The Science of Pruning

When and where you do it can mean the difference between a happy plant and a dead plant—but why?

Pruning is a pretty darned big, and sometimes complicated, topic. Even narrowing it down to the science part and leaving out the artsy stuff still leaves a lot to learn. The first thing a would-be pruner needs to know is that plants, by and large, are resilient. Most people new to pruning are afraid that they’ll cut the wrong branch and end up killing their favorite tree. It’s true that a few ill-placed pruning cuts can make for an ugly specimen or result in a structurally unstable tree. But it’s highly unlikely that a few errant cuts will kill your subject.

Of all the bits and pieces that go into developing a sound pruning strategy, the most important is having an understanding of how a plant will (or at least will likely) respond to pruning. A basic knowledge of a few core principles can help you do a fairly good job of predicting plant response and, in turn, do a fairly good job of pruning.

Energy balance drives the pruning plan

The most frequent question asked about pruning is “When should you do it?” The traditional recommendation is to prune a flowering plant depending on when the plant flowers. If it flowers on old wood (growth from the previous season), prune after flowering to avoid cutting off spring blooms before you have a chance to enjoy them. But if the plant in question flowers on new wood (the current season’s growth), prune in late winter.

While this is sound advice to ensure maximum flower enjoyment during a single season, it completely ignores the physiology of the plant. Rather than obsess about a few blooms in one season, it’s better to consider the overall energy balance of the plant.

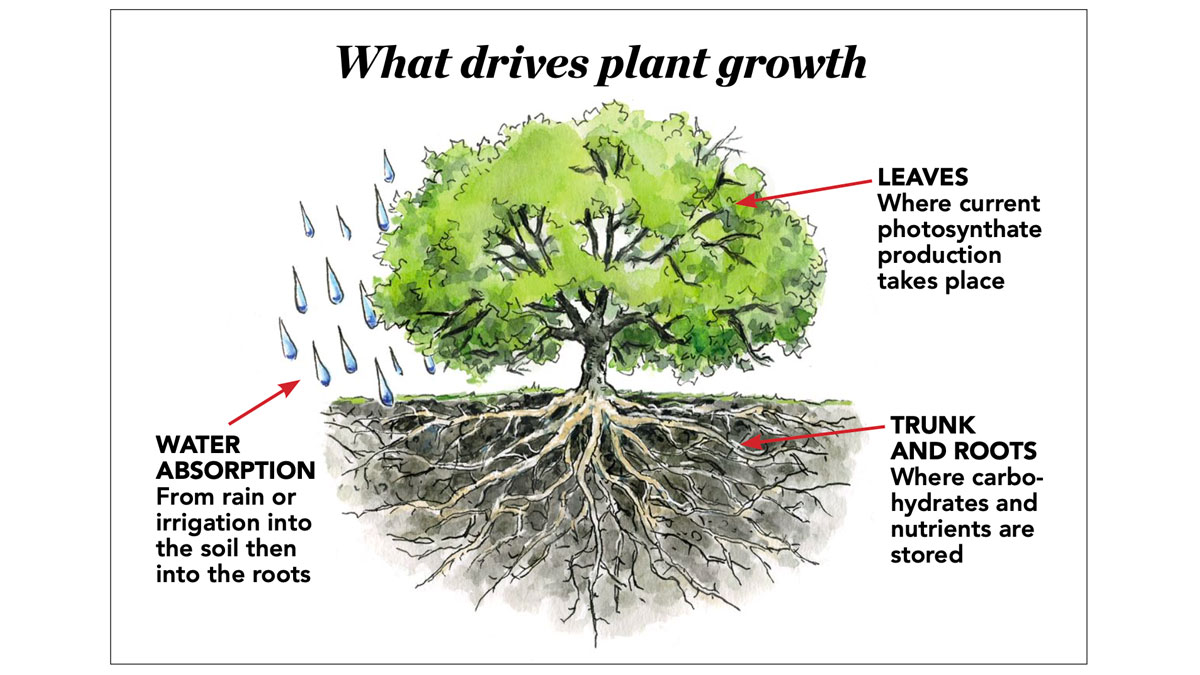

The engines that drive plant growth and vigor are (1) carbohydrates and nutrients mobilized from stored reserves, (2) current photosynthate production, and (3) water absorption (see illustration below). The first two engines fuel production of new plant tissue (they build new cells), while the third drives cell expansion and shoot elongation. The energy balance in a plant is set by the size of the engine(s) divided by the quantity of growing points that will use those energy resources.

A plant’s energy balance governs the vigor of the plant’s response to major pruning. In otherwise healthy plants, pruning in the dormant season is invigorating to the plant, while pruning in the late spring and summer results in reduced vigor (see “Pruning outcomes depend on energy,” below).

Pruning outcomes depend on energy

The old adage “Prune when the shears are sharp” is often followed by “and when the plant is sleeping.” While making a few minor cuts here and there at any time of year is fine, more major pruning needs to be timed according to a plant’s energy balance.

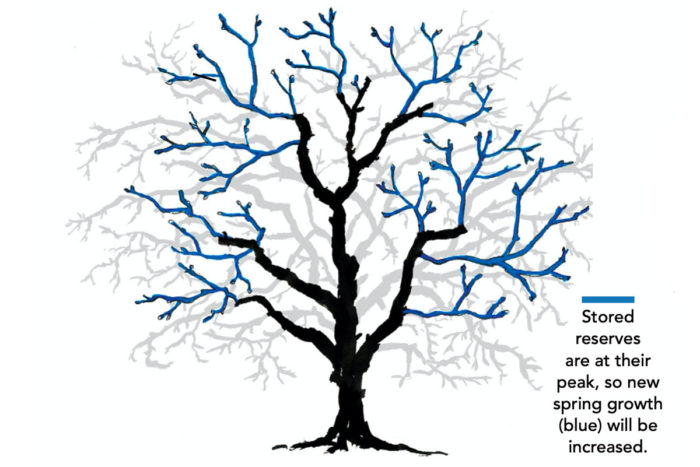

Late winter pruning spurs lots of new growth

Take a healthy apple tree that’s been ignored for years—one that’s filled with crossing and rubbing branches, weak branch angles, and too dense a crown for its own good. A major winter thinning of the tree allows most of the stored reserves to remain intact (reserves are stored in roots, the crown, and the main trunk) but drastically reduces the number of growing points that will use those stored reserves to fuel growth the following spring. The result is more-vigorous spring growth from those remaining growing points. Think of winter pruning like holding your thumb over the end of a garden hose. With the same amount of pressure, but a reduced opening, you get a much more forceful spray.

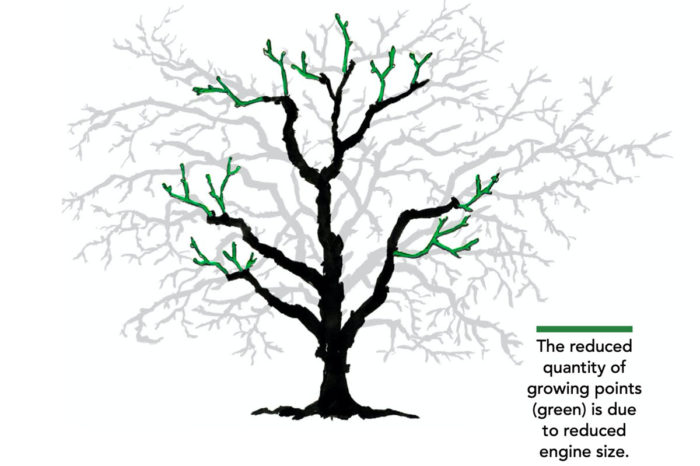

Late spring pruning limits new growth

Take that same apple tree and wait until late spring to do the same pruning, and you have a completely different story. With this timing, the plant will have used up its stored reserves and you will have gone in and reduced the photosynthate engine (the leaf area) that would fuel recovery and regrowth. You’ve reduced the quantity of growing points, but you’ve also reduced the size of the engine. The result is not a whole lot of regrowth after pruning. So you need to decide what response you want to encourage in your plant and then use the plant’s energy balance to choose your timing.

Timing plays a critical role in cold tolerance

Two detrimental things can happen if the timing of your pruning is off (done in late summer or early winter): induced loss of cold tolerance and late-season pruning-induced regrowth that has insufficient time to harden off before winter. For example, it’s the middle of August and you’ve just realized that you never got around to shearing your boxwood hedge. Now it looks like an uncoiffed Old English sheepdog. You drag out the electric shears and turn all your boxwoods into perfect Platonic solids. The problem is, there’s probably still plenty of warmth left in the season to encourage a nice crop of soft, fluffy new growth, but there’s not enough time for that growth to harden off before winter sets in. The result is likely to be the easily recognizable shaggy brown top that shows up later in winter from shoots damaged by the onset of cold temperatures.

Another problem can occur even if you wait to prune in winter, as many books advise. Research has shown that the energizing impact of heavy pruning can drastically reduce the low-temperature tolerance of the remaining plant tissue, even when pruning is done well into winter. You may notice blackening of the tissues around the pruning wound. This loss of cold tolerance occurs even though the plant hasn’t yet put out any new growth. Of course, this is particularly problematic if the plant is already somewhat marginal in your garden’s climate. So if you’re growing a Zone 7 hedge in Zone 6, you might want to wait until late winter to do that heavy shearing, after the threat of extreme low temperatures has passed.

Hormones dictate plant response

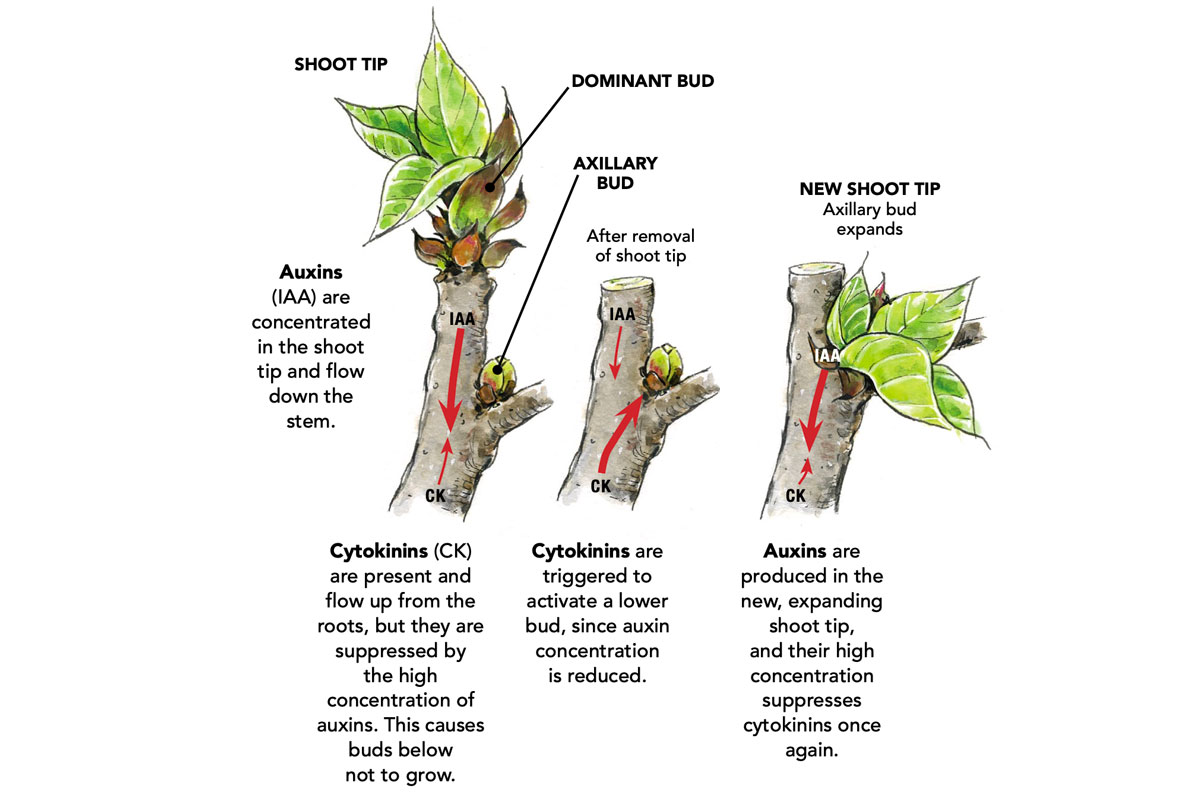

Plant hormone levels play a major role in a plant’s response to pruning. Auxins are key plant hormones that are produced in expanding shoot tips and move down the stem. The higher concentrations closest to the tip tend to suppress the opening of buds below. This is called apical dominance and serves a valuable purpose in promoting the growth of the shoot tip at the expense of the growing points located lower down the stem. If a plant is competing for sunlight with its neighbors, it is much better to have a few strong shoots reaching for the sky than a thousand shoots competing for limited nutritional resources within the plant. However, when you prune and remove a growing tip, you remove the source of the bud-break-suppressing auxin, allowing the lower bud(s) to break and grow (see “How apical dominance works,” below).

How apical dominance works

Another group of plant hormones, cytokinins, are produced in the young, growing roots and then move up into the shoots, where they work to stimulate bud break. The currently accepted hypothesis is that auxins suppress the action of cytokinins. Remove the auxin, and the cytokinin can do its thing. That’s the science behind growers using cytokinin sprays to induce more lateral branching and bushier plants. The sprays increase the ratio of cytokinin to auxin, allowing buds to break and grow. There are even “chemical pinching” sprays that enhance lateral branching by killing the rapidly growing shoot tip—just as if you had pinched out the shoot tip with your fingers.

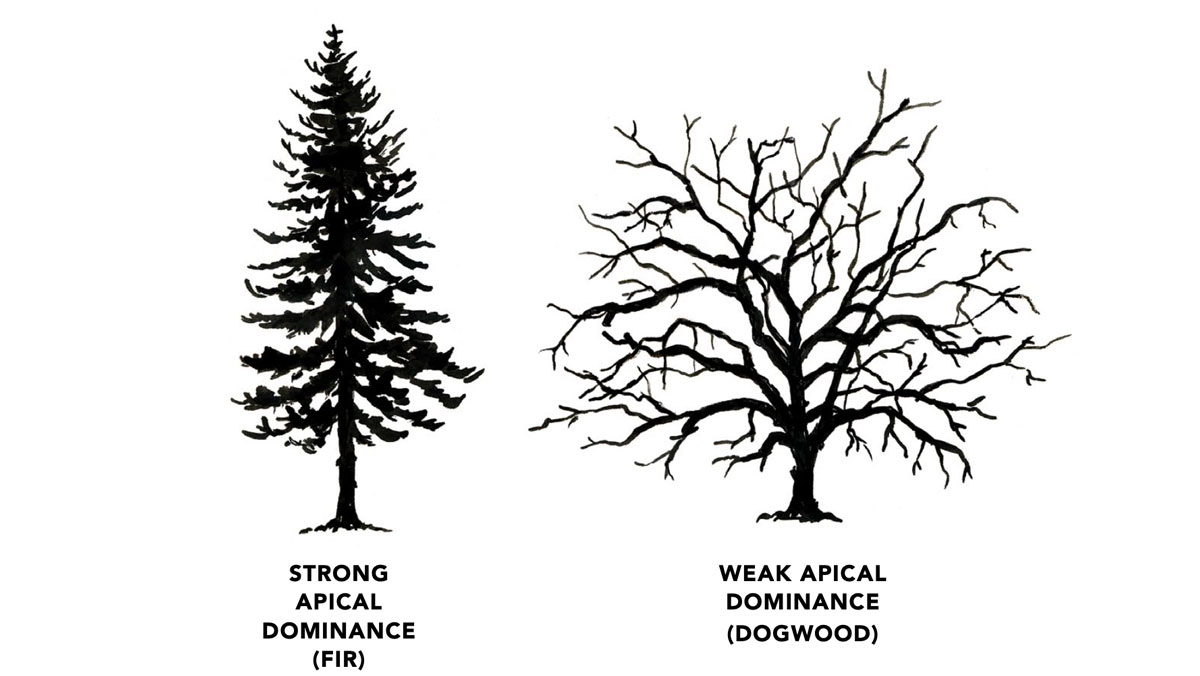

The strength of this apical dominance contributes significantly to a plant’s characteristic shape (see “Hormones affect habit,” below). Strong apical dominance yields a single-leader growth type and narrow conical shape—think bald cypress (Taxodium distichum, Zones 4–9) and balsam fir (Abies balsamea, Zones 3–6). Weak apical dominance yields more diffuse branching, such as that seen in flowering dogwood (Cornus florida, Zones 5–9) and golden rain tree (Koelreuteria paniculata, Zones 5–9).

Hormones affect habit

Healing is both immediate and delayed

No matter how well we plan, there’s no getting around the fact that all pruning results in mechanical injury to the plant. When injured, plants have both immediate and delayed responses. The immediate response involves a mind-numbing cascade of signals being bounced around the plant to activate genes related to production of defense compounds—all designed to reduce the ability of pathogens to gain a foothold in the new, open wound. What takes a much longer time is for pruning wounds on woody plants to heal over completely. This occurs with the slow development of tissue that forms around the perimeter of a pruning cut. As gardeners, our task is to ensure that we do all we can to minimize the injury-related threat to the plant. The best way to do that is by encouraging the wound to heal as quickly as possible with a proper cut.

First, keep your pruning cuts as small as possible. With young trees, if you keep your cuts to under ¾ inch, generally they will heal in a single growing season. This is easy to do in a perfect world, but it’s hard to do when planning corrective pruning on an older plant.

Next, plan to prune when the tree is most active in trunk development—spring and fall. Wound closure and healing are accomplished by the cambium layer (that ultrathin layer of live cells just below the protective, outer bark), and spring and fall are the two times of the year that cambial activity is at its peak. One reason so much tree pruning is done in winter is because, with the leaves gone, arborists can actually see what they are doing. Of course, there is also little in the way of pathogen attack going on in the depth of winter.

Finally, make a smooth cut in the right place, since smooth cuts heal much faster than rough or jagged cuts. Understanding the science behind pruning can help you become a better pruner, with an even better garden.

Paul Cappiello is executive director of Yew Dell Botanical Gardens in Crestwood, Kentucky.

Fine Gardening Recommended Products

ARS Telescoping Long Reach Pruner

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

CobraHead® Long Handle Weeder & Cultivator Garden Tool

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Pruning Simplified: A Step-by-Step Guide to 50 Popular Trees and Shrubs

Fine Gardening receives a commission for items purchased through links on this site, including Amazon Associates and other affiliate advertising programs.

Comments

I am already a subscriber to Fine Gardening and I can’t access the content without subscribing again and paying more money! There is no option for current subscribers!

@springle We don't have an option to view our new articles via our website for subscribers, but this is a feature we are currently working on providing! This preview article is to show our online audience what is new in the magazine.

Your print subscription does come with a digital subscription, however. To read our magazine in a digital format, please download the Fine Gardening app on your phone or tablet and login.

You can reach out to our customer service department if you would like specific instructions for how to access our digital issues at customerservice@finegardening.com.

Thank you and sorry for any confusion!

The Science of Pruning was a very informative, well written and in-depth article. This is the kind of garden article I am looking for when I joined All Access. Thank you,

Flwr Grl

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in