Inspired Design: What Are the Basic Elements of a Garden?

Explore the fundamentals that take a landscape from good to great

Perhaps one of the most fundamental questions in landscape design is, after all, What is a garden? What are the basic elements of a garden? Most people would immediately answer: an area devoted to plants. Indeed, the first definition in Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary is “a plot of ground where herbs, fruits, flowers, or vegetables are cultivated.” With all due respect, I’d like to offer a broader definition.

Learn more: Elements of a Japanese Garden, Elements of a Cottage Garden

The Garden Defined

For me, a garden is a place—planted or not—that is set apart by some type of enclosure and whose elements have been arranged according to certain principles: either natural, functional, horticultural, architectural, philosophical, or aesthetic. That’s a long definition for what might seem like an obvious concept. To get to it, I thought about many different kinds of gardens and the conditions they represent.

Obviously, a vegetable patch is the most basic kind of garden—a plot of land set aside to create the best growing conditions for the chosen plants. With the many critters around eager to munch, most of us enclose our gardens and orchards with fences. We sow our seeds in careful rows, culling out the weak to favor the strong. In other words, we set out our plants in an unnatural way to encourage them to produce in abundance.

A terrarium is also a kind of garden, although miniature in scale. With its glass-walled enclosure, which offers plants a humid and temperate environment, it also allows its viewers a glimpse into an intimate world suggesting the vastness of nature while using the tiniest of plant species. We delight in this scale change and ask ourselves, “Are we minute or mammoth in relation to this garden?”

The cemetery plots I’ve designed qualify as gardens because they are enclosed (by walls, hedges, landform, or ornamental iron fencing) and created as contemplative memorials to the loved ones interred there. Carefully arranged with places to sit (benches or natural perch stones), focal points (memorial stones, special trees, sculptures, or distant views), and beautiful plantings, these commemorative gardens offer their visitors a place set apart for memory.

By my definition, the courtyards of Spain and Morocco are gardens, with their elaborately tiled floors, walls, and archways surrounding a central fountain, despite their dearth of plantings. Created as urban oases of quiet and coolness, they are organized according to architectural principles, with pots placed at corners, around circles, or at the base of columns.

I would even go so far as to call a glade in a forest a garden, with its enclosure of trees and its design provided by the hand of nature. After all, it is nature’s hand that we seek to recreate in the curves and meanders of our own backyard compositions, never quite succeeding as simply and gracefully as nature does through her own principles of design.

I tried to recreate the principles of musical order in the Toronto Music Garden, a public park composed of six garden spaces designed as an interpretation of the First Cello Suite of J. S. Bach. I listened again and again to its prelude and five dance movements and came up with a design that suggests the shapes of clefs, lyres, notes, and cellos as it curves and twirls throughout its three acres along Toronto’s Harbourfront.

When I lead garden design workshops, my favorite exercise is to ask participants to create a “garden” on their lunch tables, using their leftovers, the contents of their purses or briefcases, and even clothing items. Working in groups with only 10 minutes to complete the exercise, everyone always comes up with remarkably thoughtful, elegant, and often riotous “landscapes” from the materials at hand. These compositions show that we all have an innate sense of design and that we shouldn’t be afraid to create beauty with whatever materials are available. To me, this freedom to be playful is an important part of the creative process.

To create a garden is to designate a place as special. The best ones create a sense of emotion in space. They can evoke peace, melancholy, delight, wildness, joy, or any other mood. Regardless of your gardening experience, the simple intention to make a space into a garden is a powerful first step. Staying open to whatever form that garden might take is part of the thrill of the design process.

—Julie Moir Messervy is the author of three books, including The Inward Garden: Creating a Place of Beauty and Meaning. She designs private and public gardens and lectures about landscape design. This article first appeared in Fine Gardening #88 as “How Does a Space Become a Garden?”

More inspired design:

The Value of Voluptuous Curves

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

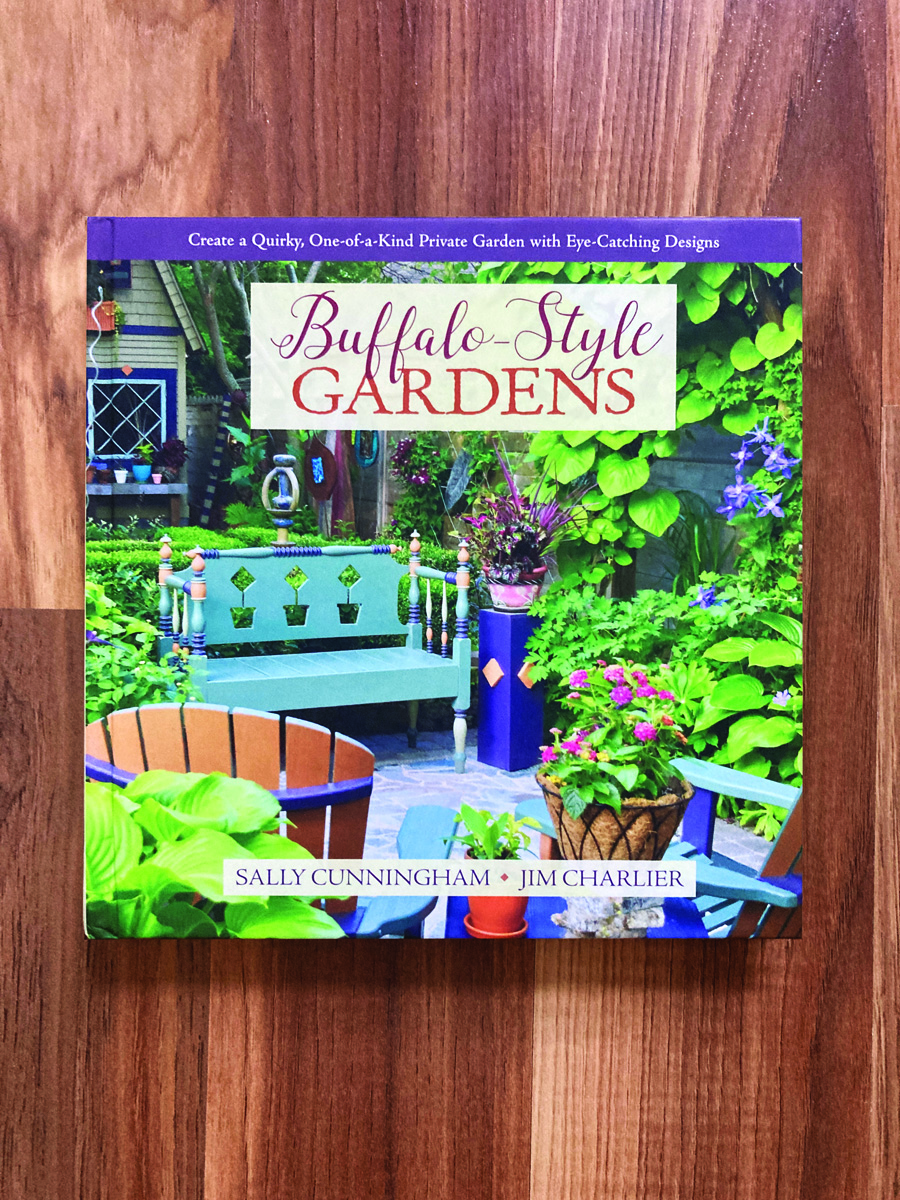

Buffalo-Style Gardens: Create a Quirky, One-of-a-Kind Private Garden with Eye-Catching Designs

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

A.M. Leonard Deluxe Soil Knife & Leather Sheath Combo

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

it's really fantastic

geat design

great

wonderful

mesmeric

graceful

marvelous

nice

marvelous

Really beautiful!

I like it!

marvelous!

so beautiful

Very Nice!

interesting

Amazing!

Wow-what a garden! excellent

Wow it's amazing!

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in