How to Plan a Vegetable Garden

Grow more fruits, vegetables, and herbs by devoting a few hours each winter to planning

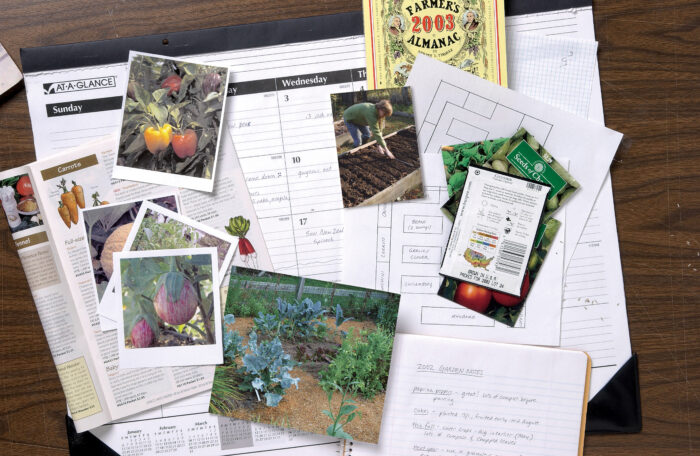

No one can dispute that good soil, plenty of nutrients, and adequate water are important to the success of a vegetable garden. But there are other things you can do to become a better gardener, like making a map of your garden, getting to know your local climate and the varieties that grow well there, and keeping track of the season on a calendar. By devoting a few hours each winter to planning and a few minutes each day during the season to record-keeping, you can increase your yields and set yourself up for success in future years.

Put garden plans on paper

I wish it hadn’t taken me so long to get around to making a scale drawing of my vegetable garden. Twenty minutes spent with pencil, paper, and a ruler several years ago continues to pay big dividends, both when I’m figuring out a planting scheme and when I’m calculating how much fertilizer or soil amendment to add. Graph paper makes it easy to draw the beds to scale, but I find that all those squares get in the way later when I’m making notes on my drawing. So instead, I make my first drawing on graph paper, using a dark, heavy pen. Then I lay plain paper over the graph paper, trace the outline of the beds, and note the square footage of each bed in the margins. This second drawing is my master plan. I make photocopies of it and use the copies for sketching planting plans and making notes.

I have one planning session in late winter when I draw up the map I will use as my planting plan. Because things don’t always go according to plan, I have another planning session in late summer. At this time, I update the map so that I have an accurate reflection of my current year’s garden. I date my garden plans and keep them from year to year so I don’t have to rely on my memory of what I planted where.

Once I’ve updated my current season’s map, I start planning for the following year. I spread out the last four or five years’ worth of plans and study where I grew what. They help me figure out where to rotate the solanaceous crops (tomatoes, peppers, and eggplants), the alliums (garlic and onions), the cucurbits (cucumbers and squash), and basil, which need to be planted in different beds each year because they are sensitive to soil-borne diseases and pests.

How to succeed with succession plantings

Succession planting—growing two or more crops in the same space back to back—will greatly boost a garden’s overall yield. Most parts of my garden in southern Connecticut can grow two crops a year, even three if I’m ambitious and stay on top of things. To succeed at succession planting, it is critical to have a plan and a schedule and to know the length of the growing season.

When planning successions, I categorize vegetables into cool-season quick crops, long-season crops, warm-season quick crops, and crops that overwinter. Instead of leaving the soil bare, I use cover crops to fill gaps in the schedule when I can’t get a harvest, sowing buckwheat in summer and clover in fall. With my 195-day growing season, I can easily get a quick crop, like radishes, in and out before planting a long-season crop, like peppers. I can also separate spring and fall lettuce plantings with a round of buckwheat or follow the July garlic harvest with a planting of late beans or cucumbers.

Cool-season quick crops

Arugula, broccoli rabe, lettuce, radishes, spinach

Long-season crops

Leeks, onions, peppers, tomatoes

Warm-season quick crops

Bush beans, cucumbers, summer squash, zucchini

Crops that overwinter

Cabbage, garlic, kale, leeks, spinach

Determine your growing season

For the most part, my garden is an escape from things like math, but I couldn’t garden as well as I do without knowing my frost-free dates, the length of my growing season, and the number of days to maturity of the vegetables I grow. These numbers are important cues to when to plant and when to harvest.

The dates of the last frost in the spring and the first frost in the fall are critical when figuring out the timing of long-season crops like pumpkins and winter squash and are particularly important when squeezing in a late planting of a quick-maturing crop. The number of days between the last frost and first frost in a region is the length of the growing season. In southern Connecticut, mine is 195 days. An almanac, the local extension service, or the internet is a good place to find these dates. Remember that frost-free dates are not cast in stone; they are simply averages.

I use my frost-free dates along with the number of days to maturity listed in a catalog or on a seed packet for a given variety to determine when and what to plant. The days-to-maturity number indicates how long it will take a plant to produce something harvestable, counting from the day of germination for direct-seeded crops, or from the day of transplanting for crops started indoors. As with frost-free dates, the number of days to maturity is a guideline, because it will vary depending on regional climates and growing conditions. For example, if warm-season crops are planted before the soil and the air is adequately warm, they’ll take longer than normal to bear fruit. Likewise, if they are planted later than normal when summer is in full swing, they’ll mature earlier than the listed time. A cool summer slows things down; a hot one speeds them up. Last summer, which was unusually warm, I planted a 60-day cucumber variety on July 1. The seeds germinated in less than 48 hours, and I was picking cukes just 42 days later.

A calendar helps you stick to the plan

The third prong in my garden-planning strategy is my garden calendar. Every year I get a flat desk-pad calendar and use it to schedule sowing and transplanting tasks. (A wall calendar works, too, provided each day’s space is large enough for notes.) When my seeds arrive, I sit down with the calendar, my planting plan, the seed catalog, and the seed packets and make notes about when to start what indoors, when to transplant, and when to direct-sow other seeds. For example, I will note to plant the cucumber variety ‘Amira’ on June 1. About 55 days after it germinates I’ll expect to see the first fruit. Since cucumbers produce well for three or four weeks, then start to succumb to powdery mildew, I’ll make a note on the calendar in mid-August to tear out the cucumber vines and plant a fall crop of carrots.

I’ve learned to block out any planned absences on the calendar, like vacations, so I can schedule around them. During the growing season, I make notes on the calendar about rainfall data, when I start and finish harvesting a crop, and other significant events, like weather extremes. I’ve also learned to keep the calendar handy, because if it’s out of sight it doesn’t work. Of course, I never do everything that’s on the calendar, but it helps remind me to do things on time and is a useful tool when I am planning the next season’s garden.

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

Nesco Snackmaster Express Food Dehydrator

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in