Growing Citrus in Pots

Gardeners with a sunny window and a little space can have fruit at their fingertips

Gardeners have been growing citrus in containers for thousands of years. Many of the first glasshouses, or orangeries, were constructed to grow oranges, lemons, and limes. But you don’t need a glasshouse or greenhouse—or to live in a tropical climate—to grow oranges, grapefruits, lemons, limes, or kumquats. The attractive and edible fruit combined with intensely sweet flowers make citrus a prized potted plant for any home. With a sunny window, proper container, good soilless potting mix, a bit of fertilizer, and a light hand at watering, you, too, can harvest these juicy treats.

Simple steps for a citrus harvest

1. Choose the right container

Although it is possible to grow citrus in nearly any type of container, we recommend a terra-cotta pot to control soil moisture. If you choose another type of container, it is essential that you water properly. If you select a plastic pot, for instance, be mindful that moisture will stay in the soil longer and that the roots will not dry as quickly. Citrus roots like to go dry between waterings; roots that are too moist, especially during cool weather, might lead to root rot, which generally leads to the death of the plant. Glazed ceramic containers also tend to retain moisture.

Citrus doesn’t mind being pot-bound; a pot-bound plant is one that has filled the pot with its roots and its foliage looks out of proportion with the pot. As citrus growers, we often choose to keep plants pot-bound; they are sometimes healthier and more productive in a small pot. We are cautious not to “overpot” (choose a pot that is too big for the size of the plant). That can lead to overwatering because there are not enough roots to take up the moisture.

2. Select a soilless mix

Citrus do not need fancy soil to thrive; a simple soilless mix with good drainage will suffice. We create our own mix of peat moss, perlite, vermiculite, and composted bark. The mix also includes limestone, which brings the pH to about 6.0—an ideal level for citrus.

3. Give your citrus sunlight

Citrus love—and require—lots of light. If you live in a cold climate and are growing citrus inside during winter, place your containers in a sunny south- or southwest-facing window for at least six hours a day. Bring the plants outdoors when temperatures reach a sustained 60°F to 65°F, and place them in full sun for at least half a day.

A little care goes a long way

1. Use a light hand when watering

As we mentioned, overwatering is the biggest threat to growing citrus. Most citrus benefit from growing in soil that is nearly dry between waterings. As a general rule, water only when the surface of the soilless mix appears dry or even when the plant shows a little wilting—that is, a slight curling of the soft new growth.

2. Fertilize sparingly

Citrus benefit from regular applications of a balanced fertilizer. That said, timing is everything: The general rule is to feed your citrus when it is actively growing and discontinue feeding during winter. We also recommend reducing or eliminating fertilizer as late summer approaches to allow growth—of roots and foliage—to harden off. As the days shorten in late fall, excessive nutrients can cause

weak or soft growth, especially in the root system, which leads to root disease. Feeding can resume once new growth is visible in late winter. Use an organic or a slow-release granular synthetic fertilizer. It is better to add small amounts of either to the water more often than to apply an occasional shot of a higher concentration. We use a quarter of the recommended amount once a week rather than the full concentration once a month.

Many citrus varieties are prone to iron chlorosis, which is a lightening of young leaves. This often happens during winter when growth is slow and temperatures are cool. We apply iron chelate as a foliar spray to correct this problem.

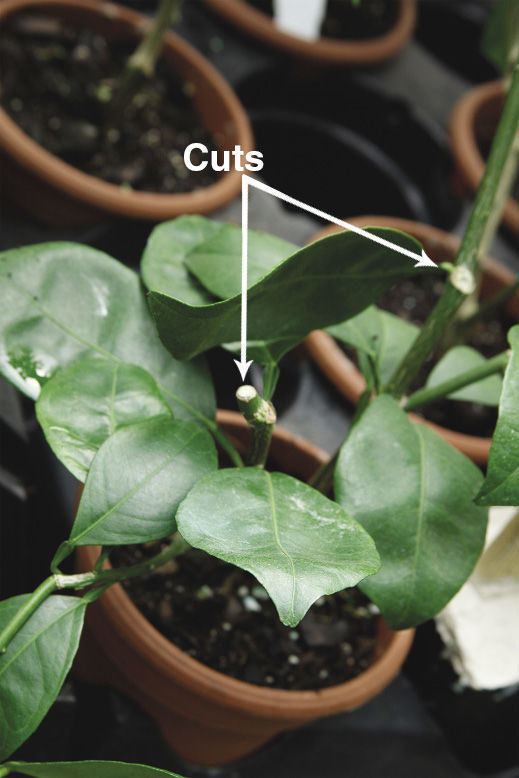

3. Prune only when necessary

Container citrus generally need only occasional pruning to help structure their form. A branch will often reach out or rise up, giving the plant an unsightly shape; this branch, also known as a lead, can be trimmed back. In addition, when plants are young, some strategic pruning can help create a full form as the plant matures. We recommend a multi-stemmed, sturdy plant that will bear heavy fruit. While you may thin fruit or stake branches, be careful not to diminish your crop by pruning too heavily. Keep in mind that the flower bud for next season’s crop often forms on the growth of last summer, and overpruning can diminish fruit production. For this reason, the best time to prune—if you prune at all—is right after the fruit is picked. In general, however, most plants are happy to be left alone and will produce fruit without a lot of attention.

4. Harvest when fruit changes color

Many citrus set bloom indoors during the cool months of late fall through winter and begin fruiting in late winter to early spring. Pick fruit any time after it has ripened—that is, when the green fruit changes color (unless it is a lime). Or if you prefer, leave citrus on the tree for ornamental appeal. Citrus not only provide a fresh supply of fruit at your fingertips but also make attractive houseplants, and many cultivars feature fragrant flowers.

Troubleshooting potential problems

Check roots if leaves are yellowing

Tap the plant out of its container to be sure that the roots are plump and white; if they’re brown and fall apart easily, they’re most likely dead.

If the roots appear healthy, give the plant more fertilizer. It is normal for plants that are grown cool—or even cold—to have yellow or light-colored leaves that drop. That will change once temperatures increase.

Search for pests and eradicate them

Scale insects, mealybugs, and spider mites are the most common pests of citrus. Scale insects appear as brown bumps and black sooty mold on leaves. Mealybugs usually form a cottony white mass at the base of leaf stems or on the underside of leaves, and black sooty mold may also appear on leaves. Spider mites, which cause light pinpricks on leaves, are sometimes a problem in hot, dry conditions. Check the underside of leaves with a magnifying glass. As spider-mite populations grow, plant webbing might occur. Persistence is the key to treating pests. For mealybugs, we recommend introducing a predator: the Australian lady beetle (Cryptaolaemus montrouzieri). The best treatment for spider mites is to blast the underside of leaves with cold water every day until they’re under control. You could also use Neem oil for all three pests.

A Few Favorite Fruits

Laurelynn Martin and Byron Martin are the owners of Logee’s Plants for Home and Garden in Danielson, Connecticut, and the authors of Growing Tasty Tropical Plants.

Photos, except where noted: courtesy of Logee’s Plants for Home and Garden

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

Razor-Back Potato/Refuse Hook

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Fiskars 28" Power-Lever Garden Bypass Lopper and Tree Trimmer

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Gardener's Log Book from NYBG

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in