There’s a dogwood dying in my backyard next to the property line. My neighbor finds that nearly dead trees depress her, but for some inexplicable reason, until it’s completely gone, I’m reluctant to cut it down. Over a glass of wine one evening, a solution surfaced that would satisfy both of us. We’d let a wisteria climb it. By the time the vine winds its way to the top, the tree will have evolved into little more than an inanimate support.

Learn more: 7 Gorgeous Climbing Vines That Won’t Take Over

There are more than two dozen ways that vines climb, but most are basically variations on four themes: twiners, and vines that climb by tendrils, aerial rootlets, or some type of hook. The wisteria is easy to figure out. The candidate my neighbor and I selected is the Chinese variety, Wisteria sinensis, which means it’s going to send out long shoots that will wind counterclockwise around a support, eventually hardening into twisted, woody trunks several inches in diameter. Japanese wisteria, W. floribunda, winds clockwise.

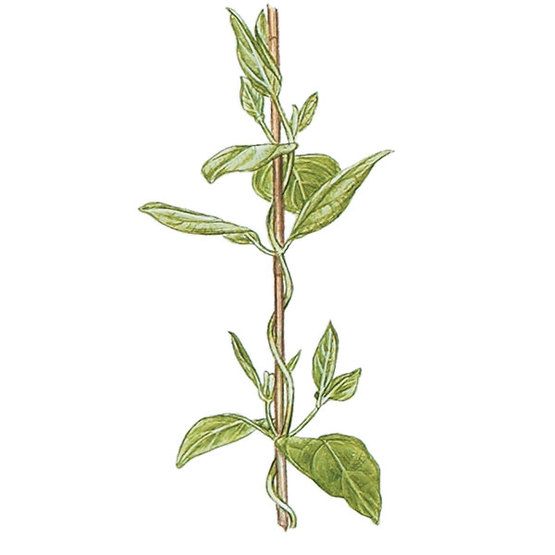

Twining vines such as these need only a sturdy support (for wisteria, very sturdy). Little coaxing is required. Hyacinth bean or lablab (Lablab purpureus), honeysuckles (Lonicera spp.), and chocolate vine (Akebia quinata) are all twiners. Each encircles its support in the direction predetermined by its genes. In some cases, a vine’s innate tendency is to climb haphazardly. But first, the tip of a twiner’s new shoot casts about in a wide arc until it finds an object to latch onto. Such efficient climbing allows you to spend energy elsewhere, since it’s often easy to tell whether or not the shoots are heading where they’re supposed to.

That’s not always the case with vines that climb by means of tendrils—angelhair-like antennae that whip about until they find a support, then wind around it. Depending on the plant’s heredity, the tendrils of these “clinging” vines can arise from either stems, leaves, or leafstalks. Members of the grape family (Vitis spp.), passionflowers (Passiflora spp.), and perennial sweet peas (Lathyrus latifolius) climb this way.

A little attention to the type and location of supports is important with tendril climbers, especially at first. Tendrils are short and profuse, erupting hither and yon. Thus, a few days’ absence from a pea patch, not enough supports at hand, and maybe a windy day to boot, may mean you meet an impenetrable mass of tangled foliage when you return. Tendrils that failed to find a support may simply latch onto a neighboring stem or each other. Instead of naively using string placed a couple of feet apart, as I did in my fledgling pea-growing days, I have since discovered the merits of chicken-wire fencing or mesh for controlling these vines.

Other plants—such as English ivy (Hedera helix) and wintercreeper euonymus (Euonymus fortunei)—climb by aerial rootlets and thus need no help, except in the beginning. They must only be reminded that they don’t have dominion over the earth. You’ll want to prevent them from smothering perennials, and if they’ve latched onto the side of a house, prune them away from windows and gutters and fish them out of cracks. Many of these true clingers hang on for dear life, so much so that removing the stems later leaves the roots—or their fibrous footprints—behind.

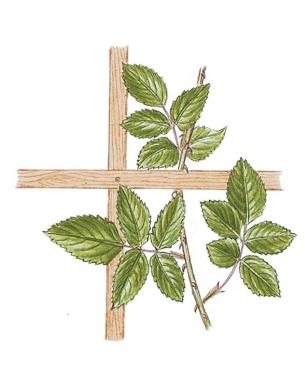

Some plants resemble mountain climbers, using hooks to grab toeholds on a support and climb skyward. The thorns of a climbing rose help gain purchase in a tree trunk or wood latticework, but the canes still need a little training. You’ll want to weave them through a trellis occasionally or tie them to a support.

There are a lot of variations on these themes. Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) forms tendrils, but they end in little sucker discs. The same goes for Boston ivy (P. tricuspidata), a close relative and not a true ivy. Clematis (Clematis spp.) can fashion tendrils or hook a leaf stem around a support.

What all vines have in common, though, is rampant growth and a limp nature. The profusion of foliage results from extensive root systems that provide a power-packed carbohydrate storehouse, very little of which goes into making cellulose for structural integrity—hence their need for support. While trees and shrubs expend energy building strong cell walls, vines use their energy to climb.

And there’s the caveat about growing vines: They may not want to stop. The vigor of a particular species may call for more than an occasional pruning. Thus, if you’ve cultured it well, ignored it a while, and the plant feels particularly frisky, you might have a jungle on your hands. A friend planted a passionflower against the porch trellis of her three-story home. She must have planted well, for every year she has to prune the vines away from the cable wires. Another friend who bought an old house for restoration first had to tackle a wisteria that had wreaked havoc on a wooden porch. At least the wisteria I planted is far from the house.

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

Attracting Beneficial Bugs to Your Garden, Revised and Updated Second Edition: A Natural Approach to Pest Control

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

The Regenerative Landscaper: Design and Build Landscapes That Repair the Environment

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

isYoung Birdlook® Smart Bird Feeder with Camera

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

I have a vine with a long stem and a white flower on it. Could you tell me what kind this may be?

Yes, we could.

Please, warn readers about the dangers (that go far beyond one's yard) of planting some of these vines! Nobody in North America should be willingly planting non-native invasive plants these days--we know better. The worst ones mentioned in this article are English ivy (Hedera helix) and wintercreeper (Euonymus fortunei), as well as Japanese or Chinese wisteria. These vines in particular escape captivity easily and are killing native trees and smothering native grasses and forbs.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in