Once we understand some of the concepts of naturalistic design, questions of a more practical nature tend to pop up. We reached out to landscape architect Thomas Rainer and garden designer Piet Oudolf to get some answers.

Q: Can a naturalistic garden be done on a smaller scale?

Thomas Rainer: The tools for making a naturalistic garden—layering compatible species one on top of another—are ideal for small-space gardens. When you have limited room, there’s so much pressure for each plant to look good for as long as possible. This is often why so many suburban gardens rely on gaudy meatballs that never change. With naturalistic layering, you can literally get more flowers out of a small space by layering dynamic plants on top of each other (see below).

Imagine this seasonal planting with wave after wave of color

March

April

May

June

July

August

Fall

Q: Much of the matrix seems to be made up of grasses. Does this leave a gap in interest while they bulk up?

Piet Oudolf: Grasses that are used as a matrix are not late developing. Use plants like sedges and moor grass and other grass species that are already present in early spring. Filling up temporary gaps left by late-developing grasses can be done, but the plants will probably die when they are covered later in the year. A good matrix is closed like a carpet. Spring ephemerals, however, will survive because they go dormant in summer.

r

Q: During the planting phase, which should we put in first—the matrix plants or the primary and scatter plants?

PO: Planting order is important. If you set out the primary plants and scatter plants first, it makes it easier. You can then fill in the open space with the matrix. When you first set out the matrix, it is more complicated to fill in with the individuals if you want to make changes.

Q: What advice do you have for someone who would like to adapt an existing bed to a designed plant community?

TR: It’s easy to convert existing beds as long as you match plants to the site conditions. Is it a hot, dry, and stressful area? Stick with stress-tolerant plants such as muhly grass (Muhlenbergia spp., Zones 5–9) or ‘Little Rascal’ sulphur buckwheat (Eriogonum allenii ‘Little Rascal’, Zones 5–9). Is your bed full of moist, rich soil? That is ideal for competitive plants such as switchgrass (Panicum virgatum and cvs., Zones 3–9) or giant coneflower (Rudbeckia maxima, Zones 4–9). Is your bed frequently disturbed, like a hell strip along a sidewalk? Try ruderal self-sowing species that will be activated by the disturbance, such as wild petunia (Ruellia humilis, Zones 4–8) or columbine (Aquilegia canadensis and cvs., Zones 3–9). When you match the plant community to the site condition, it’s easy to adapt.

Q: Plants in a designed plant community will knit together to keep weeds down. What do you do before they have time to grow together?

TR: We mulch with a thin layer of quick decomposing mulch: leaf mold in shady situations, compost in average soil, or even fine gravels in hot, sunny sites prior to planting. Then we plant into that mulch. If you plant at the right times in spring or fall, that density typically closes within a few months. It’s a method designed to minimize weeding.

Q: Approximately how much of a planting should consist of matrix plants?

PO: The percentages for a matrix range from at least 30% up to 50%, depending on the diversity you intend to bring in.

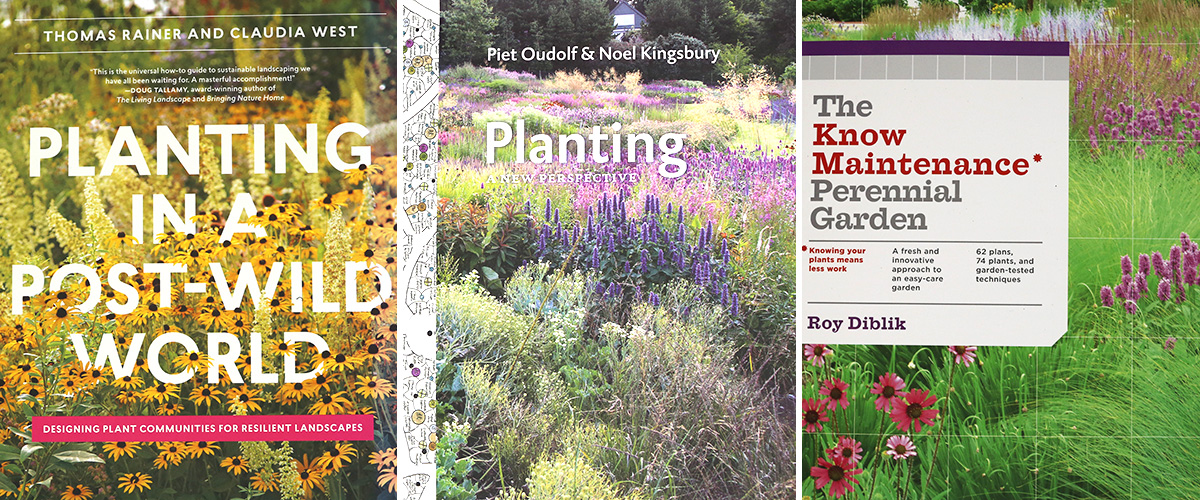

For further reading

There is much more to naturalistic garden design than will fit in one article. If you would like to read more about the topic, here are some options.

Planting in a Post-Wild World: Designing Plant Communities for Resilient Landscapes

by Thomas Rainer and Claudia West

Planting: A New Perspective

by Piet Oudolf and Noel Kingsbury

The Know Maintenance Perennial Garden

by Roy Diblik

More on naturalistic gardens:

- A Naturalistic Garden Is Better for the Environment and Requires Less Work

- Plants for a Matrix-Style Garden

- Plants for a Layered-Style Garden

Steve Aitken is editor at large.

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

A.M. Leonard Deluxe Soil Knife & Leather Sheath Combo

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Thanks

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in