The Science Behind Plant Division

Understanding how and why a plant reacts to dividing may help you achieve greater success

Divide to multiply. Even the language of this common garden practice hints at its paradoxical power. Division is a simple method of vegetative propagation that involves separating a perennial plant into two or more pieces. Not only is it the easiest way to get more plants, but also it is required maintenance on some perennials if you want maximum bloom year after year—and who doesn’t? Division is practical, relatively easy, and oh-so-gratifying. After a successful division, a gardener stands a little taller in her boots.

Sometimes I am satisfied to just bask in the miracles of plant growth in my garden. But when one of my actions—such as dividing—results in a dead or declining plant, the scientist in me wants to know why. Plants are complex living organisms, and the more I understand the science of their structures and growth cycles, the better gardener I become. Successful division hinges on the growth of new roots, and mastering division of any plant begins with a practice that’s at the heart of science—careful observation of your subject and its environment.

Before You Divide, Ask Yourself Two Questions

To understand what happens to your plants—the good, the bad, and the ugly—during division, you first need to figure out what type of plant you’ve got and what time of year you’re dividing it.

1. What type of root-and-crown system does it have?

Exactly how you divide—or not—depends on understanding what’s underground. Dig up a perennial and you will find some form of the following five types of root/crown systems. As you consider how to proceed, keep in mind that each plant division must contain at least one bud (eye) or growing point as well as a few healthy roots.

Clumpers (often with fibrous root systems)

These divisions are sometimes referred to as offsets. Many smaller plants grow from the base of the original plant, each offset forming its own separate root system. This often makes for easy hand division with very little tissue damage as you wiggle and tug to separate the individual growths.

Examples

1. Lambs’ ears (Stachys byzantina and cvs., USDA Hardiness Zones 4–8)

2. Daylily (Hemerocallis spp. and cvs., Zones 3–9)

3. Hosta (Hosta spp. and cvs., Zones 3–9)

|

|

|

Runners (with thin rhizomes and/or stolons)

These plants tend to be spreaders, covering the ground by shallow horizontal stems called rhizomes. Rhizomes root along their nodes and then promptly send up new shoots, a characteristic that results in many dividable units.

Examples

1. Bee balm (Monarda spp. and cvs., Zones 3–9)

2. Aromatic aster (Symphyotrichum oblongifolium and cvs., Zones 3–8)

3. Goldenrod (Solidago spp. and cvs., Zones 4–9)

|

|

|

Tight, woody crowns (often with fairly thick roots)

We’re moving into more challenging territory here, where buds are tightly packed on a hardened crown (base). Achieving divisions that include several buds and a mass of healthy roots requires an older plant. It should be large enough to divide into 3 to 4 pieces before taking the risk of cutting through the brittle crown.

Examples

1. Baptisia (Baptisia spp. and cvs., Zones 3–9)

2. Bluestar (Amsonia spp. and cvs., Zones 3–9)

3. Peony (Paeonia spp and cvs., Zones 4–8)

|

|

|

Thick rhizomes or tubers

These organs are technically stems, growing along or underneath the ground and are thick and fleshy, modified for food storage. A knife or pruners are perfect for slicing into sections, each containing at least one bud (eye).

Examples

1. Bearded iris (Iris spp. and cvs., Zones 3–10)

2. Canna (Canna spp. and cvs., Zones 7–11)

3. Dahlia (Dahlia spp. and cvs., Zones 8–11)

|

|

|

Single taproots and woody shrublike perennials

My advice on these? Leave them be. Shrublike perennials such as lavender (Lavandula spp. and cvs., Zones 4–9) and Russian sage (Perovskia atriplicifolia and cvs., Zones 4–9) develop single woody bases that are not amenable to splitting. Single taproots, like those of butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa and cvs., Zones 3–9) are equally undividable. With time, these may form multiple taproots and the brave gardener may attempt separating these in early spring.

2. What time of year is it?

Temperate-zone plants are keenly attuned to predictable seasonal changes. Changes in day length and temperature influence hormones that direct critical cycles, such as shoot growth, flowering, and, most important for would-be dividers, root growth. Most perennials grow vigorous new roots as the soil begins to warm in early spring. Many also grow new roots in autumn, when the soil is still warm but stems and leaves are going dormant. Because successful division depends on establishing new roots, it’s easy to see why spring and fall are the recommended times.

Some perennials will grow roots in summer if disturbed, but high temperatures demand evaporative cooling of leaves, which leads to water loss. Essential water loss at the same time you have just temporarily removed a plant’s water uptake system (i.e., the roots) adds up to one stressed perennial. You’ll need to do a little research to find out if your particular species has a preference for fall or spring division. For instance, many ornamental grasses only grow new roots in spring. If you divide these grasses in fall, they enter winter with old, damaged roots that cannot effectively rehydrate the plant and are vulnerable to winter rot. Without healthy new roots, the division will likely fail.

Basic plant division step-by-step

Now that you understand your plant’s structure and seasonal growth patterns, grab a spade and dig in. When you do, a lot is happens to your plant at the cellular level—which can affect your dividing success or failure rate.

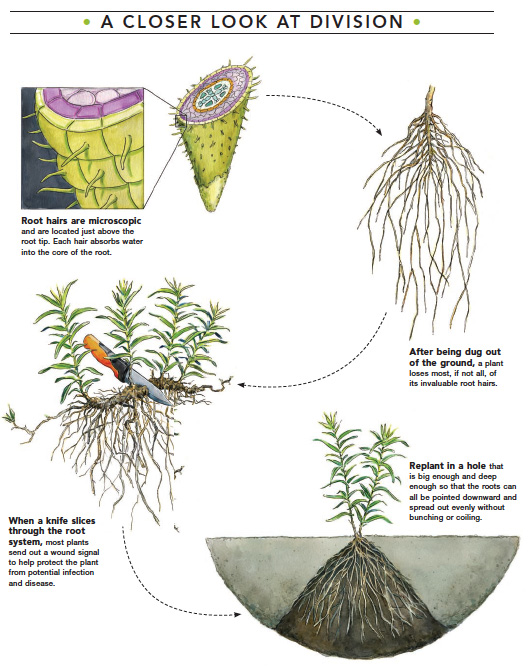

Step 1: Carefully dig out the plant

Keep the unearthed plant shaded from the sun and protect the roots from exposure to drying air if it’s not going to be replanted immediately. Removing the plant from the ground destroys almost all of its tiny, delicate root hairs. These hairs grow from the outer cellular layer (epidermis) of the younger roots and are responsible for the majority of water uptake. Protecting the unearthed younger roots from further damage by desiccation means a faster recovery once the division is replanted. The replanted root systems have to restart the cell division process (growing new root tips and root hairs) before water uptake can begin again.

Step 2: Separate your plant into pieces

Make sure each piece contains several buds or growth points. The number of buds per division and whether you use your hands or a blade depends on the type of root system. Clumpers can be separated by teasing and tugging with your hands or slicing with a clean knife if the clump is especially tight. Runners are best divided with a knife, pruners, a spade, or forks. Thick rhizomes and tubers as well as tight woody crowns require a sharp knife or pruners. Woody crowns may require a hand saw or sharpened spade.

You are going to damage some roots and rhizomes, but there is no need to fret.At the first bite of spade or knife, the plant releases wound signals and mobilizes resources to healthy roots to internally protect exposed areas from infection. You can help by making clean cuts and removing shriveled, dead, or ragged pieces. Most cut roots do not “bleed,” so you don’t need to worry about excessive moisture loss, the exception being latex-producing plants like euphorbias (Euphorbia spp. and cvs., Zones 3–10) and poppies (Papaver spp. and cvs., Zones 3–9). They will leak milky or colored sap and can be placed in warm water temporarily before planting to reduce the bleeding.

Step 3: Replant, taking care to dig your hole wide enough

Roots want to grow out and down, so don’t attempt to squeeze them in a hole by allowing the tips to point up or by contorting and winding them around the planting hole. That can lead to the plant expending valuable energy trying to straighten its roots out. Be sure that the soil is in good contact with the root system by firming it in. This assures that when tiny new root hairs begin to grow, they will hit soil and water rather than pockets of air. Water in slowly and thoroughly, allowing the soil to settle further against the roots. Doing this will ensure happy divisions, which, in turn, ensures happy gardeners.

For more on plant division, check out Why Plant Division Fails, and How to Ensure Success.

Paula Gross is the associate director of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte Botanical Gardens. Illustrations by Elara Tanguy.

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

Gardzen 3-Pack 72 Gallons Garden Bag

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

ARS Telescoping Long Reach Pruner

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

SHOWA Atlas 370B Nitrile Palm Coating Gloves, Black, Medium (Pack of 12 Pairs)

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in