Harvest breads are a delicious, healthful, and natural link between the garden and the table. They can add color to your meals, seasonal harmony to a menu, and—much like a seed catalog arriving in the depths of winter—remind us of sunnier days and warm, sweet summer breezes. What more could you ask—except, perhaps, for a personal gardener?

In the days before all this personal business became fashionable—personal trainers, personal coaches, personal gurus, and the like—I was lucky enough to have a personal gardener. In truth, he wasn’t all mine. At the time, I was the chief cook and bottle washer for an adolescent group home here in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. And Michael was the staff property manager and gardener, a gardener so gifted I swear he could grow eggplant in Antarctica if he tried. Day after day, Michael would leave an overwhelming harvest in my kitchen—buckets of squashes, great bales of kale, towering piles of green beans, spuds, and corn. And day after day, I had to dream up clever new ways to use it all.

| Tips for making yeast breads

• When you make a dough, add the last 2 cups of flour about 1⁄4 cup at a time to make it easier to incorporate. • To start kneading sticky dough, use a dough scraper, sliding it under the dough and lifting it onto itself. • With most doughs, but especially these because they’re soft, don’t knead too vigorously, especially at first. Rock the dough rhythmically under your palms and don’t push down hard into the soft, sticky part of the dough. • When you knead, give the dough a 2- or 3-minute rest for every 2 or 3 minutes of kneading. The dough will become more resilient and easier to knead. • An unheated oven with the light on is a good place to let dough rise. • Before shaping a dough, allow it to relax, loosely covered with plastic, for 10 minutes. • To see if the yeast bread is fully baked, tap the bottom of the loaf with your finger. In most cases, a done loaf will give a hollow retort. |

Baking is my first love in the kitchen, so it was quite natural that much of what Michael deposited on my work table found its way into my breads, both quick and yeasted. I’m experimental to begin with, so dreaming up harvest breads became almost second nature. Cornbread on the menu tonight? Why don’t we replace some liquid with puréed squash? How would that pizza (or focaccia) dough bake up if we put in those leftover mashed potatoes? Would the muffins taste like carrot cake if we added grated carrots to them? (The kids would like that!) A harvest bread baker learns to think like this. He always has one eye trained on the garden, the other peeled for fresh new baking recipes to highlight the seasonal abundance.

The basic requirements for making harvest breads, then, are fondness for baking, access to fresh produce, and an inquisitive culinary nature. Beyond that, your everyday kitchen equipment will do: bread and pie pans, baking sheets, loaf pans, and an oven. And, of course, a platoon of willing eaters. But that’s the easy part. These harvest breads are so good, so attractive, and so good for you, that your main problem will be keeping up with the demand.

Which vegetables make the best breads?

If harvest breads are my passion, I’ve yet to sit down and codify the genre in any meaningful fashion. Still, there are some basic, prevailing themes that keep resurfacing over the years. The first includes those breads made with cooked vegetables, either mashed or puréed, and incorporated directly into the batter or dough. The most common vegetables used in this manner are sweet potatoes, winter squashes, and all-purpose potatoes. In the first two cases, you get the benefit of color; in all three, subtle flavor and a conditioning effect on the bread.

By conditioning effect I mean that these vegetables tend to soften the batter or dough, much the way it would if you used yogurt or sour cream for part of the liquid. You’ll notice this right away when you make the two yeast breads (the focaccia and the sweet potato bread). The doughs are somewhat softer, and stickier, than you’re probably used to. But that’s no cause for concern. When you knead them, simply use plenty of flour on your kneading surface and knead gently at first to avoid tearing the dough. You’ll also notice it with the cornbread, but in a different way: The conditioning effect weakens the structure of the bread, making it more compact. Compact but delicious.

| Four harvest-bread recipes… | |

|

|

| Carrot and Cranberry Muffins | |

| | |

|

|

| Golden Squash Cornbread | |

|

|

| Potato and Onion Focaccia | |

|

|

| Sweet Potato Sugar Bread | |

Sautéed vegetables, most notably onions, garlic, and mushrooms, have led to some very successful harvest bread experiments. I’ve made a sort of savory sticky bun or pinwheel roll using a large quantity of chopped, sautéed onions for the filling. The dough is rolled out, covered with the onions, then rolled up like a rug. This log is then cut into thick slices and placed, flat side down, in a buttered pan. Alternatively, a loaf’s worth of dough can be rolled into a 14-in. circle, covered with onions, then cut like a pizza into eight wedges. Starting at the wide end, roll up the wedges, pulling down the ends into a crescent shape. Let rise and bake. They make an excellent addition to your Thanksgiving bread basket.

This would be a good place to mention herbs, which I’d be more than likely to include in an onion bread such as the ones I just described. A few leaves of chopped sage or rosemary, which I’ve included in the Potato and Onion Focaccia, do much to underscore the harvest theme. Sometimes subtle is best. Just a whisper of a single herb added to a yeast dough can make your point better than a fistful.

Perhaps you’ve never thought of your favorite zucchini loaf as a harvest bread, but I do, and I include it under the grated- vegetable category. Zucchini adds moisture, but other than that, it is relatively transparent. Does anyone, I’ve always wondered, even taste the stuff? Grated carrots, on the other hand, add sweetness and a bit more texture than zucchini does. Here, I combine them with another seasonal standout, cranberries, for a colorful harvest muffin. Serve them at a special holiday breakfast. You won’t be sorry.

Harvest breads can make, or simply grace, the menu

This is the start of soup and stew season, both of which would find the perfect partnership with Golden Squash Cornbread. For a crisp, brown crust, bake it directly in a cast-iron skillet. The Potato and Onion Focaccia pairs off beautifully with soup as well, not to mention nearly any saucy, tomato-based dish. But one of the reasons I bake it in the pie pans to begin with is that the sides contain the dough and push it up. This added height, along with the softness of the bread, makes it nearly unsurpassable for sandwiches. (Cut the bread into six or eight wedges, then slice the wedges in half.) Sometimes our lunch will consist of nothing more than the focaccia, hot from the oven, dipped in olive oil.

The Sweet Potato Sugar Bread makes 12 generous portions. It can be served alone, or packed in lunches, but I also like to feature this for a brunch crowd, with a fruit course and an assortment of hot drinks— coffee, teas, mulled cider, and hot chocolate for the kids. It also makes a good potluck dessert.

My advice about baking all of these recipes is this: Pull them out of the oven as close to mealtime as possible. Otherwise you run the very real risk that they’ll disappear before you have a chance to serve them.

| A brief history of yeast

Wild yeast spores are constantly afloat in the air around us, landing in moist, warm homes where they can multiply, eating sugar or starch, and converting it into alcohol and carbon dioxide. The results of this effervescent lifestyle—beer, wine, champagne, and raised breads—were discovered by accident more than 5,000 years ago. Most likely the yeast found naturally on grape skins and grains got the chance to grow when someone let his grape juice or gruel sit around a few days too long and was rewarded with wine or beer. Raised bread probably came about when one of these fermented concoctions spilled into flatbread dough, and, voilà, light and tasty bread appeared in ancient Egypt.

Fast forward a few thousand years to Cincinnati 1865 when Austro-Hungarian stillmaster Charles Fleischmann visited for his sister’s wedding and declared poor yeast the reason for low-quality American bread. At the time, northerners favored salt-rising bread, while southerners were devoted to baking-soda hot breads. Yeast for baking was skimmed from potato water or vats of ale. Fleischmann changed all that. He and his brother Maximilian emigrated to the United States and began producing compressed Fleischmann’s yeast, which they sold to housewives by horse and wagon. In 1870, they started wrapping it in tinfoil, allowing shipment anywhere. To give this new-fangled leavening agent a boost, Fleischmann brought an Austrian baker to the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition and set up a model Viennese bakery so fairgoers could see, smell, and taste the delicious possibilities of baking with yeast. The rest, as they say, is history. |

by Ken Haedrich

October 1997

from issue #11

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

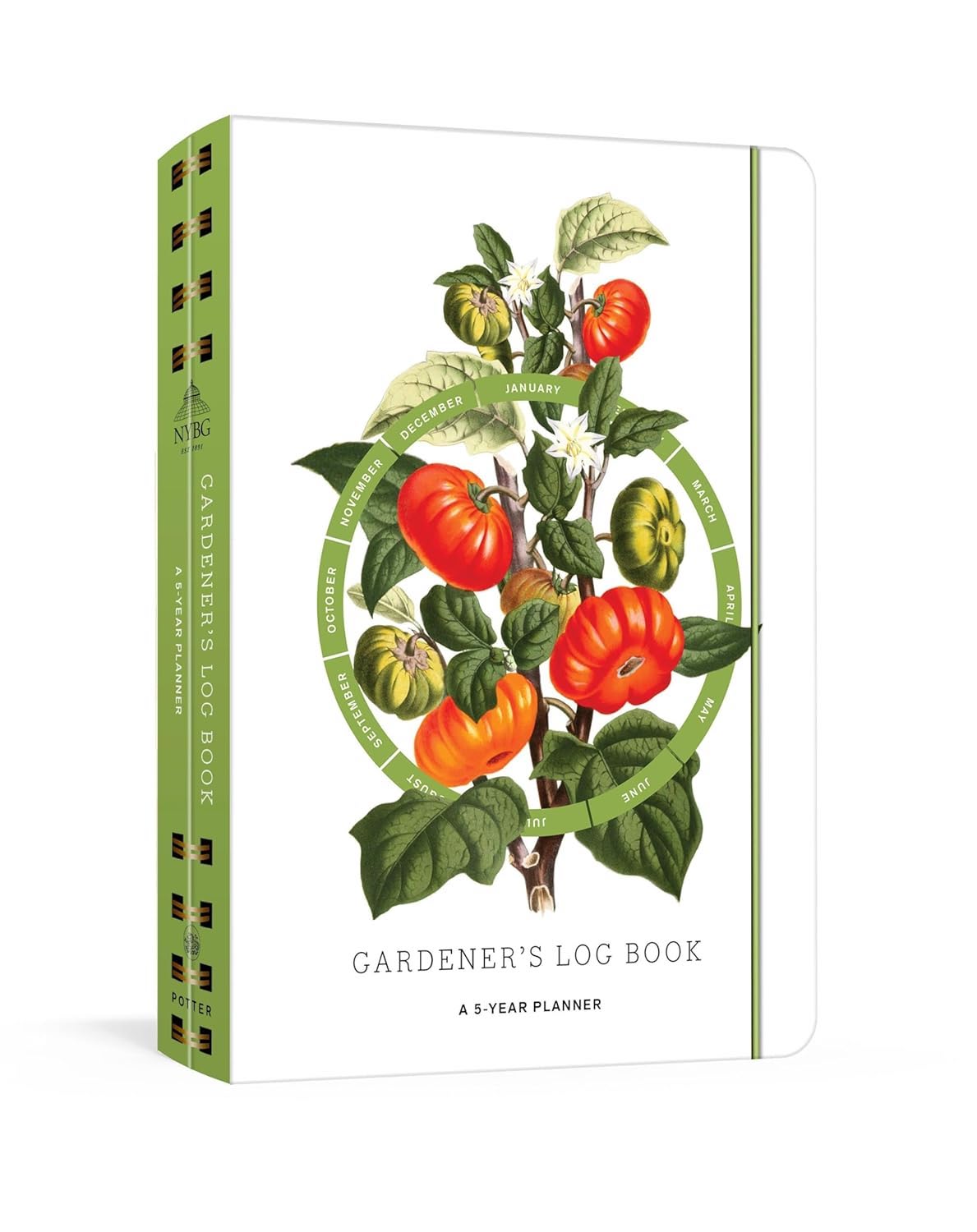

Gardener's Log Book from NYBG

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

A.M. Leonard Deluxe Soil Knife & Leather Sheath Combo

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Berry & Bird Rabbiting Spade, Trenching Shovel

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in