How to Grow and Cook with Chervil

Delicate in flavor and pretty in leaf, this herb likes it cool

Chervil is not an herb that makes you sit up and take notice. It doesn’t force itself upon you, pushing its way around the culinary dance floor like a rosemary or a sage. It is, in fact, a shy, retiring sort of herb.

Learn more: Learn the Basics of Growing Basil

For a long time, chervil didn’t interest me. I couldn’t be bothered with this shrinking violet, which produced only sorry little wisps in my garden. But something spurred me to give chervil another chance, and I’m glad I did, for I wouldn’t want to be without it now.

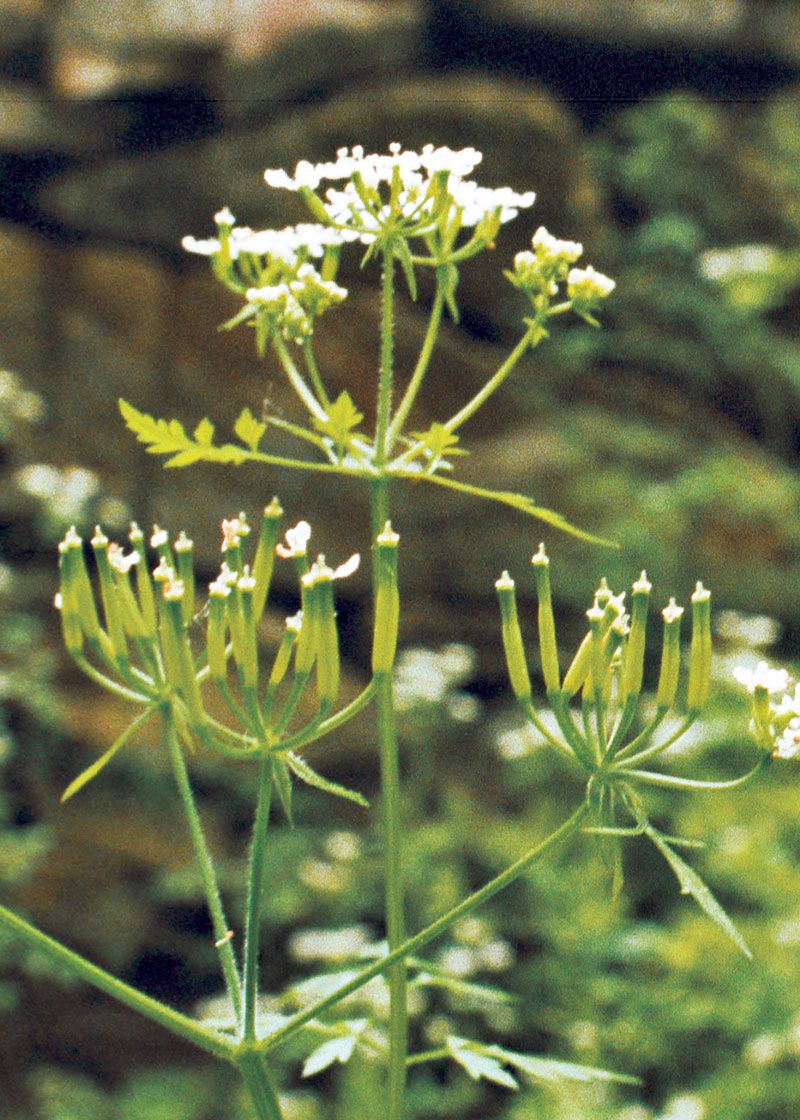

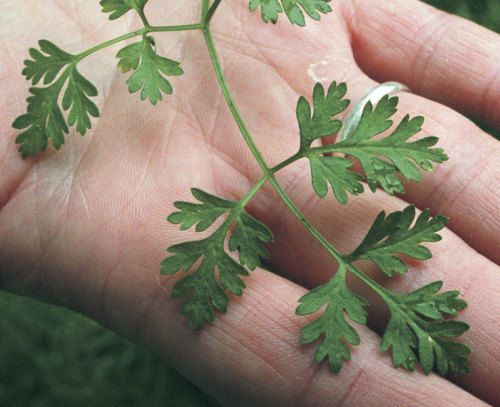

Chervil (Anthriscus cerefolium) is a hardy annual in the same family as parsley and carrot. It’s a pretty plant, with a growth habit much like parsley’s; however, chervil’s bright-green, flat leaves are cut along the edges, giving the plant a delicate, fringed look. The flavor of those leaves is equally delicate—an elusive, aniselike taste that dissipates with cooking. The plants grow to about 1 foot during their leaf stage but reach 2½ feet in flower.

Moist, fertile soil, and high shade suit chervil best

My best chervil crops have grown in rich, moisture-retentive soil and high shade or dappled sun. So many of the things growing in my kitchen garden require full sun all day that I’m thankful for any edible plant that thrives in the darker corners.

A month before planting time, I work aged manure and compost into the soil where I plan to sow chervil. This is one herb that must be direct-sown, because its fragile, taprooted seedlings won’t withstand transplanting. I broadcast the seed, rake it in, and water well.

I prefer to sow chervil thickly, scattering a packet’s worth in an area about 3 feet by 4 feet, and I don’t bother to thin the seedlings. Later, the crowded stems will help each other to stay upright, discourage weeds, and keep soil from splashing up on the leaves. That means I don’t have to wash the herb after harvesting, which is a real plus.

I sow chervil twice a year, around the typical last spring frost date (mid-April in Zone 6) and again in late August. Seeds from packets germinate in about two weeks; freshly harvested seed is a little quicker to sprout. Within a month I’m picking tender chervil leaves. My spring crop usually bolts at the first sign of summer heat. I harvest as long as I can from this patch, then let the plants flower. Like other members of the umbelliferous clan, chervil has flat, lacy flowers that attract beneficial insects.

Sometime in August there’s a crop of ripe chervil seed, looking just like caraway seed. To harvest the seed, I hold the cut stalks inside a large bowl or a paper bag and rub the seed heads. After harvesting the seed, I clear out the patch, dig over the soil, and resow in the same place. The second crop is usually much better than the first. The plants thrive in the cooler nights, and I have abundant harvests all fall. One year when I took the trouble to protect the plants during cold snaps, I harvested chervil almost until Christmas.

Plants sown in late summer overwinter in my garden, and I can harvest again from the same planting in early spring. Overwintered chervil tends to flower earlier than spring-sown plants, but sowing another spring crop in another spot each year keeps me in chervil for the longest possible time. During summer, when heat banishes chervil from my kitchen, I happily eat basil and other heat-loving herbs.

Harvest and use chervil just like you would parsley

Chervil is a cinch to harvest by pinching or cutting the stems. When grown densely, it rarely needs washing, but if your chervil seems gritty, swish it in cool water and lay it between the folds of a paper towel to dry. To store it, refrigerate the leafy stems in a plastic bag with a damp paper towel and they’ll keep nicely for a week or more.

In the kitchen I use minced chervil much like parsley, sprinkling it over dishes as a garnish, and adding it to vinaigrettes and sauces. I also add chervil sprigs to salads. I’ve grown mesclun mixtures that include chervil, but in my experience it doesn’t compete well with the other mesclun components. I much prefer growing it separately and adding it to a salad mix at harvest time. Cooked for longer than a few minutes, chervil loses its delicate flavor, so use it only as a last-minute addition.

Chervil is one of the four ingredients in fines herbes, the French mélange that also includes parsley, chives, and tarragon. To make your own, combine equal amounts of the quartet, minced. Use the herbs fresh to flavor vinaigrettes, omelets, softened cream cheese, herb butter, cooked carrots, chicken salad … The list goes on and on.

I use only fresh chervil. Dried chervil doesn’t retain much of its flavor. It’s also possible to freeze minced chervil in an ice-cube tray. Fill each cell with chervil, then top with water. To use the chervil, thaw it, let the water drain away, and add the leaves to a cooked dish just before serving.

This article originally appeared in Kitchen Gardener #24.

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

A.M. Leonard Deluxe Soil Knife & Leather Sheath Combo

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Chapin International 10509 Upside-Down Trigger Sprayer

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Razor-Back Potato/Refuse Hook

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in