Growing Blueberries

This attractive shrub and delicious superfood is easy to grow if you follow these steps

Up at dawn and to bed at dusk, I spent my childhood summers working on the family blueberry farm. On our 200-acre spread in the lakes region of New Hampshire, my brothers and I would camp in the fields, care for the wild blueberries, then help harvest them. Of course, the best part was eating the blueberries.

The wild blueberry is still my favorite fruit, which is due, I’m sure, to the quantities I ate during summers at the farm. The wild lowbush blueberry, though, is difficult to transplant and, therefore, difficult to grow outside its native habitat, the Northeast. The solution for blueberry lovers is to grow highbush blueberries. Highbush varieties are easily grown in nurseries and easily transplanted into gardens. They also form attractive bushes and yield large, easy-to-pick fruit. They’re a beautiful and tasty addition to your edible landscape.

Get the most from your blueberries

|

Choose a plant-based on your climate

Blueberries are generally hardy to about –20°F, but the temperature isn’t the only consideration. Blueberry plants also have a winter-chilling requirement to ensure they become dormant and remain so for a long-enough period. The requirement is measured in hours and varies depending on the variety. Most blueberry plants must have many hours of cold—some require 1,000 or more. Choose your varieties according to the number of winter hours below 45°F in your area.

When you buy plants, be sure to get two or more varieties because cross-pollination of flowers improves crop size. Highbush plants so named because of their height (5 to 6 feet tall) and their upright stance are the most widely grown blueberries. They are the best choice for gardens from the Mid-Atlantic north, where winter temperatures fulfill the blueberry’s need for long chilling. But some highbush varieties are adapted for warm-weather climates, with shorter chilling requirements met by less severe winters.

You can buy blueberry plants either bareroot or container-grown. While bareroot plants perform well if you plant them in early spring and keep them well watered, I think the container-grown stock is more forgiving. You can plant it with a good chance of success almost any time the ground is not frozen. Your local nursery should have the varieties with the correct chilling requirement for your area. My favorites here in New Hampshire are ‘Berkeley’, which has big, sweet berries, and ‘Blueray’, which offers both large fruit and a large crop.

Provide a low pH and plenty of space

Blueberries thrive in very acidic soil, as do other members of their family, including rhododendrons and azaleas. In fact, they require a pH of between 4.5 and 5.2. If your soil pH is too high, plants are likely to grow poorly and exhibit symptoms of iron deficiency. The leaves of blueberry plants short of iron turn yellow between leaf veins, signaling a condition known as iron chlorosis. While this can be corrected with foliar applications of iron-containing fertilizers, such as iron chelate, this is a temporary fix at best.

The old adage “Don’t guess—soil test” applies here. If your soil pH is too high, it can be lowered a few different ways. An application of fine ground sulfur or aluminum sulfate will do the trick. The rates will vary, but in general an application of 2 to 3 ounces of fine ground sulfur per bush will do the job of acidifying sweet soils. Spread the sulfur evenly over a 4-foot-square area around the plant. For new plantings, spade or till the sulfur into the soil before planting. While sulfur is the preferred additive, you may have better luck finding aluminum sulfate. If you use aluminum sulfate instead of sulfur, you will need about six times as much material to do the job.

Don’t confuse aluminum sulfate with the fertilizer ammonium sulfate, which contains 21% nitrogen and can be used as a fertilizer for blueberries and other acid-loving plants. Sulfur and aluminum sulfate are not fertilizers, and they should be applied only if a soil test indicates need.

If you live in northern regions, you should plant in early spring after the risk of a severe freeze has passed. If your garden is in a more moderate climate, however, you can plant in either spring or autumn.

Space highbush plants 5 to 6 feet apart so that the sun can get to all sides of the bushes. If you’re using them as a hedge, plant them only 3 feet apart. Set the blueberry plants at the same depth they were planted in at the nursery. Firm the backfill soil around the plants. Water the plants well, and let the water soak in before putting the last inch or so of soil back in the hole.

I consider mulch essential for blueberries. A 3- to 4-inch-deep layer of organic mulch extending about 2 feet in all directions from the crown will improve the soil’s moisture retention, allowing its shallow root system access to a consistent supply of water. Make sure the mulch is level with the ground rather than mounded so that water will

penetrate it with no roll-off.

Raise the Acid Level—Fast!

Blueberry plants grow—and thrive—from northern Maine to southern California. But they have a specific need for highly acidic soil. If your soil acidity is not correct, your plants will quickly die. For alkaline soils that are too sweet, I recommend amending your planting area with peat moss. Peat moss increases the acidity quickly and also helps meet other blueberry needs, such as moisture retention.

You can use sulfur if you’re willing to wait. It will typically take at least a year for this amendment to have any effect on your soil’s acidity. The same is true in using pine-needle mulch. The acidity increases only a small amount—if at all—as the pine needles break down. Instead, make a planting hole at least twice as wide and as deep as the container your blueberry plant comes in. Backfill the hole with moist peat moss, and your family will enjoy picking fresh blueberries every Fourth of July.

—Matt Waters and his family raise more than 20,000 blueberry bushes at Waters Blueberry Farm in Smithville, Missouri.

Feed the berries, not the birds

I think the best fertilizer for blueberries is one of the specialty foods for acid-loving plants, usually rated as 7-7-7. It is often sold as fertilizer for rhododendrons and azaleas. Feed each newly set plant with an ounce or two of fertilizer two to three weeks after planting. Be sure to weigh the fertilizer; any more than this amount could injure or kill the plant. I prefer to apply fertilizer in a circle 18 inches from the plant’s crown, just to be safe.

The only truly effective weapon in the battle with the birds is netting. Most garden centers sell lightweight, plastic netting for this purpose. It’s expensive, but if it’s stored under cover when not in use, it will easily last 10 years. Place the netting over the bushes as soon as the first fruit turns blue, and leave it in place, except for harvesting, until the crop is finished or you’re ready to share with the birds. Be sure the enclosure is complete and goes all the way to the ground. You can secure it with U-shaped wire pins or by placing stones or other weights on the tails of the netting.

Mummy berry disease can be a serious problem, especially if your plants are in an area where they don’t dry quickly after rain and a substantial wild-blueberry population grows nearby. Infected fruit will shrivel and drop just before ripening, overwintering as “mummies” to start new infections the following spring.

If you have a mummy-berry problem, pick off and destroy or bury infected fruit as soon as you notice them. The application of a new 2-inch-deep layer of mulch in the autumn will cover those that you missed, preventing disease spread the next spring.

Blueberry maggot is another major pest. Infested berries are soft to the touch. Sticky red spheres (sold in garden centers and catalogs for control of the apple maggot) can be used to combat this pest. As soon as your fruit begins to redden, hang these sticky spheres close to the outer edge of the foliage in the upper half of plants. They attract and capture the adult maggot flies before they lay eggs in your fruit.

People sometimes complain that cultivated blueberries aren’t as sweet as wild ones. I think the problem is that blueberries turn blue a week or more before they’re sweet. A good way to tell if blueberry is ready to eat is to harvest some berries and look at the ring of skin around the stem scar. If this ring is reddish, the fruit is apt to be tart. But if the ring is bluish-black, like the rest of the fruit, get ready for a real treat.

Blueberry Pruning 101

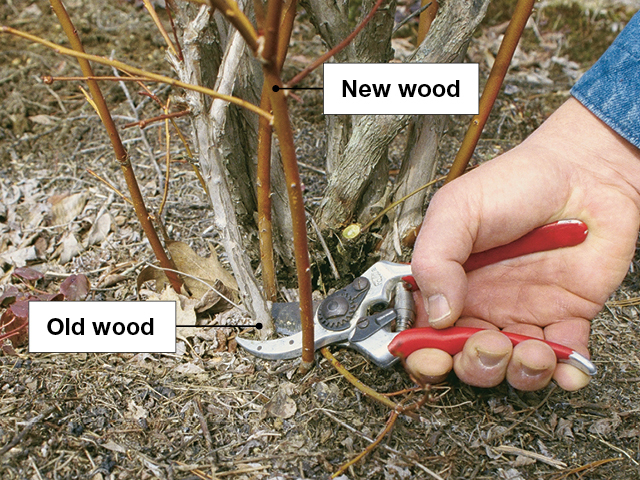

Pruning blueberry plants isn’t difficult if you let the plant tell you what to do. Blueberry plants produce fruit on one-year-old wood. This productive wood is smooth and either reddish or yellow in color. Older, nonproductive wood, in contrast, will be rough-skinned and gray, with few—if any—large flower buds.

Start by identifying the weaker gray wood and the young, productive wood at the base of your bush.

Remove at ground level one to three of the oldest large gray canes. Prune lightly every year in late winter or early spring.

William Lord spends his summers as a plant biologist at the University of New Hampshire.

Photos, except where noted: Frank Clarkson

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

Corona E-Grip Trowel

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Razor-Back Potato/Refuse Hook

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

ARS Telescoping Long Reach Pruner

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

I purchased 3 patio blueberry bushes this spring through a mail order company. They were small and are growing well. I know the soil has to be acidic and that seems to be fine. Does anyone know if I will get fruit this fall? They are in large pots. I am planning on overwintering them in my hobby greenhouse where they will chill off as all bushes need to but because they are in pots, I want to protect them, from freezing. I live in Pittsburgh, PA where we had a long late freeze this year. Would appreciate any advice or tips on growing these. Thanks all! (Love this site! I never before wrote on a garden site and hope to enjoy this for a long time!)

There is a Longmont, Colorado man whom you can find online. I have a producing berry that I planted in a peatmoss bale. It usually harvests in the June/July range. I must take great care to keep my peat bale separate from the alkaline soil here in the Rocky Mountain west. I check pH regularly because even my water is alkaline-meaning to water I use a liquid iron-acid fortifier from the nursery. If you have more acid soil you will suffer less plant stress. Using a peat bale might be your best bet for preventing the frozen roots as well, but they bury these bales instead of green housing them. To protect the bushes themselves from flash freezing, I wrap them up as directed in the Longmont films.

I live in Longmont, I've tried to plant blueberries and have failed, never gotten a single berry.who is this Longmont man?

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in