While I was in the Ozarks, I watched the persimmon trees (where there is an abundance of them in the wild) as the fruits turned orange and full fleshed, then some started to wrinkle and wither and began to fall and then the trees lost their leaves and the fruits hung on the bare branches. Some of the fruits were ready to eat a month ago–and some are still ripening–gather some now!

There are a few old wives’ tales regarding persimmons–and one of them is that there must be a frost before they are edible. I believed this to be true, until a few years ago, when I picked up a decidedly ripe persimmon from the ground and dared to eat it. It was sweet and delicious and not at all mouth-puckering. Eating an unripe persimmon makes your mouth feel as if it is full of alum and makes you pucker terribly from their astringency. An account from the logbook of Captain John Smith, written in the 17th century, when he and his men came upon the fruit reveals this characteristic: “if it be not ripe it will drawe a man’s mouth awrie with much torment.” Many a child has played a trick on another, unsuspecting child by getting them to try an unripe persimmon and watching them pucker up!

When perfectly ripe, the taste is manna–that of drippingly sweet fruit with a suggestion of maple syrup and deadripe apricots–the fruit virtually melts in your mouth and there is no astringency. The way to tell if the fruit is ripe, is that it should be orange in color and so soft that one has to be careful in handling it, lest the skin will break.

Often they fall to the ground when they are ready and that is the time to gather them before the other critters come to enjoy them. Sometimes folks, spread a sheet under a tree and shake the tree and pick up what falls. I pick up the fruit that isn’t damaged–and leave the ones that are bruised, dark, or have holes in them for the animals and birds. Donkeys love them, so I often toss them over the fenceline into the pasture.

Persimmons are about 34% fructose, so they are very sweet, and I like them best eaten out of hand. (They do contain a fair amount of potassium, and some iron, manganese, protein and calcium.) I do enjoy them in smoothies, though my favorite and most decadent way to use them is a simple and elegant mousse. I do this by combining equal amounts of pulp with freshly whipped cream that has been lightly sweetened with vanilla sugar, just fold the two together and serve right away or chill in some pretty glasseware until ready to serve.

The most common recipes you’ll find–they do make a lovely pudding and are tasty in baked goods from quickbreads and muffins to cookies and cakes. To preserve them, the pulp can be frozen or dried. The best way to remove the skins and seeds is to use a potato ricer, be it a conical one with a wooden pestle, or the hand-squeeze type, which looks like a giant garlic press. Though ricers work best, a food mill works okay as long as the holes are small. Freeze the pulp in 1-cup quantities or spread it out on baking sheets and dry it in the oven to make a fruit leather. Native Americans used to spread the pulp on logs with the bark removed to dry it.

Another popular folkloric use of the persimmon is to use the seeds to predict the weather. The seeds of the persimmon are very, very hard. And when taken out of a gooey persimmon, they are also very slippery. So washing them off may help. Regardless, great caution should be taken when trying to cut the seed in half. Inside, the kernel or the fibrous, white structure that is visible when you cut a seed open is really the root–and the shape of this root is what reveals the weather to expect for the winter. If it is too early in the season, the shape might not be as well defined.

The shapes can appear as a spoon, knife or fork. The spoon indicates heavy snow, which would need to be shoveled; the knife cuts as in icy, cutting winds; and the fork signifies a mild winter with light snow (which would pass through the tines) with sufficient food to eat.

Wild persimmons are found as far north as the Great Lakes and south to the Gulf, and from the Appalachians to the Ozarks. If you don’t have them growing in your area, there are cultivated Asian varieties of persimmons, which can be grown from zone 7 and warmer. California is growing most of the persimmons in our markets today. For more info on growing persimmons see the article written by Joe Quierolo: /item/4506/growing-persimmons.

The two main types of cultivated persimmons are Hachiya and Fuyu. The former is sort of acorn-like in shape and is more similar to the wild persimmon in that it must be soft and dead-ripe before eating or it will be astringent and unpleasant to eat. This will also be indicated because the fruit turns a bright orange-red color and becomes very soft. Fuyu, on the other hand is more yellow-orange in color and squat in shape. It can be eaten when it is orange and still firm and does not have the off-putting alum-like characteristics as the other persimmons do. Since it is firmer, it is a good ingredient in salads. The following salad sure sounds good to me: /item/4489/persimmon-and-fennel-salad

Now is the season for persimmons–gather them from the wild or look for them in your market–enjoy this sweet seasonal treat!

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

A.M. Leonard Deluxe Soil Knife & Leather Sheath Combo

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Berry & Bird Rabbiting Spade, Trenching Shovel

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

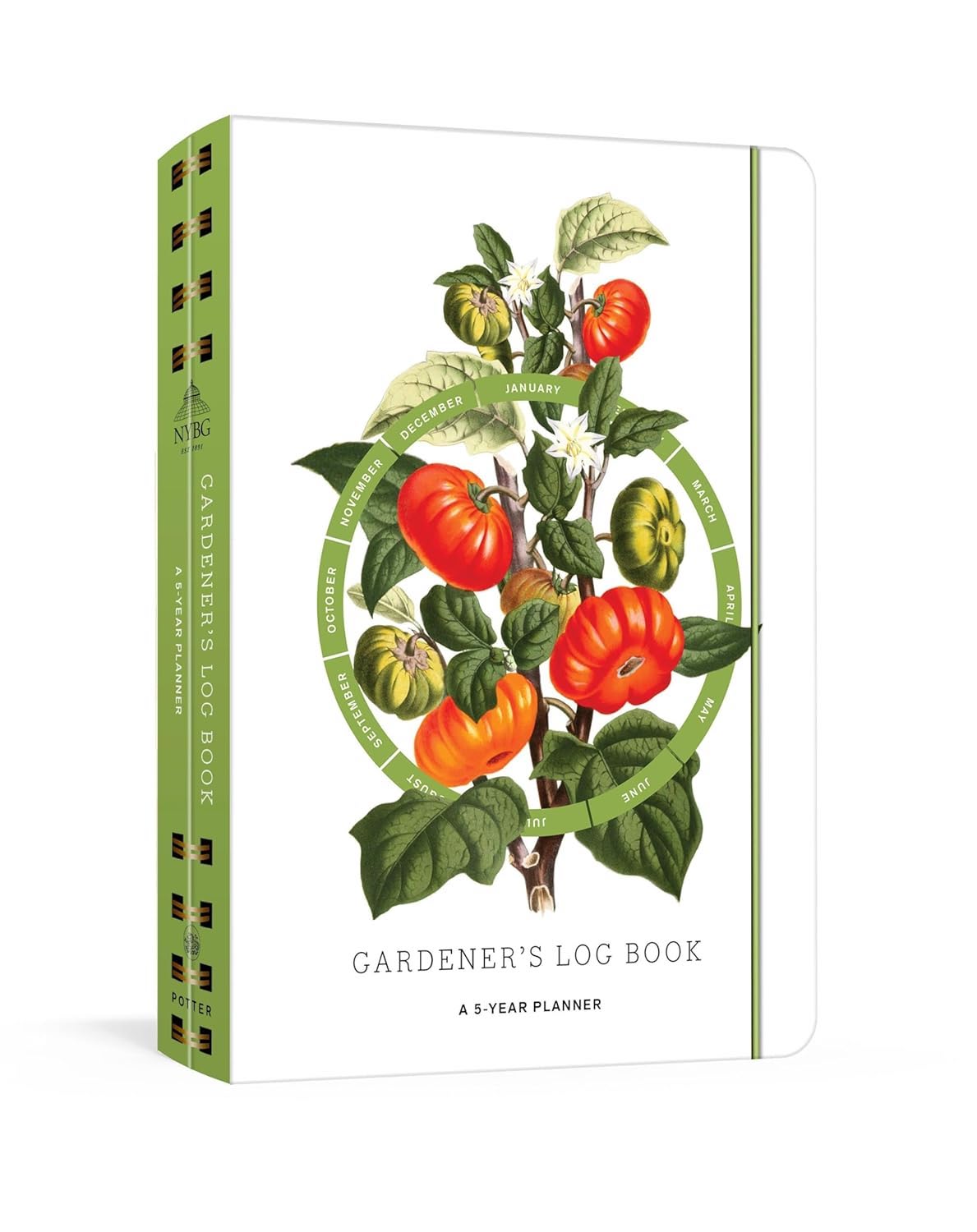

Gardener's Log Book from NYBG

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in