Drive down any suburban street across the country, and you’re likely to see the same old thing: lawn, lawn, lawn, spruce tree, lawn. This would be a dream come true for early landscape architects, like Frederick Law Olmsted, who saw a nonstop sea of grass as a way to bind houses together in a parklike setting. Since those early days, the lawn has been seen as a way of establishing an instant relationship with the neighbors—a relationship built on our mingling turfs. A nice lawn can be a beautiful thing, but if you are a gardener, like our friend Faye Beck, this monotony is not a dream but a nightmare.

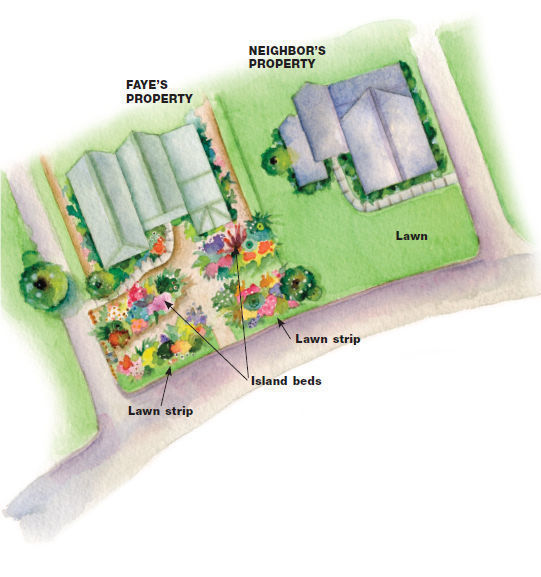

Set your site apart: Although Faye and her neighbor own lots that are similar in size and shape, Faye’s front yard undeniably stands out. Irregularly shaped garden beds fill most of the space, although a few patches of grass remain to visually connect her property to the property next door.

Most gardeners want an exuberant front yard that is overflowing with plants. This, unfortunately, would surely make their landscape stick out like a sore thumb from their neighbors’. So how can gardeners set their residence apart without making it look like a rowdy front-yard circus with no connection to its surroundings? Faye’s 5,000-square-foot garden is the perfect example of a successful design that embraces the middle ground. By using three specific strategies, Faye formed a unique front-yard landscape that manages to say, “Yes, a gardener does live here—but I still fit in.”

Keep just enough grass for effect

Tired of looking at and caring for her high-maintenance front lawn, Faye decided to install several garden beds. During their installation, she wanted to get rid of the lawn completely. But ripping out all of the turf was too drastic and would have put her front landscape at odds with the rest of the neighborhood. Faye, instead, left a few areas of grass along her front curb and along the property lines she shares with neighbors. These grassy spots help maintain a connection to the surrounding homes and are easily mowed with a string trimmer.

Turf plays a small but important role. Because most of the neighborhood has a traditional front lawn, keeping a little grass along the edge of the garden beds was crucial so that this property didn’t seem foreign in its surroundings.

The best part for Faye is that the lawn sections are visible only from the street. She doesn’t have to look at them from her front door, but passersby on the street think that there are more areas of turf beyond the eye’s reach. This makes Faye’s yard seem less out of place in her turf-heavy neighborhood. As a bonus, Faye no longer needs to worry about fighting lawn weeds or diseases. She even plans to replace the remaining patches of turf with dwarf mondo grass (Ophiopogon japonicus ‘Nana’, USDA Hardiness Zones 7–10), which will look like lawn but will not have to be mowed, fertilized, or treated with herbicides.

Forget about straight lines. When designing a small space, curved beds make a garden seem large and, in turn, full. This planting, which stretches between the front walkway and the house foundation, doesn’t appear to end when it is actually only 25 feet long.

Irregularly shaped beds give the illusion of more space

Lawns, like the ones all her neighbors have, generally feel and look spacious, so Faye needed to avoid creating a garden that looked and felt claustrophobic. She initially built long, traditional borders in her front yard but then decided to slowly expand them into irregularly shaped, slightly bermed islands. Expanding the beds not only provided room for more plants but also gave the front yard a greater sense of space. Straight lines tell the eye to stop, whereas curved lines trick the eye into thinking that the expanse goes on indefinitely. To give the beds distinct edges, which can sometimes be a challenge with curved beds, Faye used fieldstone and river rock.

Although Faye’s front garden is only 5,000 square feet, visitors are always amazed by the variety of views they experience while traveling the paths between her beds. Everywhere you look, you try to anticipate what Faye has hidden around the deliberate curves. The nonlinear shapes of the beds also lend a sense of informality to the garden, allowing Faye an almost limitless plant palette. Placing large plants in the middle of the beds—instead of off to one side—allows visitors to enjoy them from every angle because they must walk around the perimeter to take it all in.

Color helps move the eye. Plants with similar hues, like this black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia cv., Zones 3–11), coleus (Solenostemon scutellarioides cv., Zone 11), and ‘Fireworks’ fountain grass (Pennisetum ‘Fireworks’, Zones 9–10), give a design fluidity.

Plant in blocks of color

Being a savvy gardener, Faye created a mixed garden by filling in her beds with a little of everything: dwarf conifers, trees, shrubs, ornamental grasses, perennials, tropicals, bulbs, and annuals. But her approach to blending different plant materials together was guided by color. As she slowly extended the footprint of her beds, she selected companions that would allow her to create drifts of color. If, for instance, a canna (Canna spp. and cvs., Zones 8–11) were firmly established in a bed, she selected a companion that possessed one of the canna-leaf hues. Then she isolated a different color aspect of the companion plant to find a buddy for it, planting the buddy to one side.

This method of combining plants created waves of colors in Faye’s garden that help move the eye from one area to the next and give the front garden a sense of continuity. Every part of a plant is fair game for color matching: leaves, seed heads, flowers, and even emerging growth or fading blossoms. Faye points out, however, that you can’t just combine plants that look great together; they have to share the same cultural requirements.

As visitors pass by Faye’s front yard, they know instantly that a gardener lives on the property. And although it is not the typical landscape in her neighborhood, it still belongs, which makes Faye—and her neighbors—happy.

Connect the colors

With thousands of plants to choose from, we wondered how Faye selected the ones for her beds. Her process involved, first, picking a focal plant, then creating waves of color echoes based on that plant. Here’s how the process works:

➊ ‘Australia’ canna (Canna ‘Australia’, Zones 8–11)

This canna is the starter plant—a towering clump that is the main focal point of the bed.

➋ ‘Religious Radish’ coleus (Solenostemon scutellarioides ‘Religious Radish’, Zone 11)

The bright red tip of the coleus leaves perfectly matches the flowers of the nearby canna.

➌ ‘Tomato Soup’ coneflower (Echinacea ‘Tomato Soup’, Zones 4–9)

The center cones of these blossoms echo the deep burgundy of the canna leaves.

➍ ‘Flamenco Samba’ cuphea (Cuphea llavea ‘Flamenco Samba’, Zones 8–10)

This cuphea is a self-sower that surrounds the coneflower, and its blossom color is just a shade lighter than that of ‘Tomato Soup’.

➎ Margaritaville™ yucca (Yucca recurvifolia ‘Hinvargas’, Zones 7–11)

Drawing inspiration from the vibrant green foliage of the cuphea, Faye planted a variegated yucca next to it because of its distinctive green leaf margin.

➏ ‘Dwarf Bright Gold’ Japanese yew (Taxus cuspidata* ‘Dwarf Bright Gold’, Zones 5–7)

The golden needles of this conifer complement the subtle yellow tones of the yucca blades.

➐ ‘Solfatare’ crocosmia (Crocosmia ‘Solfatare’, Zones 6–9)

When in bloom, the honey-colored flowers of this perennial are even more eye-catching with the golden-leaved yew as a backdrop.

➑ Leatherleaf sedge (Carex buchananii, Zones 6–9)

The brown leatherleaf sedge picks up the smoky bronze tones of the sword-shaped crocosmia leaves.

Make the space exciting but not peculiar. The goal of creating a distinctive front garden is for it to look like the colorful cousin of the neighborhood. The garden should relate to the community as a whole without abandoning any of the garden’s flair.

To identify many of the plants shown in this article, visit FineGardening.com/extras.

Sue Hamilton is an associate professor of horticulture at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville and director of the University of Tennessee Gardens. Andy Pulte is an arborist and horticulture instructor at the University of Tennessee.

Photos: Danielle Sherry. Illustration: Grace S. McEnaney

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in