by Helga Olkowski

October 1999

from issue #23

Moles are much maligned, delicate creatures that improve the soil, eat many pest insects, and get blamed for damage they do not cause. At one time, they were prized for their velvety fur, and a farmer angered by mole activity could count on being able to sell the pelt for a good price. Although moleskin is no longer in vogue, killing moles is still popular. A better strategy is to try to tolerate them. In the long run, they are beneficial to the garden.

Moles eat many pestiferous beetle larvae, or grubs, and other insects, though they may also eat earthworms and centipedes and occasionally a small amount of vegetable matter, especially if it has been softened by water. The Townsend mole, found in the Northwest, eats more vegetation than do the other common mole species (there are seven in the U.S.), but a mole will starve to death if offered only plant food.

Gardeners most often object to the sight of mole tunnels or mole hills, perhaps fearing permanent damage to plant roots. In fact, the only real damage caused by moles is indirect, a result of their shallow tunnels lifting the soil and allowing plant roots to dry out. The best immediate response is to press back the soil with your foot and to water the area thoroughly to keep the roots moist as they re-anchor themselves in the soil.

Mole runways may be used by rodents such as voles, white-footed mice, and common house mice, which eat seeds, bulbs, and roots, and do cause direct damage to the garden and home fruit orchard. But these vegetarians generally have small home ranges, and a mole rarely stays in the same area for any length of time. Once it has eaten the local soil insects, it moves on.

If placed on the soil surface, a mole can dig out of sight in 10 seconds and will tunnel at the rate of 1 foot in 3 minutes. It can run through established tunnels at about 80 feet per minute. A mole spends about half its life searching for food in its underground tunnels, any time of day or night; it consumes about 40 pounds of insects in a year.

The mole’s body shows many adaptations to a life lived in narrow tunnels underground: a streamlined skeleton 5 to 7 inches long, fur that can point forward as easily as aft, a narrow snout, no external ears, small eyes covered with skin, and outwardly pointing claws and feet.

Its stout front claws are the mole’s only means of digging through the soil. The mole uses them alternately to push the soil away from its face and along the sides of its body. A rodent’s feet, by contrast, can be used to dig like a dog. Since they can be placed flat against the ground when walking or running, the rodent is as agile above ground as below. Not so the mole, who shows off its unique adaptations best when “swimming” through soft, moist earth

Although rodent skulls are comparatively tough, the mole’s skull is delicate. The mole cannot use its head in digging, thus its preference for soft, loose, moist soil. In fact, its head is so fragile and sensitive to vibrations that a mole can easily be stunned or even killed by the slap of a shovel over a tunnel where it is active.

Although its eyes are almost useless, probably helping the mole to distinguish little more than light from dark, its hidden ears are remarkable in their acuity, making it possible for the mole to locate its prey through many inches of earth. Its sense of smell is also excellent.

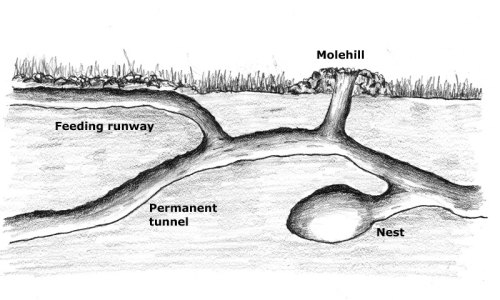

Two kinds of tunnels

A mole builds two types of tunnels. Its permanent tunnels may be quite deep and undetectable from the surface. Its nest, located in these permanent tunnels, may be 1 to 2 feet deep. Within these tunnels, the mole will be active year-round. It is its shallow feeding runways, sometimes used only once, that are of concern to gardeners.

If you are faced with an elaborate series of tunnels, it probably does not mean you have more than one mole, just a very active runway builder. Most species of moles are not gregarious. In fact, they are highly territorial and will fight to the death other moles attempting to enter their own burrow system.

| Anatomy of a mole tunnel |

|

| You’ll rarely detect a mole’s permanent tunnels, built a foot or more underground and leading to a nest that can be 2 feet deep. The familiar molehills are feeding runways, excavated close to the surface. What appears to be the work of many moles is more likely the industrious efforts of just one. A runway may be used only once, and a hungry mole can build an extravagant number of them in search of grubs and other insects. |

Mounds created by moles can be distinguished from those of the gopher by their shape, and by the texture of the soil used to build them. Mole hills are built like a volcano; the earth clumps thrown out through the center roll down on all sides. Gopher mounds may contain coarse dirt and form a half circle. The exit hole is on one side, and the earth is pushed away from it in a three-quarter moon shape.

Don’t rely on folk remedies

Various folk remedies have been repeatedly recommended for removing moles from the garden. If they appear to work, it is largely by coincidence, since moles don’t stay long in an area, or because of indirect effects that could also have been achieved by methods less picturesque.

For example, castor bean plants have been touted for mole control, the recommendation being to grow the plants around the garden and to place the seeds (which are poisonous to people) in the runways. Moles, however, will not eat castor beans. If the plants seem an effective barrier it is probably because they are fast-growing and quickly develop a large root system, which requires a great amount of water. By drying out the soil, they make it inhospitable to the insects and earthworms that might attract moles.

Create a mole barrier

Borders of stone-filled and/or compacted soil will discourage moles, because they cannot dig in such soil. The barrier must extend at least 2 feet into the ground. If the stony or compacted barrier is paved over, you can simultaneously create a mow-strip, walkway, and mole deterrent.

Another approach is to install a fence of 1⁄4-inch hardware cloth extending 18 inches under and 10 inches above ground. At its base underground, if the wire is bent in an L-shape pointing away from the area to be protected, it will also exclude gophers and rats. Extended 24 inches above ground, it will keep out rabbits, too.

Established fruit trees will benefit from the soil aeration accomplished by moles, but very young, newly planted fruit trees can be disturbed by the burrowing. Protect new trees by circling the root ball with a 1⁄2-inch hardware cloth cage. Overlap the ends of the wire mesh a couple of inches so the cage is temporarily closed to rodents, but leave the ends unsecured so the roots can gradually force the cage apart as the tree grows. Extend the wire mesh a foot above ground, creasing and pressing it closely around the trunk of the tree, to protect against mice as well. By the time the cage is no longer necessary underground, it will have rusted away.

Capture moles for relocation

Lethal, scissor-jawed mole traps do their job well and are easy enough to set, but we think a mole you insist on removing should be captured live and relocated.

Spring flooding, where it occurs in low-lying areas or streamsides, is a natural control of mole populations. The adults may manage to climb out of their tunnels to an elevated ridge or mass of drifting materials while they wait for the water to subside, but the young are extremely vulnerable in their nests, and even heavy rains have been known to drown them. Water can be similarly used to help relocate a mole you’ve deemed errant. It is likely to be most effective if used against West Coast moles that betray their deeper nests by throwing up large mole hills. Open the mole hill, poke a hose into the tunnel, and turn on the water. You can expect it to take a little while before there is enough water in the tunnels to flush the mole. Watch for the mole’s emergence from one of its other exits. Scoop it up with a shovel and relocate it outside the garden.

Moles can also be captured live in a pit trap, then released away from the garden. Determine which is an active runway by pressing down the tunnels and looking for one that is reopened. Open that tunnel and bury a large-mouth jar or coffee can in the path of the mole and cave in the runway just in front of the jar on both sides. Then cover the top of the disturbed section of the tunnel securely with a board. No light should penetrate the tunnel where the trap has been placed. A mole will not be able to climb out of a 3-pound coffee can.

If you have not caught the mole after two days, it probably means the mole is no longer working over that area or that you disturbed the area too much in setting the pit trap. Move the coffee can to a new location. Better yet, recycle the can and give the poor mole a break.

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

SHOWA Atlas 370B Nitrile Palm Coating Gloves, Black, Medium (Pack of 12 Pairs)

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Attracting Beneficial Bugs to Your Garden, Revised and Updated Second Edition: A Natural Approach to Pest Control

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

A.M. Leonard Deluxe Soil Knife & Leather Sheath Combo

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in