Bumblebees know a good thing when they see it. So do gardeners. And both buzz with approval when the wild indigo (Baptisia spp.) blooms. These rugged plants and their lupine-like spires of bloom are real attention getters. In early spring, when the white wild indigos wave their banners of bloom atop 3-foot spikes, there’s a refrain I hear over and over from visitors to the garden: “Wow! What’s that?”

Those impressive spikes of spring-blooming, eye-catching flowers— which, depending on the species are white, blue, yellow, or purple—are the main reason most gardeners grow wild indigos, but flowers are only part of their appeal. These are tough, virtually pest- and disease-free perennials with handsome foliage, intriguing seedpods, and a long season of interest. They’re all you could hope for from any perennial.

Nearly a quarter century of growing the genus Baptisia has only increased my interest in this wonderful, mostly southern group of native North American perennials. As curator of the North Carolina Botanical Garden, I have focused on propagating, growing, and telling gardeners about these worthy wildflowers. I have even had the privilege of introducing a superior form, Baptisia X ‘Purple Smoke’, to the nursery trade.

Wild indigos are worthy substitutes for lupines, which don’t like the hot, muggy southeastern summers. These sturdy American natives are so rugged, low-maintenance, and long-lived—not to mention beautiful—that it makes me want to salute them.

When mature, these perennials look like small shrubs

Photo/Illustration: Rob Gardner

Longtime favorites of wildflower gardeners, wild indigos have recently gotten a lot more attention from perennial gardeners. The flowers are one reason, but once the blooms are past, wild indigos undergo a transformation. When the spikes that held the flowers fill out with sturdy, attractive foliage, most wild indigos look like appealing, rounded shrubs. For a neater, more manicured look, you can clean up the plant—after it flowers— with a little pruning to get a flush of new growth. Some folks take this too far—I’ve seen them clipped into little, green meatballs.

Wild indigos do get large. A mature specimen might be 3 or 4 feet tall and wide, so they shouldn’t be planted in drifts. To me, they have the most impact when peppered singly through a perennial border, like repeating specimens. Wild indigos also look good in the middle of a perennial border; they can easily be used to anchor a whole planting.

Wild Indigo at a glance

Baptisia spp.

Bap-TEZ-e-ya

- A small genus of less than 10 species grown primarily for their dramatic spring flowers, wild indigos are herbaceous perennials native to the central and southeastern United States. Mature plants are large and stately enough to use as small shrubs in mixed borders.

- Wild indigos are tolerant of most garden soils, but need at least six hours of sun a day to thrive.

- Plant during fall in the South, or during spring in cooler climates. Wild indigos should get at least 1 inch of water a week in their first season.

- Cold hardiness varies by species, but all will grow in USDA. Hardiness Zones 5 to 8.

- Slow to establish, but ultimately drought-tolerant and long-lived. Wild indigos should not be divided, moved, or even disturbed. Propagate by seed or stem cuttings

- Very few pests or diseases prey on wild indigos, though voles may feed on their roots.

Wild indigos develop slowly, but they’re worth the wait

Easy to grow and long-lived, wild indigos impose very few demands on gardeners. In the wild, they grow everywhere from open woods and cedar glades to roadsides and old fields. So as you might guess, they find almost any average garden soil agreeable, and tolerate almost any pH. What they do demand is sun. They should get at least six hours of full sun a day, and the more the better. Once established, they are very drought-tolerant.

Here in north-central North Carolina (USDA Hardiness Zone 7), it is best to plant wild indigos in October or November when the roots will still have an opportunity to get a grip in the native soil before winter sets in. In fact, fall is the best time to plant any perennial in this part of the country. In colder climates, where frost may heave plants out of the ground, planting in the spring once the ground can be worked is best. However, if you are willing to check on them regularly and make sure that they get at least an inch of water a week during their first season, wild indigos can be planted at any time during the growing season.

Wild indigos are usually sleepers the first year or two in the garden. Their sparse foliage growth belies the fact that they are busy underground, concentrating their energy on the development of extensive, fleshy root systems that enable these tough plants to thrive for years even in poor, dry soils.

Even though mature wild indigos assume an attractive, shrub-like appearance, they are herbaceous perennials and die back to the ground with fall’s first killing frost. But as long as they get plenty of summer sun, they come back bigger and better each spring.

Be careful around tender new shoots, or you’ll forfeit the flowers

Many species of wild indigo emerge in spring with their flower buds foremost, usually at the tips of succulent stems which look like fat, young asparagus shoots. One misplaced step can easily crush or snap these brittle, embryonic shoots and destroy an entire year’s worth of wild indigo flowers. I carefully mark the exact location of all wild indigo plants in my garden in order to avoid this calamity.

To add interest to a perennial bed in winter, many gardeners leave standing any perennials that aren’t too untidy. Since the foliage of many wild indigos turns an interesting dark brown or black in the winter and the plants retain their decorative seedpods, they certainly qualify as having winter interest. Even so, I remove as much dead foliage as possible, and I just leave a few inches of stem behind when I cut wild indigos back. This helps identify their location during the off-season and prevents me from planting something on top of them. After all, I’m always looking for an empty spot in the garden!

Top-dress with compost in winter for best results

Tidying up the perennial bed also allows me to apply a layer of compost during the winter months. If there is one secret to good gardening, it’s soil improvement. Everything seems to benefit from a 2- or 3-inch layer of compost. I usually just top-dress with compost and let the worms and other soil organisms do the rest of the job. Wild indigos grow more vigorously and produce more flowers when given a top dressing of compost. Alternatively, you might give them a tablespoon or two of a balanced fertilizer, such as 10-10-10, in early spring, or feed them with a little Osmocote or other time-release fertilizer at the recommended rate.

Once established, wild indigos do not like to be moved, divided, or for that matter, disturbed at all, as digging tends to damage their succulent roots. The reward for allowing them to keep their own space is beautiful, trouble-free plants that will live for years.

Give seeds a hot soak

Wild indigos are very difficult to divide. They can be grown from cuttings, but are most easily grown from seed— though you’ll have to wait about three years before you get a flowering plant.

Their seeds have a very hard outer coat, and here at the North Carolina Botanical Garden, we’ve developed a technique for promoting germination. We pour hot, almost boiling water over the seed and soak it for six to eight hours to soften the seed coat. We then sow the seed in standard seed-starting mix.

Germination usually occurs in 20 to 30 days. Once the seedlings have produced two or three pairs of true leaves, we transplant them into their own pots, and fertilize them once a week with water-soluble Peters or Miracle-Gro at half the recommended strength. Then, we grow them on another two to three months until they are big enough to fend for themselves in the garden.

Grow wild indigos for their flowers and foliage

Photo/Illustration: Lee Anne White

White wild indigo (Baptisia alba) sports dusty, charcoal stems

Grace and elegance typify this wonderful, white-flowering wild indigo, the first of the genus to bloom. The contrast between its lofty, charcoal-colored stems, which look as if they’ve been dusted with powder, and the pure-white, lupinelike flowers is one of this species’ most attractive and dramatic features. New shoots emerge from the ground in early spring, rapidly grow into spires 2-1/2- to 3-feet tall, then bloom (in about mid-April in my garden) on stems unfettered by foliage. A four- or five-year-old specimen can produce 20 or 30 individual racemes, each bearing dozens of flowers. As one of the tallest early-blooming perennials, a mature white wild indigo in full flower creates a dazzling effect. With cool temperatures, the blooms can last up to three weeks. Plants thrive in USDA Hardiness Zones 4 to 9.

I like to grow white wild indigo with columbine (Aquilegia canadensis) in our garden of native plants. In a more eclectic garden, it would look good with late-flowering tulips. White wild indigo’s shrubby appearance also makes it at home in mixed borders.

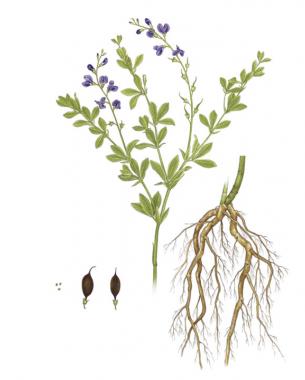

Blue wild indigo (Baptisia australis) will grow to 4 feet tall

Blue wild indigo’s beauty and durability have been long appreciated by perennial gardeners, so it’s no surprise that this is the most commonly offered and grown member of the Baptisia genus. Native to the eastern United States, it was introduced to England in 1758, and nearly 200 years later, in 1948, it won the Award of Merit from the Royal Horticultural Society.

Here in central North Carolina, blue wild indigo, also known as false indigo, begins blooming in mid- to late May—after its foliage has developed. Its beautiful racemes studded with violet-blue blooms rise above round, densely foliaged plants that can grow 4 feet tall. Blue wild indigo grows in Zones 3 to 9.

I particularly like the bluish cast of its trifoliate leaves. I love planting blue wild indigo with pink Appalachian smooth phlox (Phlox glaberrima ssp. triflora)—the combination is so vivid it seems to hum. Blue wild indigo is a beautiful partner for peonies (Paeonia spp.) of any color, which tend to bloom about the same time. This pairing makes for great color combinations and a wonderful contrast in texture of both flower and foliage.

Photo/Illustration: Rob Gardner

‘Purple Smoke’ wild indigo (Baptisia X ‘Purple Smoke’) has purple-eyed flowers

This wonderful hybrid Baptisia introduced by the North Carolina Botanical Garden has proven enormously popular. It is a cross between the two previously described species, B. alba and B. australis. Dusty-looking, charcoalcolored stems and smoky purple flowers are proof that ‘Purple Smoke’ combines the best attributes of both its parents.

The plant has been a standout from the time I first saw it as an openpollinated, chance seedling. After observing it for four years, I thought it was something special. I asked Kim Hawks, owner of Niche Gardens nursery, to give me her opinion one spring day when it was in full bloom. No less than 40 spires covered with purple-eyed, smoky-purple flowers were standing proud on a 3-foot mound of dense, gray-green foliage. Kim’s short but fervent endorsement: “Oh, wow!”

This plant looks great with almost anything that’s a soft yellow color. I particularly like it with Coreopsis verticillata ‘Moonbeam’ or ‘Zagreb’. ‘Purple Smoke’ thrives in Zones 3 to 9.

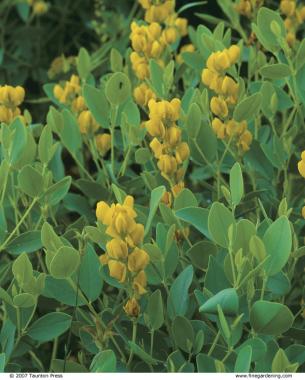

Yellow wild indigo (Baptisia sphaerocarpa ‘Screaming Yellow’)—enough said

I’d almost forgotten planting yellow wild indigo by the time it bloomed in my garden, so the drama of its acid-yellow blooms was a stunning surprise. The bold yellow blooms combine beautifully with the plant’s dense, yellow-green foliage. Pollinated flowers produce thick-walled, rounded seedpods that turn brown or black and become woody when dry. They are an identifying characteristic of the yellow wild indigo.

This attractive species from the south-central United States is as versatile as its relatives, but produces a much more compact plant and many more flowers if it gets plenty of sun. It rarely gets taller than 2 feet, with a somewhat wider spread. Yellow wild indigo is hardy in Zones 5 to 8. Although ‘Screaming Yellow’ is currently difficult to find, it should be widely available by next spring.

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

VegTrug Classic Cold Frame

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Berry & Bird Rabbiting Spade, Trenching Shovel

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

A.M. Leonard Deluxe Soil Knife & Leather Sheath Combo

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Help! My indigo baptista is just too big for its spot and didn't really bloom this year. I have to move it or lose it. Should I divide or just try to move? I'm in zone 5 so I'm thinking Sept?

Mine was app. 4' tall x 8' w, and covering adjacent plants.

As is the case with many suppliers of plants, their spec.'s on this plant are far, far off.

So sad, it was beautiful.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in