For gardeners in the Midwest, interest in native plants is on the rise. Native plant enthusiasts recognize the crucial role these species occupy in relation to each other and to other animals that evolved in concert with them, all contributing to a greater diversity of flora and fauna. Research enlightens us as to the other services provided by these plants, including their impact on water quality and soil stabilization. For example, grasses native to our Midwestern prairies hold the soil much better and allow water and air to penetrate more deeply than do the grasses of a typical green lawn. Much of the region has experienced vast alterations to the natural landscape through urbanization, agriculture, and other human endeavors. This means there are fewer native plants to support native fauna, and these disturbances also make it easier for invasive species to gain a foothold.

It’s important to note that climate change and other factors are having an effect on the ranges of many plants, causing some to become more widespread while others are in retreat. Native ranges are slowly moving northward because of increasing temperatures, and that also means plants are becoming hardy in places they weren’t previously. On the flip side, some species are disappearing from places that have become too warm. Fortunately, we can still take cues from untouched landscapes that remain of Midwestern prairies, wetlands, and mixed forests to inform our garden choices. Here are some standout native plants that can add beauty and ecological benefits to your landscape.

Wild ginger

Wild ginger (Asarum canadense, Zones 3–7) forms a dense, 6-inch-high ground cover in mesic conditions and fully to partly shaded environments under deciduous trees and shrub canopies. It slowly colonizes an area via rhizomes and helps prevent the establishment of other species, including exotic invasives. Up to 6 inches wide and dark green, the heart-shaped leaves shine throughout the growing season, rarely bothered by insects or diseases, and also contain compounds that discourage mammalian browsing. The dark red, cup-shaped flowers often go unnoticed because they develop below the foliage, where they attract beetles, flies, and ants that assist in pollination and seed dispersal. Wild ginger is also an alternate host plant to pipevine swallowtail (Battus philenor) larvae.

Bottle gentian

Preferring moist, rich soil in full sun to partial shade, bottle gentian (Gentiana andrewsii, Zones 3–7) grows 1 to 2 feet tall with multiple, unbranched stems arising from a taproot. The floral clusters may display an ombre effect due to differences in age and exposure of the individual flowers, which do indeed resemble tiny (0.75 to 1.5 inch) bottles. Leaves are ovate, lance-shaped, and up to 4 inches long. They also take on purple tones in autumn. Except for occasional browsing by deer, the plant does not draw much interest from insects or animals who might chew on its leaves, nor is it a seed source for birds. Its greatest appeal is probably to humans, who appreciate this species mainly for the beautiful color and unusual form of its flowers. Bumblebees and some of the few pollinators with the size and strength to successfully access the nectaries without competition are able to pollinate the flowers.

Spicebush

First drawing attention in early spring, spicebush (Lindera benzoin, Zones 4–9) is a common denizen of native woodlands in the Midwest, where a colony of them evokes a chartreuse haze in understories when greenish-yellow flowers emerge well before foliage. It is best used in a naturalistic planting or hedge, and its habit will be more open the less sun it receives. It is usually a dioecious species, which means there are differences between the staminate (male) and pistillate (female) flowers. In this case the differences are subtle. The oblong ovate leaves are up to 5 inches long and take on a deep golden-yellow color in fall. Upon maturity in late summer to early autumn and shortly before the leaves drop, smallish, bright red fruits attract a variety of songbirds that consume them in short order. This usually multistemmed shrub may reach 10 feet in height and thrives in damp to wet, shady settings, but it can tolerate a drier or sunnier situation. Both stems and leaves are aromatic when crushed, hence the common name. It is an important food source for certain butterfly species, including the larvae of both the spicebush swallowtail (Papilio troilus) and Eastern tiger swallowtail (Papilio glaucus).

|

|

| These are two great books for information on gardening with native plants—one more general (left) and one specific to the Midwest (right). Photos: Jim Kincannon |

Resources for native plant information

A helpful source for determining whether and where a plant is native is the U.S. Department of Agriculture and its PLANTS database. By exploring their maps and other tools, it’s possible to determine if a species exists in a certain state (down to the county level in many cases) or Canadian province, and whether it’s native or introduced.

One of the most influential books of recent years is Bringing Nature Home: How You Can Sustain Wildlife With Native Plants by Douglas W. Tallamy. The author presents a compelling case for gardening with native plants by highlighting the interdependence of our indigenous flora and fauna. For a more regional book on natives, try Go Native! Gardening With Native Plants and Wildflowers in the Lower Midwest by Carolyn Harstad.

Land-grant universities and other educational institutions can provide a plethora of information, but also look into state and regional plant societies, parks, and nature preserves, as well as land trusts and other private entities focused on the preservation and promotion of native plants. Each state in the region also has an organization dedicated to native plants. Additionally, many of these groups sponsor periodic symposia, tours, and sales open to members and/or the public. Their websites are also great resources for finding other local plant sellers, seed exchanges, and nurseries. See the list below for some great regional sources of information.

On a personal level, be sure to follow this advice from the U.S. Forest Service:

Remember, respect and protect wildflowers and their habitats, leave only footprints, and take only memories and photos so that future generations may enjoy our precious natural heritage.

Regional resources

| Illinois | Indiana | Iowa |

| Michigan | Minnesota | Missouri |

| Ohio | Ontario | Wisconsin |

Jim Kincannon is a graduate of the School of Professional Horticulture at the New York Botanical Garden, where he also earned a certificate in landscape design. He is a Master Gardener and was a horticulturist at Newfields in Indianapolis, where he now volunteers.

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

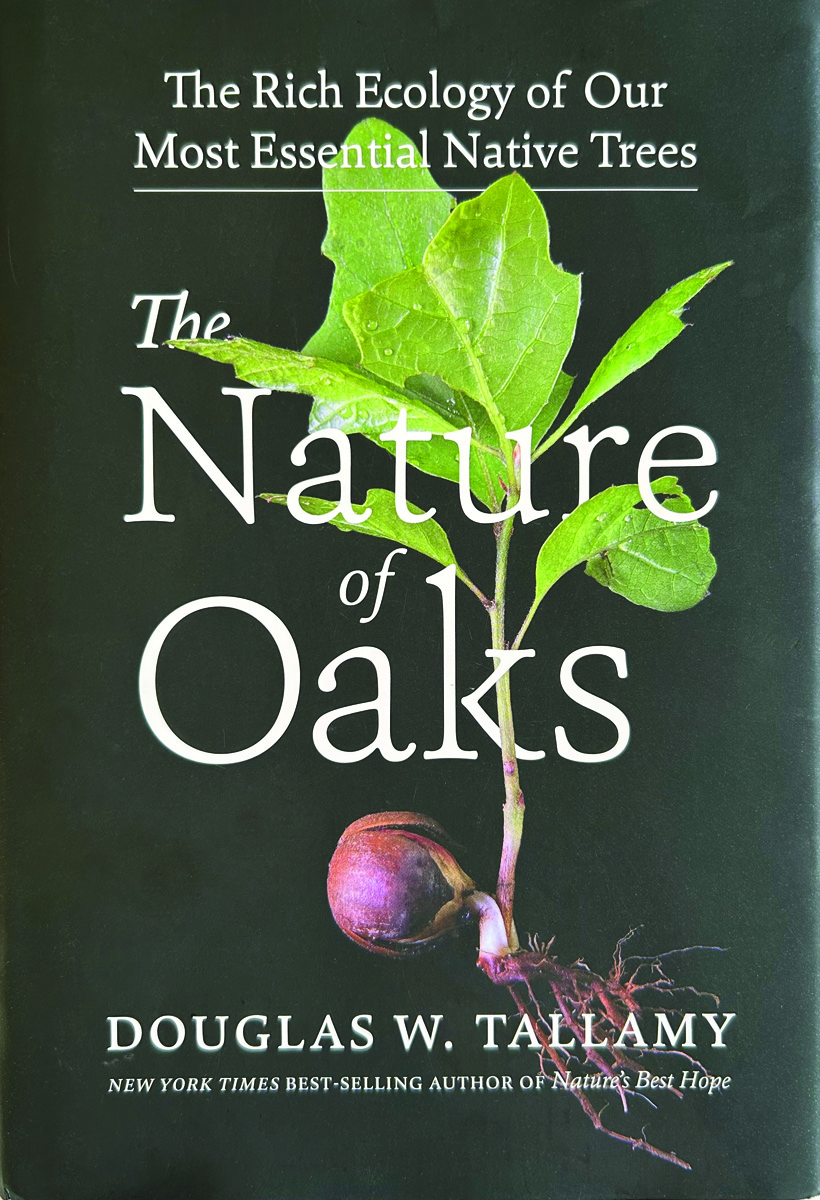

The Nature of Oaks: The Rich Ecology of Our Most Essential Native Trees

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

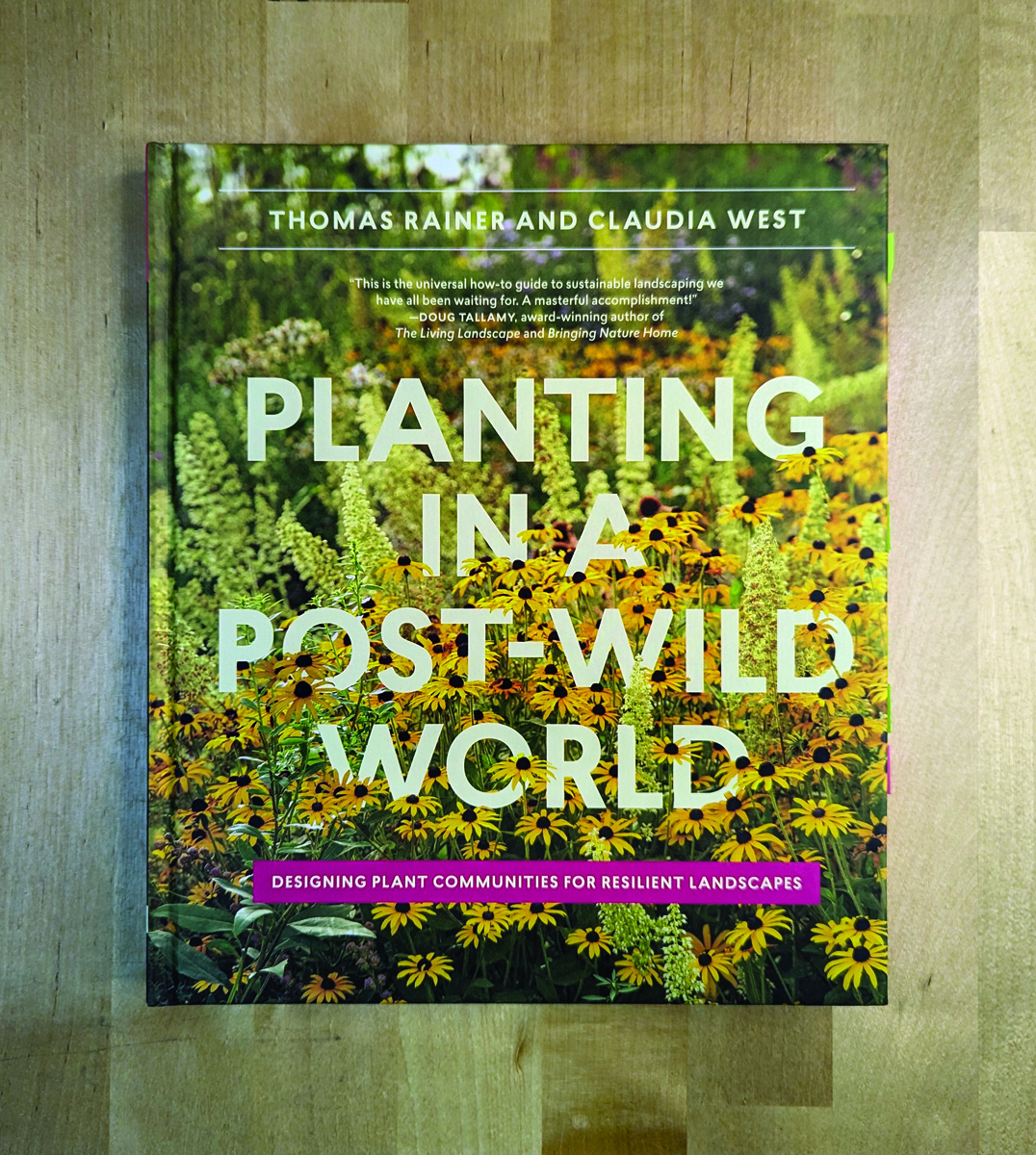

Planting in a Post-Wild World: Designing Plant Communities for Resilient Landscapes

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in