Until recently, most of us believed that garlic is garlic is garlic—and with good reason. For decades, most U.S.-grown garlic was raised in and around Gilroy in north central California. The garlic grown in America’s Garlic Capital is primarily one variety, ‘California Early’, a softneck garlic with large bulbs containing a dozen or more plump white cloves, some large, some inconveniently tiny. Its heat, which increases after storage, is moderately intense, and its flavor is pleasantly garlicky, if limited in subtlety and nuance.

As late as the 1970s, nearly all of Gilroy’s garlic was dried and processed for garlic powder and garlic salt, but as we have grown ever more enamored of the savory bulb, an increasing amount is sold fresh. Not so very long ago, the only fresh garlic you could find was in a small cardboard box and was often so old that it had turned to dust. Now, good fresh garlic is everywhere. Many home gardeners and small farmers are growing garlic, giving it to their friends, and selling it at their local farmers markets. Garlic fans around the world exchange cloves of unusual varieties by mail. For the garlic lover, life has never been better.

Tracing a culinary trend

The garlic revolution was launched in 1974 with the publication of The Book of Garlic by Lloyd J. Harris, who went on to found Lovers of the Stinking Rose, a garlic fan club. Harris either created or captured—it’s hard to know which—an exuberant, lusty silliness that defines the typical garlic lover.

The delightful 1978 film Garlic Is as Good as Ten Mothers, directed by Les Blank, celebrates both the Gilroy Garlic Festival and the Chez Panisse Garlic Festival. The same year, Chez Panisse chef and owner Alice Waters dazzled food critics when she served whole roasted garlic bulbs at New York’s Tavern on the Green. Cooking in America has never been the same.

A cook’s tour of the garlic patch

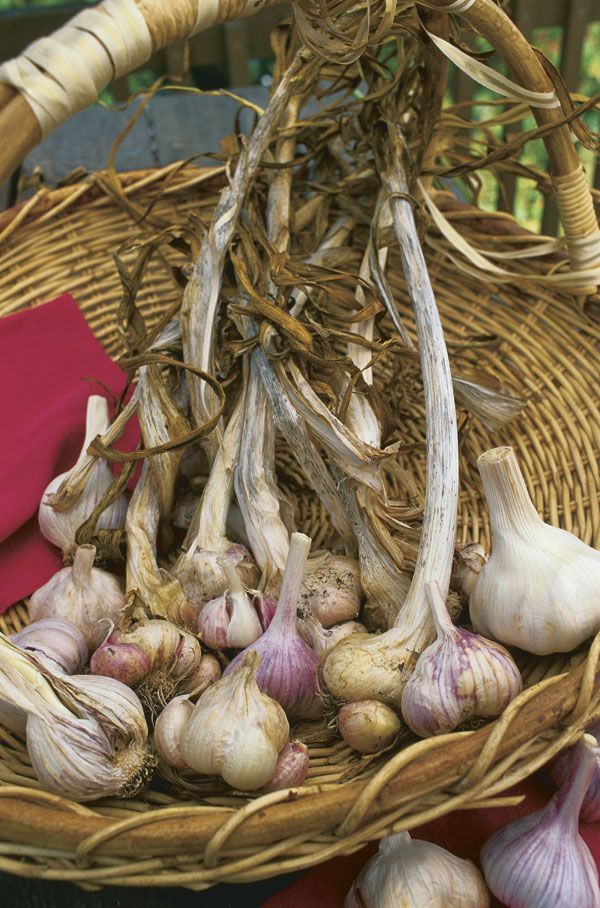

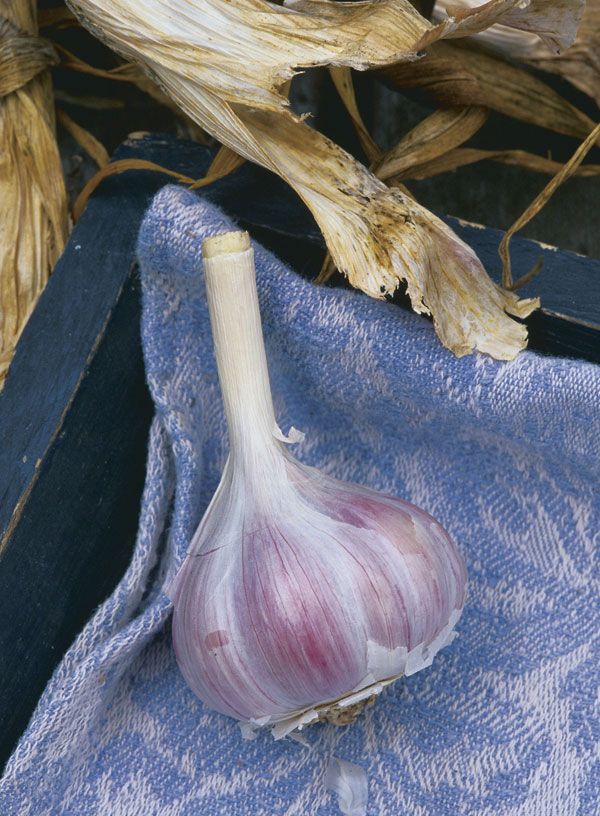

“It takes nine months to produce garlic, just like having a baby,” says Egmont Tripp of Sunshine Farms in Cloverdale, California. Tripp grows dozens of varieties of garlic using seed stock from as far away as Lithuania and Ukraine. He harvests his garlic in July and sells it in braids, in collections of several varieties, and in bulk. He also has a Garlic-A-Month Club. Some of Tripp’s seed garlic comes from Northern California grower Chester Aaron, who has written two books about garlic, Garlic Is Life: A Memoir with Recipes and The Great Garlic Book: A Guide with Recipes, both from Ten Speed Press. The Great Garlic Book includes photographs of more than 50 varieties of garlic. If you’re used to the white uniformity of ‘California Early’, you’ll be amazed by the diversity, beauty, and flavors of other varieties.

Plant garlic in the fall—during the October full moon is a good time for most areas. There are dozens of both hardneck (Allium sativum var. ophioscorodon) and softneck (A. sativum var. sativum) varieties. Most commercially grown garlic is softneck, which is easier to grow and holds up better during months of storage—an important consideration because garlic is all harvested in the summer.

Softneck garlic is used for garlic braids. Hardneck garlic, with its stiff stalks, cannot be braided, but many enthusiasts prefer the subtle flavors of these garlics. If you grow your own, plant both. If you don’t already have garlic in your garden, begin searching farmers markets in early July.

Garlic in the kitchen

There are two rules to remember. First, never store garlic in the refrigerator, where it quickly will dry out and rot. A cool, dark pantry is ideal. Ceramic garlic pots are attractive, but they rarely hold more than a couple of bulbs, less than a true aficionado’s daily requirement. I keep mine in a large terra-cotta flower pot.

Second, garlic burns very quickly if cooked over high heat, and once burned, it becomes bitter and must be tossed out. When frying whole, peeled, or minced cloves, use enough olive oil or butter to coat the pan; stir the garlic, and never take your eyes off it. Generally, you don’t want to cook garlic for more than a minute or two before adding other ingredients.

The biggest chore—especially if you’re using lots of garlic—is peeling it. There are some tricks to make this task go quicker. Peeling just a few cloves is a simple matter. I hold a single clove lengthwise between my thumb and forefinger and squeeze until the skin pops away. Then I pull off the skin and use a sharp paring knife to slice off the root tip. If the garlic is several months old, the skin may not pop off quite as easily as it does when the garlic is young and moist. With older garlic, I set a clove on a firm surface and press down, slowly and steadily, with the heel of my palm until I feel the skin loosen. (Be careful not to press so hard that you crush the garlic.) You can also use the broad side of a large knife in the same way, but you don’t want to smash the knife down on the garlic. Rather, set it carefully on top of the clove and use the heel of your palm to press steadily on the knife. Then use your fingers to pull off the skin.

To peel a lot of garlic, I use an E-Z Rol garlic peeler. I insert several cloves into the pliable rubber cylinder and then use my hands to roll it back and forth to loosen the skins. It’s fast and easy, and the device itself is inexpensive. If you want pressed garlic, you can put an unpeeled clove through a garlic press.

In general, hardneck garlics are easier to peel than softnecks, though many factors—especially age and clove size—influence the ease or difficulty in getting a clove out of its skin. All garlic is relatively easy to peel using the E-Z Rol. But I don’t let peelability influence the varieties I grow or buy. Taste, texture, and storability are paramount.

Keep in mind that the heat and characteristic intensity of garlic are contained within its cell walls. The more cell walls that are broken, and the more vigorous the breaking, the sharper the flavor as the active ingredient, allicin, interacts with oxygen. For example, a garlic press breaks down the cell walls more thoroughly and more aggressively than a sharp knife slicing through the garlic. For a wallop of heat in, say, a salsa, press a clove or two into the finished sauce. For more subtle flavor with less heat and more nuance, slice and then mince the garlic with a sharp knife. All garlic, regardless of how it has been cut, mellows as it cooks.

Many varieties have clusters of tiny cloves at the center of each bulb. They are, frankly, a pain to peel. I collect them in a container and toss them unpeeled into stocks or roast them with vegetables that will be puréed with a food mill.

In fact, when making stock or roasting garlic, don’t peel the cloves. Their flavor will season a stock just fine unpeeled, and roasted garlic to be served as a vegetable should be in its skin.

To roast garlic, place whole bulbs, their roots trimmed, in an ovenproof container, then pour in enough olive oil to come about a quarter of the way up the bulbs. Add about a cup of water, season with salt and pepper, add herbs if you like (fresh thyme, oregano, and marjoram are best), and roast in a 325°F oven for 45 to 60 minutes, or longer if the garlic is old. The garlic is done when a clove, pressed with your thumb, has the texture of room-temperature butter. Serve as an appetizer with croutons. You can also squeeze out the pulp, mash it to a smooth paste, and use it in soups, sauces, and purées of root vegetables. Because of its dense flesh, ‘Inchelium Red’ garlic is excellent for roasting; it also has a reputation for being difficult to peel, so roasting solves that problem.

When using raw garlic, the fresher the better. During summer, when fresh garlic is abundant, sample different varieties and choose your favorites. In The Great Garlic Book, Chester Aaron describes ‘Russian Red Toch’ as having the perfect garlic flavor, though he names others (‘Armenian’ and ‘Xian’ among them) as favorites. I love the fiery qualities of ‘Asian Tempest’, but I choose a more restrained variety, such as ‘Creole Red’, when a big kick of heat is inappropriate.

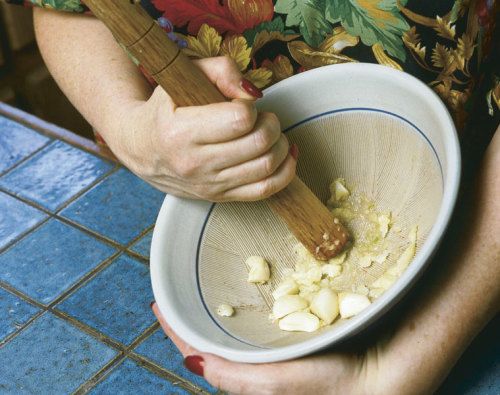

To grind garlic to a paste, the most effective tool is a suribachi, a Japanese mortar and pestle. The porcelain bowl of a suribachi is scored on the inside, a feature that is very effective in grinding. A mortar made of marble or granite works, but it takes longer. (You can find suribachis in most cookware stores; they are inexpensive, under $20 for the largest.) I always add a generous pinch of kosher salt when grinding garlic, which draws out moisture and speeds up the process. You can mince garlic in a food processor, but you cannot make a paste; processed garlic will never have the smooth texture of garlic pounded by hand.

As garlic ages, it loses moisture. Eventually, a shoot begins to grow from the center of the clove. The flesh of the garlic clove provides food for the shoot, which wants to be next year’s garlic. Both the flavor and the texture of the clove deteriorate as the shoot grows. If sprouted garlic is all you have until the next harvest, cut each clove in half and remove the entire shoot.

Seasoning or star?

Some recipes call for a single garlic clove, others for dozens. What’s the story?

Garlic has three main functions in cooking. First, small amounts are added to uncooked salsas and vinaigrettes, and to slow-cooked dishes like soups and stews. In such dishes, garlic is an aromatic, similar to onions, shallots, and leeks, all building blocks of flavor. It complements rather than dominates other ingredients.

Garlic also is a primary ingredient in many classic sauces, including aioli, the powerful Provençal mayonnaise; pesto; bagna cauda; and Thai chili sauce, the searing dressing made of serranos, fish sauce, lime juice, sugar, and garlic. Garlic is often added in large quantities to Indian chutneys, and it can be sliced, simmered in wine, and used as a condiment with roasted seafood, meat, and poultry (see the recipe for garlic conserve). In these and similar sauces, garlic is assertive and powerful, a defining element of the dish.

Garlic also is used as a vegetable. It is peeled, poached whole, and tossed with other vegetables. Chicken can be roasted on a bed of 100 or more peeled cloves that simmer in the juices from the bird and are served alongside. Garlic also is roasted whole or separated into cloves, solo or with potatoes, zucchini, eggplant, or squash. Once roasted, it can be mashed with other vegetable purées.

In each of these uses—as an aromatic, a primary ingredient, and a vegetable—fresh garlic with plenty of moisture is best. It cooks more quickly and is at its peak of flavor.

Garlic features prominently in the following recipes. Don’t be put off by the large amount called for in the bagna cauda and the conserve. In these recipes, simmering the garlic tempers its power to a deep, mellow, pleasant flavor. The dish that uses the least garlic—Pasta with Pancetta, Garlic, and Walnuts—is actually the most potent because it calls for garlic both raw and only briefly sautéed.

This article originally appeared in Kitchen Gardener #19 (February 1999).

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

A.M. Leonard Deluxe Soil Knife & Leather Sheath Combo

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Gardener's Log Book from NYBG

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Berry & Bird Rabbiting Spade, Trenching Shovel

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in