It’s easy to understand why gardeners love viburnums (Viburnum spp. and cvs., USDA Hardiness Zones 2–9). They have lustrous leaves and large (sometimes fragrant) blossoms, and many produce magnificent berries or display outstanding fall color. With traits like these, there is seldom a time that these shrubs aren’t looking good at the nursery—and that’s why so many of us ending up buying one.

But there are drawbacks to these wonder shrubs: Quite a few are prone to diseases, some struggle with their hardiness, and others can require well-timed pruning. If you already have a viburnum, chances are you might want to know why it’s not doing so great, and if you don’t have one, you want to make sure to select one that is trouble-free. The editors of Fine Gardening asked experts from across the country to answer common questions regarding viburnums and to shed some light on this popular yet beguiling group of plants. Don’t invest in one of these shrubs (or rip one out from frustration) until you’ve read what these experts have to say.

How do I get rid of aphids and viburnum leaf beetles on my shrubs?

Daniel Gilrein replies: Aphids and viburnum leaf beetles are the most damaging pests that can plague a viburnum. To get rid of them, you’ll need to know their life cycles.

The snowball aphid starts life as an egg that is laid on or around the buds of viburnums in fall. The eggs hatch as the buds open in spring, and the young aphids begin feeding on the new growth. Within a few weeks, the stems and leaves become twisted and curled, with dusty grayish aphids hiding out within the bunched growth (photo above). You can use horticultural oils or insecticidal soaps during the plant’s dormant stage in spring or soon after bud break to control the aphids and prevent damage. Damaged growth can also be pruned off. Though it can be disfiguring, plants typically survive an aphid attack. Natural enemies, such as lady beetles or syrphid fly larvae, will often intervene to feed on the aphids, so you can also opt to just let nature take its course. Some viburnum species, such as the much-loved doublefile viburnum (V. plicatum f. tomentosum, Zones 4–8), show some aphid resistance.

The viburnum leaf beetle is a small, grayish brown insect that skeletonizes the foliage of viburnums. Defoliation of some species can be severe, not only spoiling their appearance but also eventually killing the plants. Eggs are laid into small cavities excavated into the bark of the viburnum twigs. You may be able to identify where the insects are by looking for buds that are failing to expand. Eggs hatch about midspring, and the larvae begin feeding on foliage. By late spring, the larvae descend to pupate in the soil; adults appear in early summer and continue the damage. Some viburnums—including Koreanspice viburnum (V. carlesii, Zones 5–8), Burkwood viburnum (V. burkwoodii, Zones 5–8), doublefile viburnum, Judd viburnum (V. juddii, Zones 5–9), and leatherleaf viburnum (V. rhytidophyllum, Zones 6–8)—are, fortunately, resistant to the beetles. You can control the problem by growing resistant species, pruning off branches infested with eggs before they hatch, removing the beetles or larvae by hand, or treating the plant with an organic insecticide that contains spinosad.

Which are the best viburnums for fragrance, berries, and fall color?

Vincent A. Simeone replies: Choosing favorites in these three categories is like asking who your favorite child is, but I’ll try. You’ll find the best fragrance from Koreanspice viburnum; there are several different cultivars and hybrids, all of which offer pure white flowers tinged with pink and a distinct, spicy fragrance in midspring. Many viburnums offer an attractive fruit display, but my favorite for exceptional berries are linden viburnums (V. dilatatum and cvs., Zones 5–8)—specifically, Cardinal Candy™. When it comes to fall foliage, I would choose doublefile viburnums as the most colorful because they offer rich shades of crimson red, orange, and maroon in cool weather.

Half of my shrub looks dead after winter. How can I prevent this damage?

Jeff Gillman replies: It’s important to determine whether the shrub or parts of the shrub you’re concerned about are dead or just look dead. Take a sharp knife, and gently scratch away a small amount of bark from the limbs that seem damaged. If they appear green and moist below the bark, then chances are the branches are alive and will recover over the next year or two. If the branches are brown and dry underneath the bark, then prune those stems back to where they connect to a main branch. If there are only a few dead branches, then the shrub should recover quickly; if the entire shrub is damaged, then you may need to consider planting something new.

The best way to protect against this type of damage in the future is to make sure that the shrub is properly watered going into winter. You can also construct a windbreak out of burlap to block drying winds. Wrapping plants in burlap is not helpful nor are antidesiccant or antitranspirant sprays.

What is the best way to move an established plant?

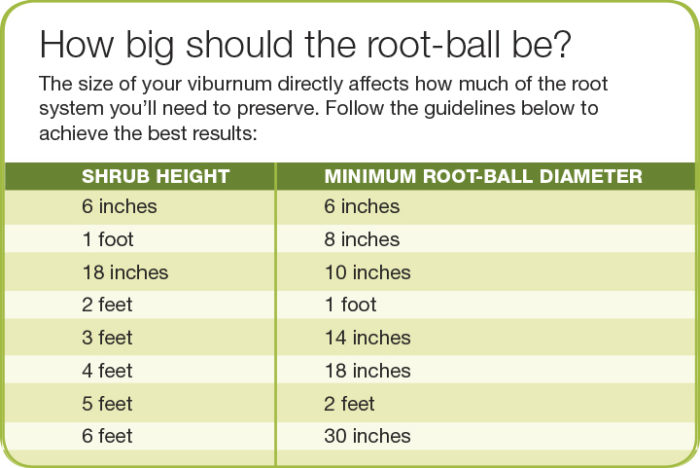

Andrew C. Bell replies: Viburnums, generally speaking, are not tricky to transplant. Just keep these three points in mind if at all possible: Avoid doing so during the growing season, dig an adequate root-ball for the size of the plant, and don’t forget that aftercare is essential to the plant’s survival. The best method for moving an established shrub is to ball-and-burlap it or to take the “naked-ball” approach. Most gardeners will chose the latter because it doesn’t make sense to burlap the root ball of a shrub that you are just moving to a different spot in the same garden. Follow the American Nursery and Landscape Association’s nursery-stock guidelines to determine what size root ball to dig (chart below). Once the intact root ball is cut free, carefully slide it into a wheelbarrow or onto a tarp, then gently pull or carry the plant to its new location. For small shrubs, I like to use an empty plastic container for transporting.

When replanting, the root ball should sit slightly higher than ground level because this will prevent water from collecting next to the base of the trunk, which will cause the shrub to rot. Remember to water thoroughly and to mulch. There is no need to prune the shrub to compensate for root loss (which is sometimes recommended); remove only broken or diseased branches. Early spring is generally best for transplanting because most people are in the gardening mind-set and more likely to keep up with essential watering. If a plant must be moved while actively growing, daily watering is essential and some dieback is likely to occur. Viburnums can be successfully transplanted in fall, however, and, in milder regions, through the winter months, as well.

Do they need to cross-pollinate to produce flowers and berries?

Gary Ladman replies: As a general rule of thumb, viburnums are not self-fertile. This means you need two compatible plants to cross-pollinate to get the best fruit production. Two viburnums are not required, however, to produce flowers. Flowering occurs whether or not pollination occurs. Pollination takes place thanks to certain insects (bees and flies) and wind. It can occur between different viburnum species, but unless you know which types are compatible with each other (because not all are), pick two plants within the same species to ensure proper pollination. It’s important, though, that the shrubs are two different viburnums. Blue Muffin® viburnum (V. dentatum ‘Christom’, Zones 3–8), for example, will not pollinate another Blue Muffin® because they are genetically identical and, therefore, incompatible; instead, plant a different cultivar of V. dentatum. Both plants must be blooming at the same time for pollination, and although there is no set rule on how close the plants should be to each other, the closer, the better.

How do I prune a viburnum?

Paul Cappiello replies: The short answer is: Put the pruners away, and pull up a hammock. Viburnums are wonderfully self-maintaining plants. You can prune out the “three D” offenders: dead, diseased, and damaged branches. But if you feel the need to snip beyond that, there are a few simple rules to keep in mind:

1. Crossing branches are a lost cause.

If you are planning to remove all crossing branches (as recommended by pruning books), get ready to quit your day job because you’ll be there forever due to the natural habit of a viburnum.

2. Wait for winter if you renew.

Overgrown plants will sometimes need a major renewal pruning (right). Be sure to wait for late winter and then cut back the entire shrub to about a foot tall. You’ll sacrifice the ensuing spring bloom season but will get maximum regrowth. And remember, renewal pruning works best on the heavily suckering types, like arrowwood viburnums (V. dentatum and cvs., Zones 3–8) and linden viburnums.

3. Bulk up a sparse shrub with spring snipping.

As with most plants, pruning is most effective when plants are young. If you buy a new plant that is a little on the sparse side, you can snip the new growth in half early in its growth cycle (midspring), and after a few seasons, you’ll have a more densely branched shrub. But really, don’t the hammock and a tall glass of iced tea sound like much better options?

Is there one suited to containers?

Stacie Crooks replies: I use three different viburnums in my containers.

The broadleaf David viburnum (V. davidii, Zones 7–9) stays less than 4 feet tall in a container and has glossy leaves, white winter flowers, and metallic blue berries in summer. For a shrub, it shares water well in a large container and tolerates a hard pruning to keep it inbounds.

To make a statement in a large container, I use leatherleaf viburnum (above). It can reach 12 feet tall and wide, but it is easy to keep pruned to fit your particular pot. Its white spring flowers are fragrant, and its leaves have a thick, leathery texture on the topside with a fuzzy underside.

A deciduous viburnum that works well in a container is the cultivar ‘Dawn’ (V. bodnantense ‘Dawn’, Zones 7–8), which blooms from late fall until spring with fragrant, deep pink clusters of flowers. The long, dark green leaves have deep burgundy veins. This viburnum is a real show-stopper in every season but especially in fall, with its deep scarlet color. This variety is also easy to keep pruned, or if you have a large container and enough space, you can let it become a small tree.

Are there any good options that are hardy in cool zones?

Ed Gregan replies: Many great viburnums are hardy to Zones 3 and 4; some are even hardy to Zone 2. Many of my favorites are native to the United States. Arrowwood viburnums have white flowers, exceptional berry displays, and structural leaves that get good fall color, and they are adaptable to many soil types. These plants spread by suckers and make excellent hedges. Another stellar option for cool spots is the American cranberry bush (V. trilobum, Zones 2–7). It is superhardy and has beautiful flowers, pretty fruit (above), and decent fall color. Nannyberry (V. lentago, Zones 2–8) is one last option that grows into an attractive small tree and has blackish blue fruit, which provide an excellent winter food source for birds.

Our cast of experts

|

|

|

| Daniel Gilrein Entomologist at the Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County, New York | Vincent A. Simeone Director of the Planting Fields Arboretum State Historic Park in Oyster Bay, New York | Jeff Gillman Associate professor in the Department of Horticultural Science at the University of Minnesota in St. Paul |

|

|

|

| Andrew C. Bell Curator of the woody-plants collection at the Chicago Botanic Garden in Glencoe, Illinois | Gary Ladman Owner of Classic Viburnums in Upland, Nebraska | Stacie Crooks Garden designer in Seattle |

|

|

|

| Paul Cappiello Director of the Yew Dell Botanical Gardens in Crestwood, Kentucky | Ed Gregan Nurseryman and woody-plant specialist for Carlton Plants in Dayton, Oregon | Todd Lasseigne Executive director of the Oklahoma Centennial Botanical Garden in Tulsa |

Why Won’t My Viburnum Flower?

Todd Lasseigne replies: Viburnums, like many other shrubs, come in diverse shapes, sizes, and requirements. Although many viburnums are free flowering, others can be more recalcitrant. The following factors can work to either promote or deter flowering.

Fertility

As with other plants that are sometimes reluctant to bloom, fertilizers can be both friend and foe. Remember that fertilizers with high levels of nitrogen often grow beautiful leaves but few flowers. Either avoid fertilizers altogether or use ones that are high in phosphorus and potassium (right).

Age

Young plants (especially those grown from seed) are less likely to flower than older plants. This is just basic biology.

Light

Many viburnums require moderate to high light levels to flower, especially in profusion. If your viburnum is growing in dense shade, it is probably not going to flower well—if at all.

Pruning

Aggressive or severe pruning often causes many shrubs to revert to a juvenile condition—one in which they do not flower. Light pruning and thinning is fine, but if you have to drastically chop back your plant, you shouldn’t expect to see flowers for the next year or two.

Plant photos, except where noted: Danielle Sherry

Expert photos: courtesy of the experts

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

Corona Tools 10-Inch RazorTOOTH Folding Saw

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Ho-Mi Digger - Korean Triangle Blade

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Chapin International 10509 Upside-Down Trigger Sprayer

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in