Photo/Illustration: Steven Ash

Okay, Green Lacewing Larvae aren’t really vampires . . . they just feed like vampires, sucking out the body contents of their prey. Unlike the victims of vampires the prey of lacewings do not become the “undead” they, thankfully, become the “dead-dead”.

Life-Cycle: Green Lacewings, Chrysoperla carnea and C. rufilabris, are in the Order Neuroptera (neuro = nerve & -optera = winged). The complete life-cycle from, egg to adult, takes around four weeks. Like all arthropods (insects and spiders) development speed is very dependent on temperature, the warmer the temperatures (up to a point) the faster development occurs. Eggs are laid on slender stalks about ¼ to ½ inch long, this prevents them from being eaten by their siblings and other predators before they hatch. Eggs usually take a week or less to hatch, they start out green and darken just before hatching. Lacewing larvae go through three stages (instars), which takes about two to three weeks. They then spin a cocoon and the adult emerges in about 1-1/2 to 2 weeks.In colder climates, the cocoon is the usual over-wintering stage of this predator.

Dangerous (Beneficial) Stage: The Lacewing larva has mandibles that are similar to tusks. They grab the prey in their tusks, pierce its body and suck out the contents. It is amazing to watch a lacewing larva wade into a group of aphids, it’s like a National Geographic Special only you are actually there. Thus the larval stage of green lacewing is the dangerous stage, well dangerous to other insects. Actually they are even a danger to their own kind, since lacewing larvae turn cannibalistic when the soft-bodied insects and eggs on which they prey become scarce. Not a friendly family atmosphere. As a result of their voracious appetites, as larvae they can consume about 100 to 600 aphids, they are sometimes called Aphid Lions. This is a misnomer and doesn’t give proper recognition to the other prey of larval lacewings. Prey include: caterpillars, insect eggs (many kinds), leafhoppers, mealybugs, mites, psyllids, thrips, and whitefly, to name just a few primary pests. The larvae are “gutsy” too and are unafraid to attack insects larger than themselves, this is especially true with caterpillars. They also like a good long-tailed mealybug (Pseudococcus longispinus) meal and are an important predator of this difficult to control pest.

Bio-Control Tactics: There are four tactics for biological control: Conservation, Augmentation, Inoculation, and Importation (Classical). I won’t discuss the last one, Importation, which is bringing in and permanently establishing the appropriate natural enemies of a pest that has invaded a new area. Here are two examples of Importation: The Klamath weed beetle (Chrysolina quadrigemina) was selected and released for the control of St. John’s wort (the Klamath weed, Hypericum perforatum), which is toxic to cattle and sheep and had invaded vast swaths of pasture land. The beetle has all but eliminated this pest weed. The second is the Vedalia beetle (Rhodolia cardinalis) which was imported from Australia to combat the cottony-cushion scale (Icerya purchase) that was decimating the citrus industry in southern California. The Vedalia beetle is credited with saving the California citrus industry.

Conservation: This is protection of the biological controls already present in your garden and landscape. There are five tactics you can use to conserve beneficials:

1. Plants that attract and support beneficial insects. Seed mixes that support beneficials are available from a number of suppliers like Rincon-Vitova Insectaries, Home Depot, nurseries, and on-line suppliers of organic garden supplies. Most beneficials require certain plants to complete their life-cycles. Green Lacewing adults are Vegans! They eat only pollen and nectar. They don’t have long “mouths” like butterflies so they need shallow throated flowers such as alyssum, bachelor’s buttons, crimson clover, daisies, fennel, and other similar flowering plants. Letting carrots and parsley go to flower will also benefit Green Lacewing.

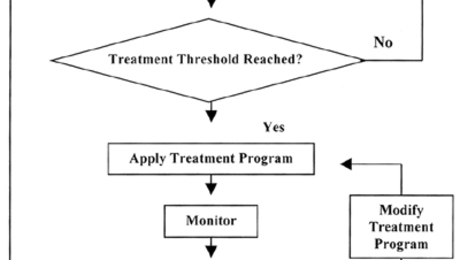

2. Treat only if injury levels will be exceeded. How much plant damage can you tolerate? Take non-toxic actions, such as washing aphids off of a plant, to reduce the pest population. Remember that predator populations always lag behind prey populations because predators increase in numbers as a “result” of feeding on prey, not in “anticipation” of it arriving. In fact it is usually just as the pest population reaches damaging levels that predator populations increase. Any pesticide use at this stage is likely to be a setback to the predators that have started to arrive.

3. Spot-treat to reduce the impact on the natural enemies of the pest. Restrict treatment to the very spot where the problem is serious and leave adjacent areas of the plant untreated. This is called, not surprisingly, a “Spot Treatment”. This ensures that some of the natural enemies will survive and can react quickly when the pest begins to multiply again. If you must treat with an insecticide, use the least toxic pesticide like Soap. Spot treat only where pests are in large numbers, DO NOT treat the entire plant as this will kill any beneficials present. If you do kill off the beneficials, you are likely to make the problem worse and may also end up with a secondary pest problem that was controlled by beneficials that were inadvertently killed by your pesticide application. Mites often become a pest when “insecticides” kill off their predators.

4. Time treatments so they are least disruptive. Timing should take into account both the season and the life cycle of the pest’s natural enemies. It should also take into account the life cycle of the pest, in other words is the pest vulnerable to this pesticide at this time. For example, scale are most vulnerable in the crawler (larval) stage when Soap insecticide can kill them. As eggs or when they are ensconced under their shells, they are immune to Soap insecticides. Timing varies by host plant, site, organisms involved and geographic area, this is where your record keeping comes in handy. Records help establish a “site memory” for your garden and give you information about what conditions are necessary for the pest to arrive and become established.

5. Select the most species-specific, least broadly damaging treatment. For example, Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) is toxic only to caterpillars, it doesn’t harm other insects.If you use a spot treatment, as precisely as possible, even a broad spectrum insecticide like Soap can be used without much damage to beneficials. Soap has the added benefit of breaking down quickly and becoming essentially inert once it dries. Soap sprays must actually come in contact with an insect in order to kill it.

Augmentation: This is simply releasing additional beneficials to help those that are already present in your garden. Since we know that predator populations lag behind pest levels we can bring more beneficials into the fray. This results in a quicker crash of the pest population. Augmentation is probably the most common tactic used in biological control. A subset of Augmentation is the “Inundative” release, which is when huge numbers of beneficials are released per unit area of garden. I have heard Inundative releases likened to a living pesticide application, sometimes the results can be seen the next day.

Inoculation: Releasing lacewing “before” the locals arrive is the heart of inoculation. Inoculation is carried out early in the season when pest populations are still low and beneficials are not yet present. It can also be done for late season infestations when weather has turned warm, the so-called Indian summer. Inoculation is distinguished from Augmentation because the beneficials are released before the pest population has built up rather than when pest populations are already large. Inoculating releases are done regularly, often because for some reason peculiar to the site, beneficials are unlikely to establish themselves permanently.

How Do I Do It? Conserving natural enemies should always be your first step and the elimination of broad spectrum insecticides is always the first step. I’ve found that the fewer insecticides I use the less I need. Be sure to include plants in your garden, especially around vegetables and fruit, that attract beneficials. These “insectary plants” are usually quite attractive and add to the aesthetics of your garden and landscape.

Buying beneficials (bennies) is the next step. Green Lacewing are available in all life cycle stages (except cocoons) from sources like Rincon-Vitova Insectaries. They also include detailed release instructions with every shipment. Overnight shipping is not only fast but it helps ensure the highest survival rate of your beneficials. Check shipments for viability before and during the release, reputable insectaries will replace bennies that die in transit.

Eggs are the most economical way to buy Green Lacewing. They are available loose and glued to cards that are hung on branchlets. I keep loose eggs inside until they begin to hatch, then I release them onto my target plants.

Larvae are available in hexcells, which are cardboard sheets that resemble honeycomb. Fine fabric is glued to both sides to keep the lacewing larva contained. One side is peeled back and the larvae are “tapped” out of the hexcel onto the plant. The larvae eat moth eggs that are added to the cells when they are initially prepared.

Adult lacewing are not predators! They are vegans, eating only pollen and nectar, hence the insectary plants you’ve planted. The adults are beautiful creatures. Light green bodies, nearly clear green tinted wings and golden eyes (see attached photo). We ordered some adults so we could take some pictures. One of the unexpected benefits was that during transit the females had laid eggs inside the container. We not only got adults for the neighborhood (adults usually “must” fly) we got a supply of eggs for the garden.

Try ’em you’ll like ’em: I recommend beneficials, whether through conservation or purchase. Remember, all the work that bennies do is work you don’t have to do. Don’t worry about “biological pollution”, green lacewing are native to North America . . . indeed to all temperate regions.

A few sources are referenced below. The first is the Natural Enemies Gallery website from the University of California Integrated Pest Management Program. The second is the webpage for Green Lacewing with four great pictures by the world renowned UC photographer Jack Kelly Clark. The third is a catalog of beneficial suppliers in North America, it is a little old but most sources are still in business. The last three are sources for beneficials that I’ve used myself.

http://www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/PMG/NE/index.html

http://www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/PMG/NE/green_lacewing.html

http://cdpr.ca.gov/docs/pestmgt/ipminov/bensup.pdf

http://www.biconet.com/biocontrol.html

Good Gardening! Steven Ash

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

A.M. Leonard Deluxe Soil Knife & Leather Sheath Combo

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in