When I go into the garden first thing in the morning, fuzzy, yellow ducklings race into view. Running around cheeping, they take a bite from the feeder, have a drink from the water dish. They poke their bills into and investigate everything their curious eyes light on. Given their headlong charge across the garden, you would think they had but one day to experience all of life’s miracles.

I love chickens, ducks, and rabbits. I love their chatter, their curiosity, the way they play, and their eagerness to make a home in the garden. Our 62-foot by 166-foot suburban lot is home to several ducks and chickens, plus a couple of rabbits. They are not pets. I like to think of them as garden employees. We don’t name them—they may be dinner. Though well taken care of, they are not coddled. To us they are simply one more piece of the magnificent mechanism that is nature. Such animals, properly managed, can become indispensable tools in the garden, earning their keep and making gardening more efficient and fun.

Chickens, ducks, and rabbits play a pivotal role in fertilizing our garden. First, the poultry have free access to our compost piles. As old bread, vegetable and fruit peelings, fallen fruit, and other waste is discarded, the rabbits and poultry eat much of it, then return it in the form of manure. This considerably speeds up the composting of kitchen scraps. All of the animals’ manure is used in some way to fertilize the garden. The watering tank that provides the ducks a swimming hole is also a handy source of mild liquid fertilizer. Finally, old straw and cedar bedding make terrific mulch, with some free fertilizer in the form of poultry manure thrown in.

This little Eden comes with some cost in time, patience, thought, and a little money. Animals must be fed, watered, housed, and protected from predators. I spend about 15 minutes a day filling feeders, washing and filling water cans, and collecting eggs. Every few weeks, I clean out the duck pond. And a few times a year, there are bigger chores, like grooming the run, replacing the bedding, clipping flight feathers, and scrubbing the chicken coop. If you enjoy animals, however (not to mention fresh, organic eggs), it’s worth the investment. And your garden will thrive.

Getting started

Urban and suburban gardeners should check first with local zoning departments to find out what they can and cannot raise. Codes vary widely regarding types and numbers of animals permitted. Some municipalities allow no animals at all. I also recommend investing in a handbook on raising these animals. You’ll learn a lot more than I can tell you here.

|

|

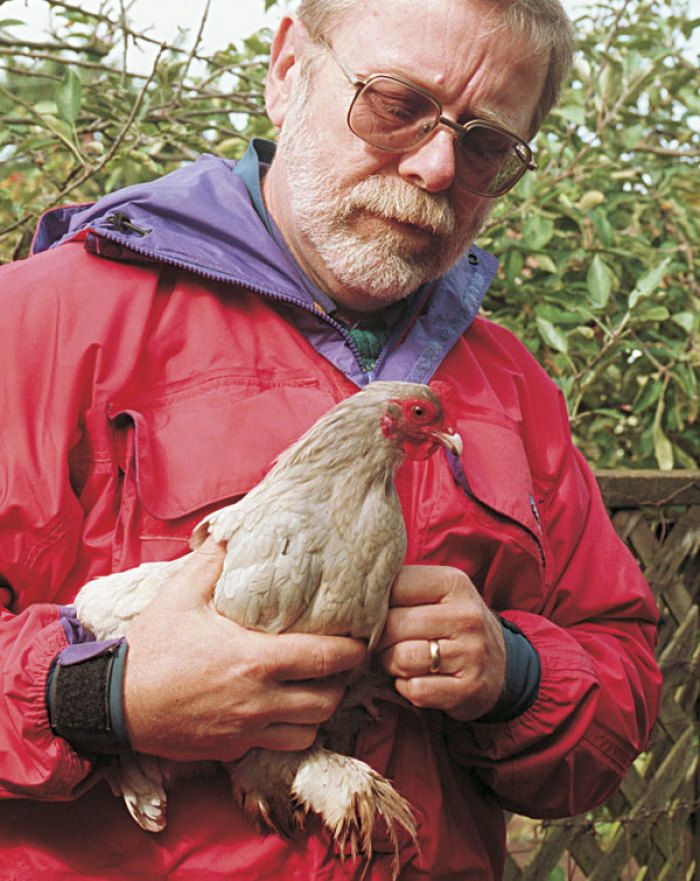

| The author with a Bantam chicken. | |

To be sure you’re getting healthy animals, buy chicks, ducklings, and young bunnies only from a reliable dealer. Chicks and ducklings are available as hatchlings from feed stores, which will sell in small quantities. There are mail-order sources too, but they have higher minimums.

As for equipment, you’ll need an incandescent bulb for keeping the chicks and ducklings warm, a bin and tray feeders, and waterers. At first you’ll need chick starter feed, and after that, an 80-pound bag of triple-duty or general-purpose feed will take care of six chickens for about a month if they are also fed with garden and kitchen scraps. You can build a coop for little or nothing using recycled lumber, but buy the best wire fencing you can afford, to ensure that your animals don’t get out or predators get in.

If you’re interested in rabbits only for their droppings, you can probably find bunnies for free through feed stores, kennels, or a veterinarian’s office. On the other hand, if you want to raise rabbits, a good pair of breeders will cost more than $100. They are worth the money, however, because they live longer and will have larger, healthier litters. Buy your rabbits at two to three months old. Contact your local extension service for sources.

You’ll also need wire cages for housing rabbits. A hutch to hold the cages and provide shelter from weather can be assembled cheaply from recycled wood, and you’ll have to get a food bin and waterer. A 50-pound bag of rabbit chow will feed two rabbits for about three months, if you add in garden and kitchen scraps.

Animal housing and other considerations

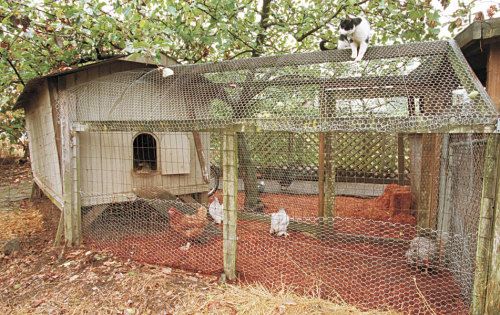

Chickens need shelter from rain and drafts, a dark place to lay eggs, a roost (a stout 2- to 3-inch-diameter branch or dowel), and at least 2 to 3 square feet of floor space per bird. A fenced perimeter with fencing over the top keeps poultry in and predators out. Three hens are enough of a flock to process kitchen scraps, patrol for weeds and insects, and produce eggs. Roosters are noisy and aren’t needed for eggs.

|

| Chickens need to spend nights in a coop where they can roost and lay eggs. During the day, they take the air in a fenced run. (Frank, the cat, considers it his special duty to guard the poultry.) |

I prefer Bantam breeds, which are a fifth to a third as big as full-size chickens. Bantams eat only 20 to 25 pounds of feed per year, they’re much easier to handle than full-size chickens, and they do less damage if they escape into the garden. Avoid show breeds, especially those with long feathers, because in a garden environment they’ll get muddy in a hurry.

Ducks are more tolerant of rain, wind, and cold than chickens, but they still need shelter, which allows them privacy for laying. Ducks are happier with a small pond for swimming, playing, and mating. I use a 4½-foot-diameter galvanized stock watering tank. I rigged an 8-foot ramp from a long board with scrap ½-inch-grid hardware cloth stapled to the top for traction. Raising ducklings is very similar to raising chicks, except no roost is needed.

|

|

|

| Muscovy ducks don’t quack much, and they don’t swim as much as other duck breeds. Both traits make them a good choice for suburban gardens. | A large shallow dish makes a great kiddie pool for Muscovy ducklings, which can’t float or swim well until their oil glands develop. | |

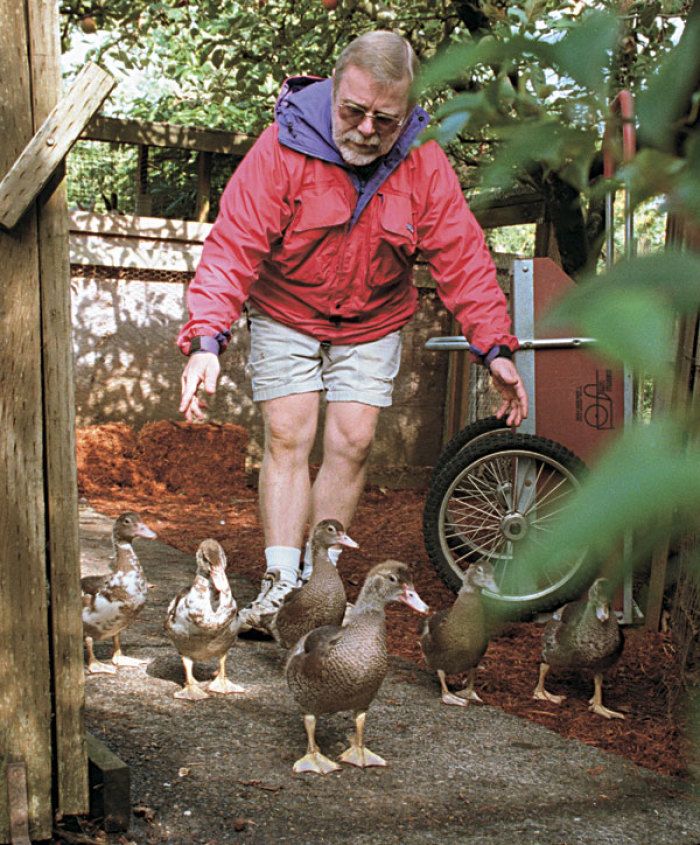

After raising many kinds of ducks, I prefer Muscovies. They’re calm, and since they don’t quack, they’re quiet, which makes them ideal for urban settings. Muscovies aren’t the greatest layers, though. If you want duck eggs, try Indian Runners.

|

|

| Rabbits are housed right over the compost piles (right), for automatic blending of manure with kitchen and garden refuse. A roof with a wide overhang keeps out rain and sun. In winter, plastic curtains can be lowered to keep out the wind. | |

|

|

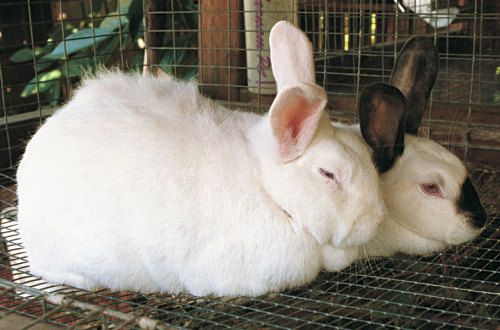

| This pair of New Zealand rabbits is sharing living quarters in hopes of starting a family. A successful outcome is pretty much guaranteed. | |

Rabbits are very hardy, but they don’t like to get wet. I prefer to shelter each in a large wire cage (30 inches by 36 inches by 18 inches) in a hutch conveniently located above the compost piles. A broad roof shelters the rabbits from the rain, and in winter I can unroll a plastic skirt around the cages to keep out wind and snow. I use three cages—one for the buck, one for the doe, and one for growing out the young (called kits). If I were keeping rabbits solely for their compost benefit, I’d have one adult rabbit per cage. Each cage needs a feeder and a waterer. The doe’s cage also has a nesting box where she keeps the young warm until they’re weaned. The buck and doe should share a cage only during mating.

I keep New Zealand rabbits, which reach 9 to 12 pounds and are white, black, or red. Rabbits are quiet, inexpensive to keep, and take little room. They eagerly eat blackberry canes and quack grass, two perennial weeds I don’t like to compost for fear of spreading them. It gives me great satisfaction to recycle these plant pests into cute personalities and rich manure.

My Zone 8 garden is blessed with a maritime climate, meaning we have relatively mild winters and summers. Temperatures seldom go below 20°F or above 100°F. Readers living in areas with extreme weather should check with their local extension service to confirm minimum requirements for housing.

Ducks and chickens need room to roam

In the 18 years that I’ve been keeping these small animals, I’ve learned that it pays to keep them happy. Happy animals are healthier and live longer than stressed animals.

While poultry need room to wander, don’t leave them permanently in the garden because they can do damage to plants, foul patios and decks, and destroy raised beds. Therefore, you need a poultry run. At a minimum, the run needs to provide shelter from sun, rain, and wind, and it should be on a well-drained site.

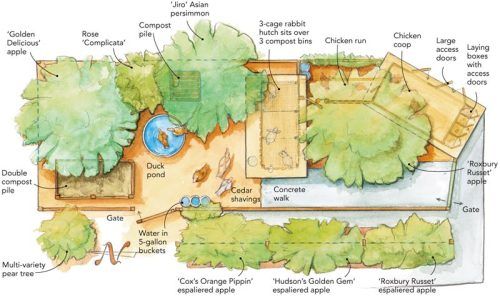

Our run is about 16 feet by 44 feet (see the site plan at the end of this article). It is planted with fruit trees, shrubs, and vines to provide the animals with privacy, food, and shelter from weather. Our compost piles are there too, for easy mixing of manure with other raw materials.

I keep the ground in the run covered in cedar shavings, which keeps mites and flies down and smells good. I replace the cedar every few months. I also replace the straw in the chicken coop twice yearly, once in early fall and again at winter’s end.

In the fall, I lay the straw down in thick pads, separated from a bale but not shaken loose. Over the winter, when the birds spend a lot of time indoors, they keep busy picking the straw pads apart, hunting for weed seeds. Since I’ve been doing this, my chickens seem a lot happier, and they don’t pick on each other as much.

|

|

| Like recess for school kids, supervised garden time provides these youngsters with the chance to have fun—and get into mischief. Ducks will hunt busily for slugs, insects, weeds, and strawberries. | |

Because ducks can be rounded up and herded back into the run relatively easily, we let them out on supervised forays into the garden, where they hunt for slugs, slug eggs, insect larvae, and weeds. We do this as often as it’s convenient for us, but not before putting out small corrals of anchored fencing to protect precious or vulnerable plants. Ducks are especially fond of tender greens and ripening strawberries.

Harvesting the goodies

In return for our investment in time and money, we get more than eggs. There’s a big payoff in manure. There are several ways of using this precious commodity. As mentioned before, the rabbit manure falls through the cage floors and automatically mixes with the compost below. You could instead put the droppings right into growing beds, or make manure tea.

I use spent poultry bedding from the chicken coop—a mix of straw and bird droppings—as a fast-draining covering for my garden’s dirt paths. The bedding keeps our feet dry, looks good, and feeds plants as it rots. About three times a year, I peel up soiled cedar shavings from the run and spread them on beds as mulch or on the paths, just as I do with the straw.

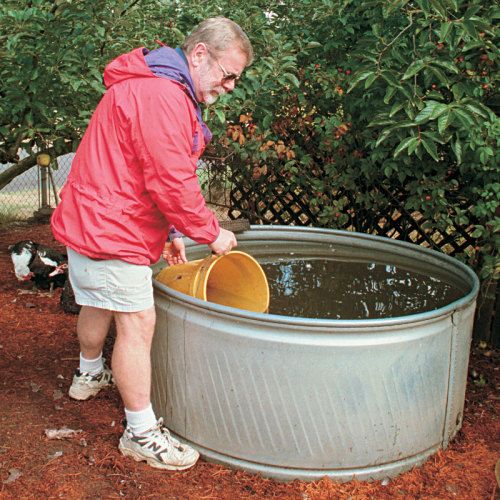

The stock tank, which serves as the duck pond, provides a rich, dark soup of droppings, feathers, and chewed weeds. I clean the pond every two weeks or so in summer, and about every six weeks in winter. Sometimes I bail it out with 5-gallon buckets, which I empty around the garden as needed. An easier way is to use a hoe to open a shallow ditch running from the drain spigot on the tank to the garden, and then open the drain. Once the water is gone, there’s a rich sludge left in the bottom of the tank. In winter, I apply this directly to the garden. During the growing season, I dilute it and sprinkle it around the beds.

|

|

|

| Spent cedar shavings from the poultry run find new life as mulch for garden paths. Rains gradually leach the manure down into the root zone of nearby plants. | The duck pond (this one is a stock tank) is a good source of liquid fertilizer. The author refreshes the water every couple of weeks in summer, and every six weeks in winter. | |

If you’re not interested in harvesting an occasional animal to eat, you can keep only females to prevent breeding. However, eventually, you’ll have to deal with a sick or dying animal. Injured animals should heal quickly with proper care. Consult a handbook or your vet ahead of time so you’ll be prepared. We have decapitated a dying animal to ease its suffering.

The intangible benefits are nice too

Other good stuff happens as a result of keeping animals. Squatting to inspect a tomato plant will often convene a committee of ducklings standing on or between my feet. They will look from me to the tomatoes and back again, eagerly posing chirped questions I can only guess at. I love their cheery little voices and their permanent smiles. Frank, the cat, is fascinated by the poultry and considers them his special watch. He guards the birds from the rabbit hutch roof or from his favorite limb in the persimmon tree.

Years ago, I set an old mirror in the run for the birds’ amusement. The ducks were wary for a couple of days, then they gradually began to approach this new object to check it out. You could see their feathers ruffle as they glared at the intruders they saw. Eventually, one duck, a Khaki Campbell, struck up quite a romance with his new “friend,” whom he fiercely defended whenever another duck approached.

Hand feeding ducklings is great fun because they’ll jump into your palm as if on springs. One warm day while I was in the kitchen with the back door open, I heard such a cheep! I saw a single duckling standing at the open door, neck and stubby wings extended, cheeping as loudly as he could. He entered the room, still talking away. He waited until I had filled a can with feed, then tumbled down the steps to wait for me with his hungry siblings.

Morning feeding time, returns from vacation, and pond cleaning day will find our ducks running in circles on their toes in celebration. All this makes these little strawberry vandals more than welcome here.

This article originally appeared in Kitchen Gardener #28 (August 2000).

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

Gardena 3103 Combisystem 12-Inch To 20-Inch Adjustable Metal Fan Rake Head

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Fort Vee - Organic Potting Soil Mix

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Bonide Captain Jack's Neem Oil, 32 oz Ready-to-Use Spray, Multi-Purpose Fungicide, Insecticide and Miticide for Organic Gardening

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in