Mulch may make a garden look tidy, but the work it does to improve the growing conditions for plants is what makes it most appealing. Those layers of bark or pine straw also improve soil texture, suppress weeds, and conserve water. In nature, the forest floor is covered by leaves, twigs, fruits, branches, and decomposing plants for much, if not all, of the year. With the help of animals, microbes, and seasonal weather changes, these decomposing materials create a litter layer that protects the soil from erosion and weather extremes. We spread mulch in our gardens to mimic this natural process.

Not all soil covers make good mulches

Mulch is any organic substance used as a top cover to soil that enhances the rooting environment of plants. In this context, the term organic refers to substances that readily decompose. While they are often used as soil coverings, materials such as gravel, shell, volcanic rock, limestone, and granite screenings are not actually mulch. These ground coverings do not provide many of the benefits of mulch, such as holding moisture, moderating temperatures, and providing tilth for the soil. Since they retain cold or heat longer, they may keep soil too hot or too cold to benefit plants.

Organic mulches come in many forms, colors, and textures. Popular mulches vary by region and, for the most part, are related to what’s locally available. Most mulches sold commercially are by-products of forest harvesting. Much of the free mulch given out by cities and towns comes from utility-line clearing and tree trimming; some is made from recycled brush and Christmas trees.

The most common mulches are chipped or shredded bark, chipped tree limbs, or shredded whole trees that are too small for commercial harvest. Trees often used for mulches include southern pines, cypresses, northern hardwoods, and eucalyptus. Other common mulches include cocoa-bean hulls, pine straw, and leaf mold.

Recently, recycled wood pallets and woody construction debris have been ground up, dyed or stained, and marketed as mulch. I would be concerned, though, about the potential impact of dyes or stains leaching into the soil.

Many composted soil amendments, such as mushroom compost, manure, and grass clippings, are also used as mulch. While beneficial in nourishing soil, these materials decompose quickly. Thus, they are not as effective in moderating soil temperatures or retaining moisture unless they are reapplied frequently. Avoid using thick layers of grass clippings as mulch, since they can become a barrier, sealing the soil surface.

Choosing mulch involves both aesthetic and practical issues. Packaged materials are no better than bulk mulches from local sources, though they may be easier to move around. Mulches from local sources are sometimes thought to potentially transmit diseases and insects, but I’m not aware of any confirmed reports of plant diseases transmitted by mulch. Again, the best precaution is to use mulch that has begun to decompose. Both bagged mulches and those from municipal sources have usually begun to break down by the time they are available. As mulch ages, it becomes darker in color.

There are three common textures of mulch: shredded, tub-ground, and chipped. Shredded mulch is usually composed of thin strips of varying lengths of bark. Cypress and eucalyptus are the most common shredded mulches. Tub-ground mulch combines very fine to medium-sized particles. Because of the large amount of finely ground material, tub-ground hardwood mulch often has a dark, rich appearance. Chipped mulches are usually coarsetextured and commonly available, especially as free community mulch. While some mulch products specify the exact ingredients, others do not. I’m leery of bagged mulch that is labeled something vague such as “midwestern mulch,” since it may contain recycled construction materials.

As mulch decomposes, it releases either acidic or alkaline substances into the soil, depending on the mulch. This only matters if you’re trying to grow acid-loving plants like azaleas and rhododendrons. For these plants, use a mulch that releases acid, such as pine straw, pine bark (which is also high in aluminum), true cypress, and some species of eucalyptus. In contrast, hardwood mulches tend to become alkaline and are good for almost any plant that doesn’t require an acidic environment.

Mulch insulates and protects soil

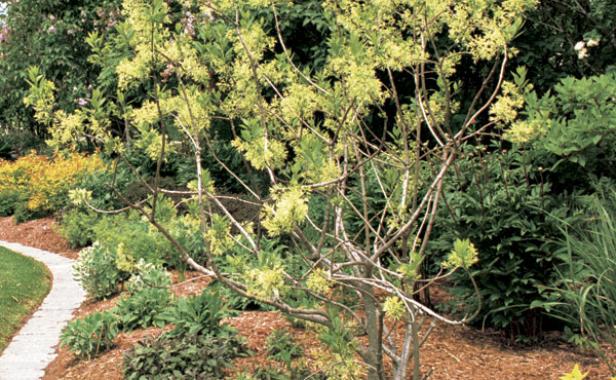

Mulching offers many advantages. First, mulches are attractive. They add texture to a landscape and enhance its appearance. This fact alone accounts for much of the widespread popularity of mulching during the past 20 years.

Yet there are even more significant long-term benefits. Properly applied mulch insulates soil and regulates its temperature. In summer, mulch absorbs the sun’s ultraviolet rays and transforms them into less-powerful, long-wave rays. Heat transfers to the soil through mulch more slowly than if the sun hit the soil directly. In the fall, mulched soil loses heat more slowly. A study I performed at the Morton Arboretum also showed that the minimum soil temperature in winter was as much as 10°F higher under mulch than under turfgrass. Warmer winter soil temperatures generally result in less root loss due to freezing. In summer, mulch reduced the maximum root-zone temperatures up to 12°F as compared with turfgrass.

The tempering of soil temperatures has one other benefit for areas subject to frost heave. Mulch decreases the freeze-and-thaw cycles at the soil’s surface in late winter, and plants suffer less root tearing from the heaving of soil.

Mulch also helps retain soil moisture by reducing evaporation and helping the soil to absorb rainfall. Mulch lessens runoff and potential erosion by eliminating direct contact between soil particles—which are easily dislodged—and raindrops, which can move soil.

While many gardeners use mulch for weed control, mulch simply shrinks the total weed population and makes it easier to pull out any remaining weeds. Most weeds root in the mulch, rather than the soil, and the loose nature of mulch makes weeding easier.

When mulch fails to serve as an effective weed barrier, many gardeners resort to landscape fabrics or sheets of plastic to provide a barrier underneath the mulch. In my experience, these materials often inhibit the flow of air and water, especially in silty or clayey soils. As much as I hate yanking out weeds, I still opt for handpulling the ones that rise up from a thick layer of mulch.

Be alert to infrequent problems caused by mulch

There can be a few minor drawbacks to using mulch, but only under very specific conditions. In the spring, wet soils will retain excess moisture longer under mulch than if the soil is bare and evaporation could occur. To avoid this problem, make sure your soil drains reasonably well before using mulch.

Another occasional problem is when a mulch produces a chemical that’s harmful or lethal to another plant. Called allelopathy, this can occur when a chemical-producing plant is used to mulch a sensitive plant. One of the most common allelopathic relationships is the antagonism between black walnut (Juglans nigra) and members of the nightshade family (Solonaceae). Black walnut produces a substance called juglone, which can harm or even kill plants such as species of Nicotiana, Datura, and Petunia. In regions where black walnut is common, it might be present in mixed-bark mulches. When obtaining mulch, try to find out what materials may be included in the mix.

The only other drawback involves the use of “green” mulch, such as fresh wood chips, which may produce a short-term reduction in available nitrogen. I have observed this only when hardwood materials went straight from the chipper to serving as mulch. As microbes in the soil decompose the green mulch, there are fewer bacteria that produce nitrogen and more fungal-decay organisms. During this brief transition—usually four to eight weeks—the foliage of plants that are sensitive to nitrogen-level shifts may become pale green or yellow. As the mulch breaks down, the microbial populations rebound and plants respond normally. If you use green mulch, add about one half pound of high-nitrogen fertilizer per 1,000 square feet of 4-inch-thick mulch to avert this problem. It can be added on top of or under the mulch.

Mulch generously, but not close to plant stems

The use of mulch is simple and straightforward. Apply mulch to the root zone of plants or throughout a planting bed. Use 3- to 5-inch layers that will settle to a depth of 2 to 4 inches.

Mulch should never be applied directly to the base of plants, including trees and shrubs. I often see mulch that has been mounded against trees until it looks like a volcano surrounding the trunk. This essentially buries part of the tree’s aboveground stem and increases the likelihood of basal rot and may even lead to the tree’s death. Instead, keep the entire tree stem exposed and layer about 3 inches of mulch out to the tree’s drip line.

Replenish mulch when there’s 1 inch or less of it. How often you need to replace it depends on how fast the material decomposes, exposure to the sun, temperature, the amount of rainfall, and the length of your growing season. Generally, I top off my mulch once a year. To keep from disturbing the soil, simply add another layer to the existing mulch.

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

A.M. Leonard Deluxe Soil Knife & Leather Sheath Combo

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

ARS Telescoping Long Reach Pruner

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

I occasionally have problems with mulch forming a hard layer... what's wrong?

Nice article to read on. Please refer to my article at http://www.greengoldlandscapinginc.com/what-is-pine-bark-mulch-and-what-are-its-benefits/

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in