Grow Vegetables All Year-Long With Cold Frames

A simple frame with a glass top can give you a 12-month growing season, even in a cold climate

Like most vegetable gardeners, I’ve always been interested in extending the harvest beyond the confines of “the growing season.” Along with the prolonged enjoyment of puttering in the garden, I treasure the reward of continuing to eat fresh, home-grown food. The easiest and most economical way to do this is with a cold frame.

If, like me, you’re not ready for the gardening year to end with the season’s first hard frost, then maybe you’re ready for a cold frame, too. This simple bottomless box with a removable glass or plastic lid protects plants inside from excessively low temperatures, wind, snow, and rain. In doing so, it creates a microclimate that is a zone and a half warmer than your garden. My garden may be in Maine, but the plants in my cold frame think they’re in New Jersey. A cold frame in New Jersey provides Georgia weather. The result is a harvest of fresh vegetables all winter long.

I began a serious exploration of winter cold-frame gardening back in 1981 when I took the job of farm manager at a private school in Vermont. The program was supposed to supply the school with food while engaging students in a hands-on way. The problem was that there wasn’t much overlap between the gardening year and the school year. To involve students in fresh vegetable production, it would have to happen in winter. And if winter horticulture were to catch on with teenagers, it would need more charisma than a Brussels sprout. A large, heated greenhouse was out of the picture, and so I turned to cold frames.

It’s basically a bottomless box with a skylight

The beauty of a cold frame is that it’s simple. Mine would have been familiar to a gardener a hundred years ago. Each one is a bottomless box made of 2-in.-thick planks, 12 in. high at the back and 8 in. high at the front, and covered with glass frames, called lights.

The back of the frame is cut higher than the front so the angled lights can catch the slanting winter sun. I site the frames with the lights sloping toward the south in a spot where they will have as much winter sun as possible. Some shade is tolerable, but full sun is best.

If you have access to old storm windows, you can use those as lights. If you don’t want to build your own frame, however, you can buy a sturdy, ready-made, polycarbonate-glazed cold frame for a few hundred dollars. (Companies that sell cold frames or materials to make cold frames include Charley’s Greenhouse & Garden and Peaceful Valley Farm & Garden Supply).

Grow cold-tolerant crops year-round

One of the keys to success is to focus on vegetables that thrive in, or at least tolerate, the cold. No, a cold frame isn’t going to put vine-ripened tomatoes on your table in January. But it will easily provide you with the best carrots you’ve ever tasted, firm-fleshed leeks and scallions, succulent cooking greens, and a host of salad ingredients.

Most of the popular vegetables Americans grow are “chilling sensitive,” which is to say they don’t appreciate temperatures below 50°F. There are, however, many “chilling-resistant” crops; these vegetables survive winter’s freezes, providing they have some protection.

Spinach is one of the best such crops. It yields all winter in the cold frame. So does chard. Scallions are good, too—even better from the cold frame than from the outdoor garden. Carrots are outstanding. I make a big sowing on August 1 and enjoy delicious, tender baby carrots all winter. A thick layer of straw applied in late fall protects them from temperature swings. The cold turns some of the carrots’ starch to sugar; my kids liked them so much they used to call them “candy carrots.”

A cold frame is a bonanza for salad lovers. Lettuce is available until about mid-December, when it finally succumbs to repeated freeze-thaw cycles. That doesn’t bother me, though, because there’s a true winter salad green for cold-frame growing, and that’s mâche, also known as corn salad. This traditional midwinter European salad crop is far hardier than lettuce. I’ve found that mâche can be harvested while frozen and still look beautiful after it thaws. Scallions also can be harvested frozen. The others need to be picked unfrozen. But that is really no problem because the interior of the cold frame gets above freezing on most winter days, even when it’s cloudy.

After learning about mâche, I began looking to Europe for more winter salad ingredients. Frisée endive is quite hardy, as is radicchio. But my three favorites are cultivated weeds. One is claytonia, a California plant also known as “miner’s lettuce” because it was eaten in the Gold Rush days. The round, succulent leaves on thin stems have a fresh, sweet taste and are second in hardiness to mâche. The Europeans imported claytonia and domesticated it to what they called “winter purslane.”

Minutina, a relative of the plantain weed, is popular in Italy. Minutina has slender, lightly fringed leaves that have a salty taste and crunchy texture. And in the chicory family, I found ‘Biondissima Trieste’, a nonheading type that can be planted thickly to yield abundant quantities of delicious, tender, round to finely indented leaves. Arugula, dandelion, escarole, mizuna, parsley, sorrel, and mustard and turnip greens are also resistant to chilling.

How many varieties you’ll be able to grow in your cold frame depends on where you live and the severity of the weather. For gardeners in Zone 6 and south, a cold frame will guarantee bounteous harvests. In the frigid winters of Zone 3, there are only five crops—spinach, scallions, mâche, claytonia, and carrots—that you can dependably harvest all winter, and only mâche during the coldest periods. If you want to increase the number of things you can harvest, erect a plastic tunnel over the cold frame, which will make a quantum leap in protection and crop variety.

|

|

|

|

Be sure to manage the cold frame

On a sunny day, a cold frame can quickly become a hot frame. You don’t want to be saving your crops from winter, only to have them cook before you can harvest them. A cold frame can overheat, even on a cloudy day. Keep the temperature below 60°F during the day by opening the frames a little. I can vent mine manually because I work from my home. I recommend installing temperature-activated ventilating arms to look after this task for you. I like the Univent control from Charley’s Greenhouse & Garden because it’s the only one I know of with a quick-release feature that allows you to open the light all the way. It’s always better to err on the side of overventing. If you’re going to be gone all day, or if you’re unsure about the weather, vent.

A minimum/maximum thermometer inside the frame helps me keep track of temperatures. In times of extreme cold, an insulated, reflective cover over the frames at night is helpful as long as it’s opened during the day to let in the sun. My frames have dropped to 10°F inside with no problem.

I’ll leave a new snowfall on the frames for a few days as insulation if it’s bitter cold. Heavy wet snow, though (6 in. or more), could break glass panes. I’ve found I’m less liable to break them myself if I remove the snow with a broom instead of a shovel. Once, when I was away, my frames spent three weeks under snow, and the plants didn’t suffer.

Occasionally people tell me that by fall they want a break from gardening. But that’s the best part: You can have your break and eat it too. After early fall, very little gardening takes place, just some watering until November and then no more until spring. Venting can be handled automatically. I’ve found no weeds or pests in my cold frames. Harvesting is the main task, which is the aim of all this activity anyway.

And how good is the harvest? I can best describe it as a season of continuous delight for the table as well as for the soul. Even after all the years I’ve been growing in cold frames, I still marvel at the contrast of the weather outside and the bounty within. I still find myself coming into the kitchen with a basket of fresh greens for the evening salad and exclaiming, “You wouldn’t believe what’s available out there!”

“Yes, we would. We’ve heard it before,” say the eager eaters. “Please stop enthusing and make the vinaigrette.”

|

|

Why all this talk about winter crops when you’re still waiting for the first tomato?

Because you can’t wait until winter to plant the winter garden. The rate that plants grow diminishes with the shortening days of fall until they almost stop. By then, the plants need to have reached harvestable size. After that, they’ll hibernate successfully in the shelter of the cold frame. I start sowing seeds in my cold frame in mid-July, but that’s because I live in Maine. You’ll need to adjust your planting schedule for your local climate.

Download plans, a materials list, and instructions for building this cold frame.

A cold-frame timetable

Probably the most important point in using a cold frame is to start your plants early enough. I begin in mid-July, sowing seeds for slow-growing or heat-tolerant crops like scallions, chard, parsley, and for winter greens such as escarole, endive, dandelion, and radicchio. On August 1, I sow my entire winter carrot crop. By mid-August, I’m seeding mustard and turnip greens. And in September I sow all the salad greens that germinate in cooler soil—mâche, spinach, claytonia, arugula, and mizuna, as well as radishes.

From time to time, spaces open up where a crop finally gives in to winter, or where I’ve harvested whole plants such as mâche. I sow seeds for new crops in these holes. Arugula, mâche, spinach, claytonia, radishes, and lettuce will germinate during the winter. If they fail, I try again. As the sun climbs higher in late winter, these seedlings are poised for rapid growth, and about the time my earlier crops are finished, the winter-sown ones are ready for harvest.

This article originally appeared in Kitchen Gardener #4 (August 1996).

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

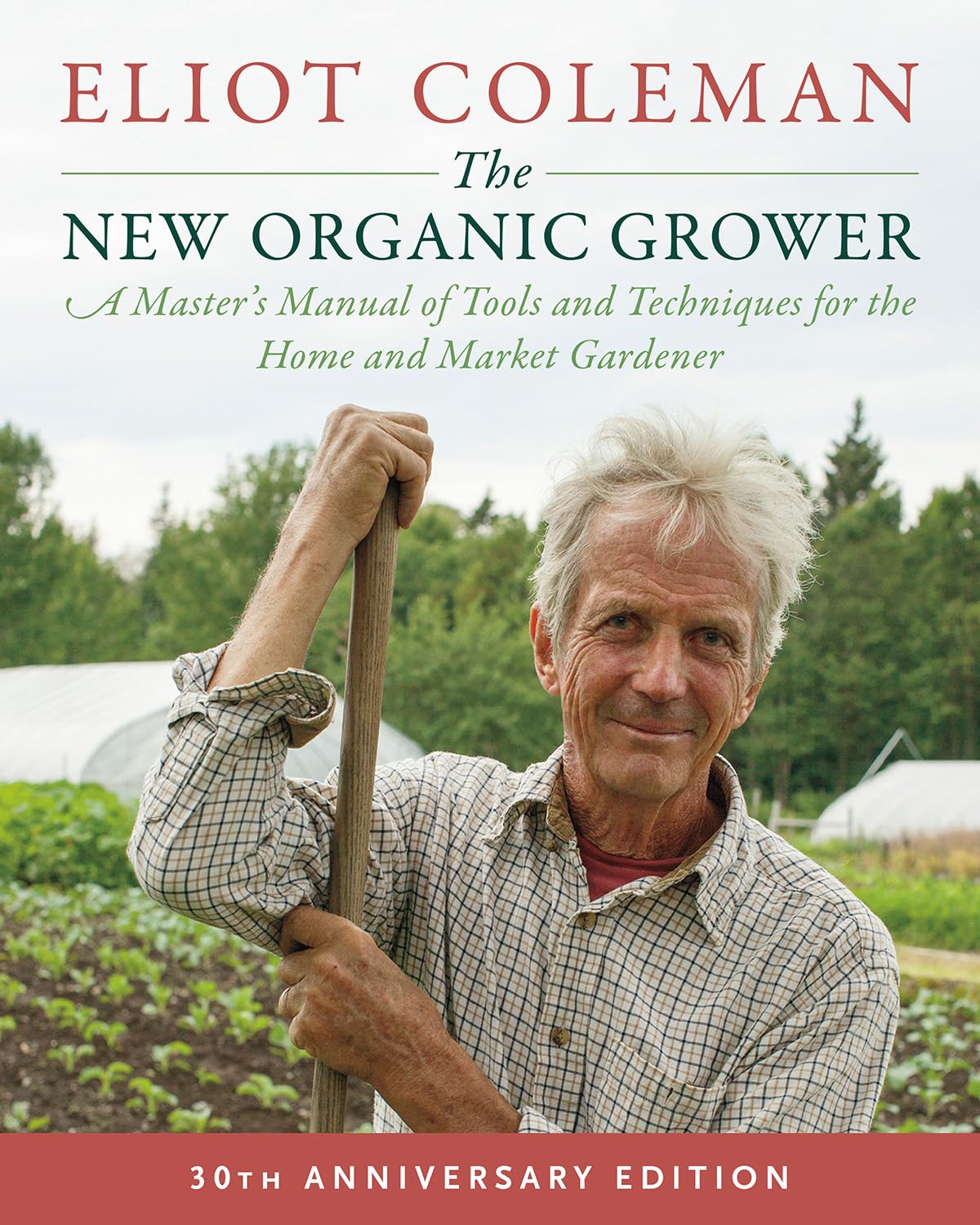

The New Organic Grower, 3rd Edition: A Master's Manual of Tools and Techniques for the Home and Market Gardener, 30th Anniversary Edition

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Ho-Mi Digger - Korean Triangle Blade

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Berry & Bird Rabbiting Spade, Trenching Shovel

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in