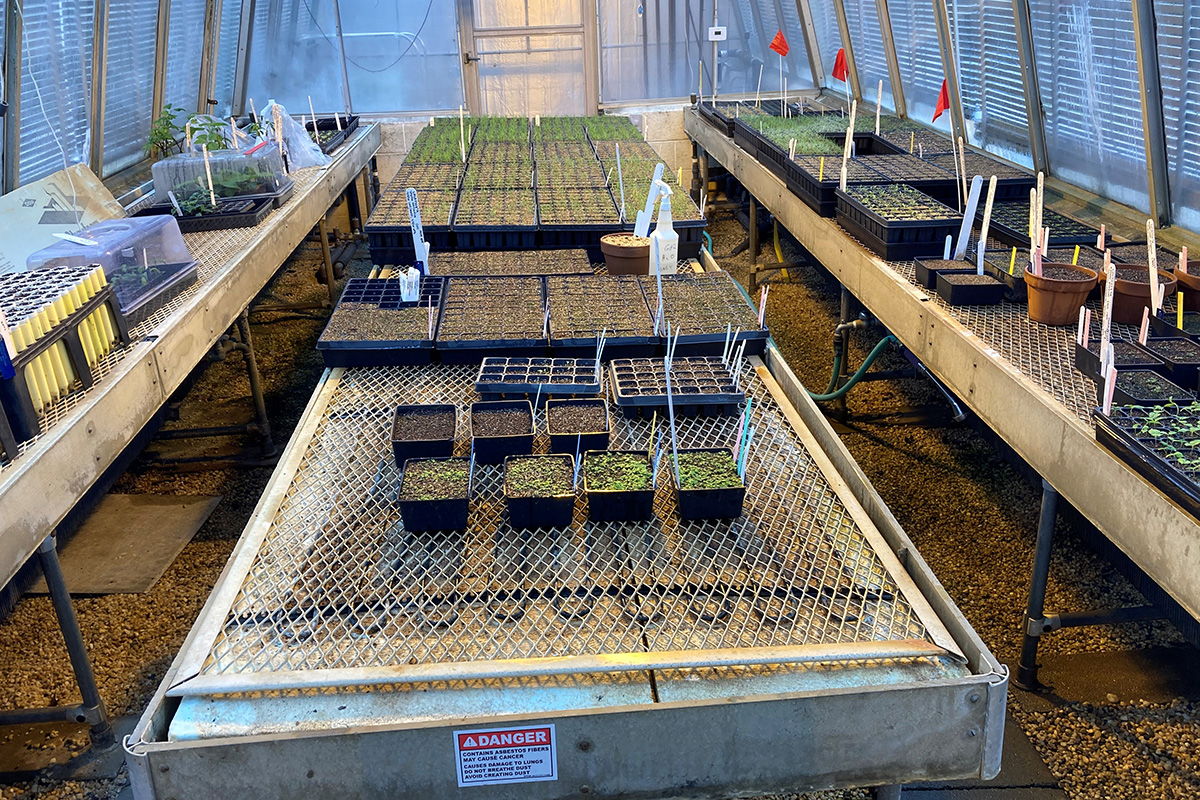

Sowing in pots

The last method Leslie recommends is to start seeds in pots. This way is also great for beginning propagators. This method has the same benefits of using a raised bed; however, the pots may dry out very quickly, so be sure to place them where they will not be forgotten.

Proper care and attention

When setting up a propagation station at home, choose what will work best for you. Also, no matter how the seeds are started, Leslie stresses that moisture and shade from the intense afternoon sun is very important. Although the plant may thrive in full sun at maturity, the cotyledons (embryonic leaves—the first to appear) need to be protected after germination or they will burn in the intense sun.

Favorite natives to propagate

When asked about her favorite plants to propagate, Leslie said that she prefers woody species. She finds satisfaction in seeing a tiny seed grow into a huge shrub or tree.

Hydrangeas

Hydrangeas (Hydrangea spp. and cvs., Zones 4–9) in particular are quite easy to propagate. They have tiny seeds, so they just need to be surface sown or spread over the soil without being covered. Native species of hydrangeas include oakleaf hydrangea (H. quercifolia, Zones 5–9), smooth hydrangea (H. arborescens, Zones 4–9), and silverleaf hydrangea (H. arborescens spp. radiata, Zones 4–9).

Bee balm

Another native genus she recommends trying to grow is bee balm (Monarda spp. and cvs., Zones 4–9). Native species include scarlet bee balm (M. didyma, Zones 4–9), Eastern bee balm (M. bradburiana, Zones 5–8), and dotted bee balm (M. punctata, Zones 3–8). These plants germinate easily outside in the fall. Dotted bee balm is said to need cold treatment, but it also germinates easily when surface sown in warm soil.

Don’t forget grasses

Leslie also highlighted that grasses such as little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium, Zones 2–9) can be sown easily. Little bluestem seed requires stratification, but that can be easily achieved. Simply place the seeds in a bag with a damp paper towel for about month, and germination will occur.

Leslie claims that once a gardener goes down the rabbit hole of growing her own plants, she will never turn back. With these tricks and recommendations, Mid-Atlantic gardeners will be off to a great start growing their own natives. Some great ways to find native plants in your neck of the woods is to look for local nurseries specializing in natives, or local conservation groups that may hold plant sales. In the Delaware and Pennsylvania area, gardeners can check out Delaware Nature Society and Brandywine Conservancy. As for native-plant mail-order nurseries in the region, Leslie recommends Toadshade Wildflower Farm, Sunshine Farm and Gardens, and Izel Plants. Leslie also points out that there are many Midwestern-based native-plant nurseries to choose from. Although Midwestern plants may not be native specifically to our region, it may be fun to try to grow some. So have fun, and happy growing!

Mt. Cuba Center runs a number of exciting trials on native plants to identify the best performers. Learn more about their work in these regional articles:

—Michele Christiano has worked in public gardens for most of her career. She lives in southern Pennsylvania and currently works as an estate gardener maintaining a private Piet Oudolf garden.

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

King Of Spades Nursery Spade

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Razor-Back Potato/Refuse Hook

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Corona® Multi-Purpose Metal Mini Garden Shovel

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in